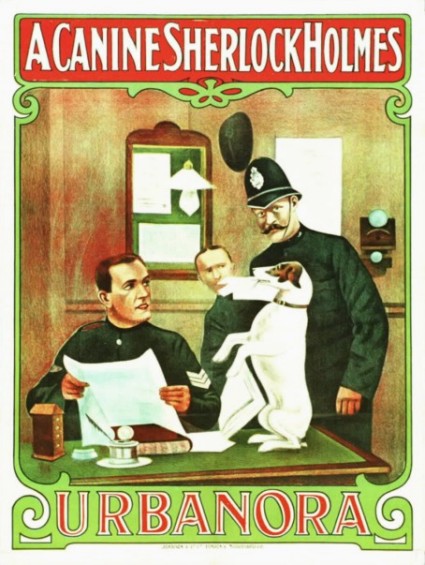

Spot the Urbanora Dog (not a competition, by the way – ah, the old jokes are the best)

Well, how could I possibly resist publishing this iconic image? Anyone who knows your scribe’s nom de plume or particular interest in the exploits of dogs in silent films will no doubt be cheering, and very probably rushing off to book hotels and transportation at the very thought of the legendary Charles Urban-produced film A Canine Sherlock Holmes (1912) turning up at the British Silent Film Festival, which takes place in Cambridge, 19-22 April 2012.

The festival is in its fifteenth year, and being in celebratory mood it has put together a sort of greatest hits programme, which looks remarkably ambitious for a four day event. It is certainly packed with treasures and diverting oddities. The festival started out fifteen years ago as a quaint mix of academic papers and obscure British silents, appealing to a select if dedicated bunch of people. It hit hard times a few years ago, but a shift in programming to feature films with some special events, combining imaginatively selected British silents with world classics looks to have paid dividends. Among the better-known titles in the programme below, there are Turksib, Visage d’Enfants and The Great White Silence, while the Dodge Brothers accompanying Abram Room’s The Ghost that Never Returns is bound to be popular. But let me recommend also The Blackguard, directed by Graham ‘The White Shadow’ Cutts; the programme of Fred Paul’s proto-horror short films (especially The Jest); the modestly pleasing W.W. Jacobs films (including The Head of the Family, filmed in fair Whitstable, the town where I grew up); another Fred Paul film, Lady Windermere’s Fan (not exactly Lubitsch, but well worth watching) and the What the Silent Censor Saw programme, which should show some of those extant films we recently highlighted as having been rejected by the BBFC for screening in the UK. There are tributes to Charles Dickens and P.G. Wodehouse, and more dog-centred entertainment with the tear-jerking feature film Owd Bob (surely the loyal old sheepdog can’t be a killer…?) and a programme of shorts that includes the heartening Dog Outwits the Kidnappers, with Cecil Hepworth’s Rover driving a car with aplomb.

Here’s the full programme.

19.04.2012

09.00 – 17.00 Registration (Arts Picture House)

10.30 The Bachelor’s Baby (Arts Picturehouse – Screen 3)

Romantic comedy about a bachelor who discovers an abandoned baby whilst on a motorcycle tour of the Lake District. Uncertain of what to do with the foundling, he hands it to a retired captain living next door to his unrequited childhood sweetheart and her young niece. Meanwhile, assuming it stolen, the child’s mother and an array of interfering busy-bodies set out to look for the child in a series of comic interludes, mistaken identities and baby swaps. Does the mother want the baby back and what of the attractive niece who catches the eye of the eponymous bachelor?Dir: Arthur Rooke. With: Malcolm Tod, Tom Reynolds, Peggy Woodward, Constance Worth, Haidie Wright. GB 1922, 67mins.

Plus

Ordeal by Golf

The first of our P.G. Wodehouse golfing tales about two golfers and their ‘eternal caddy’, a man who supplements his income by stealing ‘lost’ balls and selling them back to their original owners. Inevitably, golf is much more than just a game here and when an elderly boss seeks to appoint a new company treasurer, he challenges the two potential candidates to a golfing match as ‘the only way to judge a man’s true character’. But is beating the boss really such a good idea?Dir: Andrew P Wilson. With: Harry Beasley. GB 1924, 26mins

