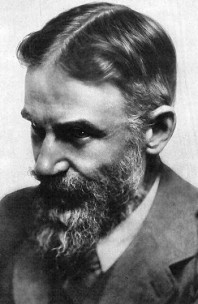

The literary intelligensia of the early twentieth century responded in various ways to the appearance of moving pictures. George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950), more than most, responded with words. All writers depend on words, but Shaw’s reputation in particular was based on words in profusion. He loved to talk, the characters in his plays love to talk and talk, and his writings in every other form beyond the theatre were all part of an unstoppable conversation the man was compelled to have with his times. So what possible interest could there be for him in the silent film?

When the first motion pictures were projected in Britain in 1896, Shaw was already renowned as a critic and a playwright, and into the new century gained increasing stature as a public figure whose opinion on everything was sought and enthusiastically given. His plays and the long prefaces he wrote for their printed versions became vehicles for his opinions on artistic, social and political matters.

It is no surprise, therefore, that Shaw had views on the cinema. Those views were many, but mostly they can be subdivided into filmgoing, film and theatre, money, education and censorship. So let us address each one of these in turn.

Filmgoing

Shaw was a keen cinemagoer from the 1900s onwards and throughout his long life. He enjoyed the full range of dramatic delights on offer, even if he thought some of the performers poor. In this extract from a 1912 letter to the renowned stage actress Mrs Patrick Campbell, he praises Max Linder and an unnamed Danish actress (maybe Asta Nielsen):

Do you ever study the cinema? I, who go to an ordinary theatre with effort and reluctance, cannot keep away from the cinema. The actor I know best is Max Linder, though I never heard his voice or saw his actual body in my life. But the difficulty is that though good looks and grace are supremely important in the cinema, most of the films are still made from pictures of second, third and fourth rate actresses, whose delighted willingness and energy, far from making up for their commonness, make it harder to bear. There is one woman whom I should shoot if her photograph were vulnerable. At Strassburg, however, I saw a drama which had evidently been played by a first rate Danish (or otherwise Scandanavian) company,with a really attractive leading lady, very sympathetic and expressive, without classical features but with sympathetic good looks …

Interesting that Shaw at this stage cannot really see the cinema as anything other than photographed drama rather than something truly with a life of its own, to be judged by what one saw on the screen rather than by what one thought of the process by which it got there.

Shaw’s most notable commitment to cinemagoing was as one of the original subscribers to the Film Society, formed in 1925 by a coterie of British intellectuals as a place to show artistic films (chiefly from the Soviet Union) which were unviewable elsewhere. Ivor Montagu was the founder: other notable members included Julian Huxley, John Maynard Keynes, Roger Fry, Michael Balcon, John Gielgud and Ellen Terry. It formed the cornerstone of British intellectual film culture.

Film and theatre

Shaw was fascinated by the relationship between film and stage, as a professional writer and as a theorist. He saw that films were a threat to the drama (and would be all the more so once they acquired sound), not least for what they exposed of the specialised nature of theatre. In Shaw’s eyes, the cinema was open to a wide range of talents, while “the art of the theatre is a far more specialized, more limited, and consequently more exacting art than the art of the picture palace”. This simplistic view, from 1915, he may have revised in later years, but he saw clearly (at a time when many still believed that better films would be made by employing renowned playwrights) that the two arts differed significantly. In 1921 he wrote:

I agree with [Eugène] Brieux that cinematography is an art in itself, and that the practice of transfering stage plays from the stage to the screen is a superstition. It imposes the very narrow physical limits of the stage on the practically boundless screen; and it deprives the stage play of the only feature that distinguishes Lear from Maria Marten or The Murder in the Red Barn; that is, the dialogue. Its success is in direct propotion to the quantity of screen stuff interpolated by the film producer; the more complete the transformation, the better the result.

Authors should write for the stage and the screen; but they should not try to kill the two birds with one stone.

Money

Shaw was a professional writer. He wrote plays to air social issues, but also to make money. So he was interested in the cinema as it affected him as a writer, and also (from his socialist viewpoint) as a capitalistic enterprise. Shaw received many invitations from film companies to film his plays, requests which he turned down throughout the silent era, even as the proffered sums grew higher and higher, for two reasons: (i) because his works could only best be served by the talkies, and (ii) because once a play had be filmed, it would lose its commercial worth in the theatres. This interesting latter point he made clear in a letter to writer William Lestoq in 1919:

Pygmalion is not available for filming.

Never let anyone tempt you to have a play of yours filmed until it is stone dead. The picture palace kills it for the theatre with mortal certainty. Pygmalion is still alive and kicking very heartily.

But it was also the deals that he was being offered that offended him. He knew, in any case, that all the movie magnates really wanted from him was his name – the product they could turn to their own desires as they pleased, if he would let them. Shaw’s canny business head is revealed in this letter from 1921:

Hearst [William Randolph Hearst, the press baron, was a movie producer as well] has sounded me out on the subject of films; but he has never suggested that his very handsome purchases of serial rights from me should carry Movie Rights with them. On the contrary, it is I who have been sounding him on the subject, because if I sell a film down for £10,000 down, the taxation is so enormous, both on the sum itself and on all the rest of my income (which is raised in the scale by the addition of this big sum), that I prefer an annual payment spread over years; and yet as the film firms are here today and gone tomorrow, one cannot trust to anything but a lump sum in dealing with them. A permanent institution like W.R.H. [William Randolph Hearst] would be much safer.

