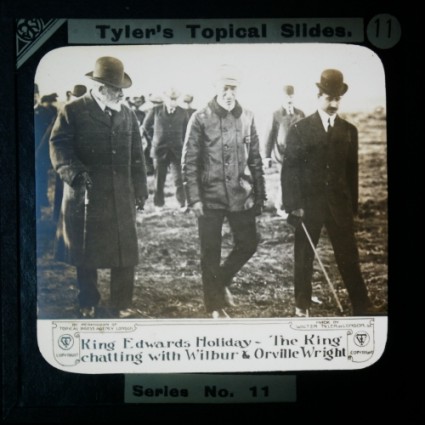

King Edward VII meeting the aviators Orville and Wilbur Wright at Pau in France, Tyler’s Topical Slides series 11 (March 1909), from the LUCERNA database

A while ago we told you about the LUCERNA database, a directory of information on the magic lantern and home to digitised copies of lantern slides held in public and private collections. The site – a joint project by Universität Trier, Screen Archive South East, the Magic Lantern Society, UK; and Indiana University, but chiefly a labour of love by media historian Richard Crangle – demonstrates the range and depth of the magic lantern, not only in terms of subjects covered (fictional and non-fictional) but in the period of time it covers. The magic lantern continued well into the twentieth century (one of the leading British film trade papers was known as the Kinematograph and Lantern Weekly up to 1919) and arguably has never gone away, going through such incarnations as the slide carousel for family photos of a couple of generations ago through to the PowerPoint presentations of today.

New slides continue to be added to the site, and recently a set was added which is of huge interest to this enthusiast for historical news media, because it provides evidence of something I had felt certain had to have existed somewhere but had never seen, a sort of missing link between news photography and newsreels – the topical lantern slide.

Tyler’s Topical Slides, series 5, showing the visit of Basuto Chiefs to London in February 1909, where they were challenging the decision of the British government to include their land Lesotho within the Union of South Africa

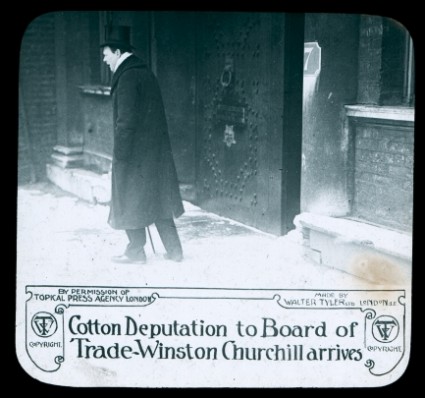

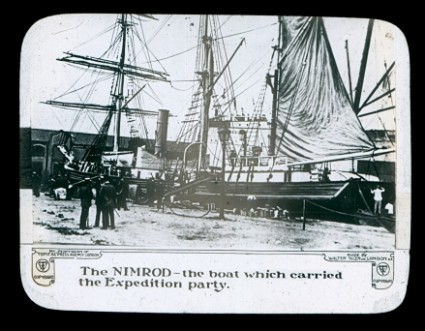

The collection is Tyler’s Topical Slides, a set of lantern slides reporting on current events put out by Walter Tyler, a renowed lantern manufacturer whose business subsequently (after his death in 1909) diversified into motion picture equipment and film distribution as the Tyler Film Company. There are some 370 slides, arranged in 40 sets that date 1909-10. Each set is numbered, the highest number being series no. 87, from which it can be extraopolated that the slides were issued weekly. The number of slides ranges from 1 to 20 per set, but that is a reflection of what survives. Each slides has a photograph, supplied by the Topical Press Agency, a well-known photograph agency of the period (no connection with the Topical Film Company, which produced the Topical Budget newsreel). Each has a one-line caption describing the story. They would have been shown in sequence, long enough for an audience to take in the news item before the next slide would follow. They are exactly like newsreels – before there were newsreels.

The first newsreel in Britain, Pathé’s Animated Gazette, was first issued in June 1910. Newsreels had existed earlier in France, and of course films of news events were as old as film itself, but a newsreel as a collection of topical news stories gathered on a single reel was something new. What has been understood until now is that the inspiration for newsreels was photo-illustrated newspapers (such as The Daily Mirror and The Daily Sketch) which were interested in the visual impact of stories (other newspapers, such as The Times, did not carry photographs until some years later). What was not known, at least by me, was that there was another, direct precursor, the news or topical slide.

Tyler’s Topical Slides appear to have been issued from January 1909 – so a year and a half before the first newsreel was shown in Britain. They ran until at least September 1910, when the growing popularity of newsreels probably rendered them unviable commercially. We don’t know for certain, but it seems highly like that the slides were shown in cinemas, as well as variety theatres and town halls putting on mixed public entertainments (including films). In subject matter, style and adress, the topical slides are effectively identical to the first newsreels, which would open with a title and simple description of the action, followed by 30 seconds or so of film (withour further intertitles cut into the film), followed then by the next news story.

Tyler’s Topical Slides, series 11, showing Lieutenant Shackleton’s ship The Nimrod (Shackleton’s party arrived in New Zealand following their failed attempt to reach the South Pole on 23 March 1909 – this is therefore a photograph of the Nimrod before it sailed south)

The subject matter is the same as well – the popular news stories of the day, with an emphasis on personalities, especially royalty, sport, tradition and diverting incidents of the day, light-heartedly expressed with little overt political comment. In audience impact the slides would have worked in the same way as newsreels, because newsreels depended on the audience’s prior knowledge of the news story. They would have read about these topical subjects in their daily newspapers – now the weekly topical slides, or the weekly newsreel (newsreels started out weekly in the UK before becoming bi-weekly), showed them the pictures to supplement what they already knew, what had become common knowledge. The pictures completed the picture.

Winston Churchill (when President of the Board of Trade) as featured in Tyler’s Topical Slides, series 9 (February 1909)

How widely were such news or topical slides shown? Did any other company produce them apart from Tyler? It would be important to know, because either we are looking at a one-off freakish anticipation of the newsreel, or it is evidence of a significant news medium not hitherto written about in news media histories (to the best of my knowledge). The importance could lie not just in the ‘missing link’, but because it would be supporting evidence for the thesis that with the rise of the different news media at the turn of the 19th/20th centuries came a vital element of what makes up the news – consumer choice. The news does not exist in any one medium. It lies in the mind of each and everyone one of us who goes out looking for news, and finds it relayed through a variety of media, from which we pick and choose what we understand the news to be. It’s a part of what it is to be modern. Tyler’s Topical Slides show that the choice on offer in 1909-10 was that much greater than previously thought.

Tyler’s Topical Slides can be found on the LUCERNA database, simply by typing in “tyler” into the search box, then by ticking the box marked “show” next to the text that reads “88 sets with title containing ‘tyler’”. Being in series order they are in chronological order, and it would not take too much research to identify dates for many of the events depicted, and from that to extrapolate on what day of the week the series was released (assuming it was always the same day of the week) and what gap there was being an event occuring and Tyler being able to include this on the slides that it distributed.

How did such a business work when news subjects go so rapidly out of date? How extensive would the distribution have to have been to make it economical? How did distribution work, and how widespread was it? So many questions worth researching.

If anyone knows of any other examples of topical lantern slides which were released in series form, please do get in touch. There’s more to be found out – there has to be.