Shaw signed no contract with Hearst or anyone else. Wary of the silly sums of money being waved at him, warier still of how his art might be spoiled by the screen, he hung on until sound films (whose potential had interested him since the earliest synchronised sound experiments from the 1900s) were a commercial reality. However, he has less control over what got produced in some European countries, and a Czechoslovakian version of Cashel Byron’s Profession, Román boxera, appeared in 1921, while a little-known Austrian film, Jedermanns Weib, made in 1924 by Alexander Korda and starring his wife Maria, is loosely based on Pygmalion (she plays a Montmartre flower seller who is turned into a high society lady). The film was released in Britain in 1926 (as The Folly of Doubt) but there seems no evidence that Shaw was aware of it. (Korda in later years bid for the rights for Shaw’s works, but it was another Hungarian, Gabriel Pascal, who finally gained Shaw’s trust).

Education

Shaw demonstrated his habitual imagination in his views on the value of the cinematograph in education. Most social commentators, if they could find any good word for the early cinema, would point to its possible educative possibilities, but Shaw knew how narrow such sentiments usually were. It was the cinema itself that was an education, as he wrote in The Bioscope in 1914:

The cinematograph begins educating people when the projection lantern begins clicking, and does not stop until it leaves off. Whether it is shewing [sic] you what the South Polar ice barrier is like through the films of Mr [Herbert] Ponting, or making you silly and sentimental by pictorial novelets, it is educating you all the time. And it is educating you far more effectively when you think it is only amusing you than when it is avowedly instructing you in the habits of lobsters.

The cinema was not there to teach the moral virtues but rather the “immoral virtues” of “elegance, grace, beauty … which are so much more important than the moral ones”. Shaw is being too clever, as usual, but when he ends this intellectual sally by by declaring that the cinematograph “could easily make our ugliness look ridiculous” then one starts to understand what he is trying to say. The cinema teaches us to appreciate the beautiful. How true.

Censorship

On censorship, Shaw was bracingly sensible. In this 1928 piece, he defends screenings of Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin and the British film Dawn (about the execution of Nurse Edith Cavell in the First World War):

All the censorships, including film censorships, are merely pretexts for retaining a legal or quasi-legal power to suppress works which the authorities dislike. No film or play is ever interfered with merely because it is vicious. Dozens of films which carry the art of stimulating crude passion of every kind to the utmost possible point – aphrodisiac films, films of hatred, violence, murder, and jingoism – appear every season and pass unchallenged under the censor’s certificates. Then suddenly a film is suppressed, and a fuss got up about its morals, or its effect on our foreign relations … One of the best films ever produced as a work of pictorial art has for its subject a naval mutiny in the Russian Fleet in 1904 … The War Office and the Admiralty immediately object to it because it does not represent the quarterdeck and G.H.Q as peopled exclusively by popular and gallant angels in uniform. It is suppressed. Then comes the Edith Cavell film. It is an extraordinarily impressive demonstration of the peculiar horror of war as placing the rules of fighting above the doctrine of Christ, and geographical patriotism about humanity. No matter: the film is at once suppressed on the ridiculous pretext that it might offend Germany … The screen may wallow in ever extremity of vulgarity and villainy provided it whitewashes authority. But let it shew a single fleck on the whitewash, and no excellence, moral, pictorial, or histrionic, can save it from prompt suppression and defamation. That is what censorship means.

Shaw’s views on cinema are boldly expressed, and touch upon every corner of its production and its relationship to society. It is fortunate that there is a volume (to which this post is much indebted) which gathers together his writings on film: Bernard F. Dukore, Bernard Shaw on Cinema (1997), which I warmly recommend. Shaw did not wholly understand the medium about which he was so ready with an opinion (something which could be said about Shaw and any number of subjects). His careful nurturing of his plays until the talkies arrived was no protection against the persuasive tongues of such producers who promised him faithfulness to his text, and the first two Shaw talkies, How He Lied to Her Husband (1931) and Arms and the Man (1932) talked too much. Only with Pygmalion (1938), one of the jewels of 1930s British cinema, did Shaw and the cinema finally understand one another (and only then after two unofficial versions, one German (1935), one Dutch (1937), had vulgarised his work to the point of unrecognisability).

‘Well this is a surprise, have you all come to see me?’ Shaw addresses the Movietone newsreel cameras in 1929, from http://www.movietone.com

Is there anything else to add to Shaw’s interest in film in the silent era? Well, there was Shaw the film performer. As told in an earlier Pen and Pictures post, Shaw appeared in J.M. Barrie’s spoof cowboy film How Men Love, in 1914. In 1917 he turned up in the prologue, filmed at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts, to the film Masks and Faces. He gives a silent ‘interview’ to Pathe Gazette in a 1927 newsreel available on the British Pathe site.

But for Shaw the word was everything, and it is no surprise that his real film debut came with sound. He made a short film of some kind in 1926 (according to Dukore it was a ‘filmed interview’ made using film and phonograph, produced in Italy), and may have been interviewed for the Lee De Forest Phonofilm system in 1927 (information on this is contradictory). But it was in 1928 that he caused a sensation with his ebullient address to the Movietone newsreel cameras:

Well this is a surprise, have you all come to see me … ladies and gentlemen well I should never have expected this … its extremely kind of you and I’m very glad to see you … I’m very glad to have come as I like people to see me, I don’t know how it is but people who only know me from reading my books or sometimes see my plays get an unpleasant impression of me, and the people who meet me as you’ve been kind enough to meet me, when they see that I’m a most harmless person, I’m really a most kindly person …

This was a man who needed the camera to hear him.

(You can see and hear the 1928 interview at www.movietone.com – you have to register first, but it is free thereafter. The site dates the film as 1929, but that is for its British release).