13.15 The Only Way (Arts Picturehouse – Screen 2)

The final major Dickens adaptation of the silent era, The Only Way is a lavish adaptation of the popular stage play of the same name, itself a rather free adaptation of A Tale of Two Cities. Produced and directed by the ambitious Herbert Wilcox, it stars legendary theatre actor-manager Sir John Martin Harvey as Sydney Carton, the English advocate who is given the chance to redeem his wasted life by saving the life of his near double, a French aristocrat in exile from revolutionary France threatened with the guillotine.Dir: Herbert Wilcox. With: John Martin-Harvey, Ben Webster, Madge Stuart, Jean Jay. GB 1926, 107mins

13.30 Young Woodley (Arts Picturehouse – Screen 3)

One of the most impressive and sensitively directed British films of the late silent era, Young Woodley is based on John Van Druten’s controversial stage play of 1925 which had already fallen foul of the Lord Chamberlain. Its the story of a dreamy young college boy who falls for the Headmaster’s wife, the beautiful Laura Simmons (Madeleine Carroll), herself trapped in a stale marriage. Originally shot in 1928 as a full-blooded silent, (the version screened here), the film remained unreleased until 1930 when it was refashioned into an early sound feature. Somewhat reminiscent of both Tea and Sympathy and The Browning Version, this little seen gem is more than deserving of a much belated reappraisal.Dir: Thomas Bentley. With: Frank Lawton, Madeleine Carroll, Sam Livesey, Aubrey Mather

GB 1928, 1hr 33mins

Plus Young Woodley Sound Trailer. 1930. 3.5mins

15.30 Grand Guignol – The Last Appeal + The Jest + A Game for Two (Arts Picturehouse – Screen 2)

Fred Paul’s Grand Guignol short films, A Game for Two, The Jest, The Gentle Doctor and The Last Appeal stand out for their remarkable plots, all with a cruel twist in the tale, and their fatalistic atmosphere. Fred Paul himself declared ‘I attempt to show life as it really is, its sordidness and cruelty; the diabolical humour of the destiny we call fate, which plays with us as it will, raises us to high places or drags us to the gutter; allows one man to rob the widows and orphans of their all and makes a criminal of the starving wretch who in his misery has stolen a mouthful of bread. The four surviving short films are here presented with a script by Michael Eaton.Dir Fred Paul: GB 1921. Running time approx 70mins

17.30 The Boatswain’s Mate + A Will and a Way (Arts Picturehouse – Screen 3)

At the Beehive Inn, the widowed landlady Mrs Waters has no shortage of gentlemen admirers willing to ‘marry a pub’. But she wants to marry an ‘ero and pub regular George sets out to prove himself by rescuing her from a fake burglary which he stages with an itinerant Victor Maclagen, who turns up looking for work. But the plan goes awry when the feisty landlady proves that she’s more than a match for either of them.Dir: Manning Haynes. With: Florence Turner, Victor Maclagen, Johnny Butt. GB 1924,26 mins.

Plus

A Will and a Way

In the peaceful village of Claybury a wedding takes place and two locals set the scene for this delightful romantic comedy when they announce ‘This be a rare place for a wedding. Not as the gals be better lookin’ than others – they be sharper’. Meanwhile the recently deceased, Sportin’ Green, leaves his fortune to his nephew Foxy on the proviso that he marries the first woman to ask him. Cue an array of fortune-seeking widows, elderly spinsters and men in drag, all vying to pop the question first and a series of hilarious interludes with echoes of Buster Keaton’s Seven Chances.Dir: Manning Haynes. With Ernest Hendry, Johnny Butt, Cynthia Murtagh, Charles Ashton. GB 1922, 45mins

19.00 Gala Screening – Visages D’Enfants (Faces of Children) (Arts Picturehouse – Screen 1)

An astounding portrait of tragedy from one of the founding masters of French poetic realism and filmed through the eyes of a young boy haunted by the death of his mother. Set in a Swiss alpine community the film opens with her funeral and deals with the aftermath as the boy, brilliantly played by child actor Jean Forest, tries to come to terms with this life-changing event, his own grief and the prospect of a new stepmother and sister. Compared to Truffaut’s 400 Blows in its sympathy for the child’s eye view, historian Jean Mitry could give no higher accolade when he said, ‘If I could select only one film from the entire French production of the 1920s, surely it is Faces of Children that I would save’ .Dir: Jacques Feyder.With: Jean Forest, Victor Vina, Arlette Pevran, Henri Duval. France 1925, 114mins

20.04.2012

09.00 New Discoveries: (The Ones that got away) Tony Fletcher (Arts Picturehouse – Screen 3)

A tantalising programme of rare Edwardian short films selected and presented by long-term Festival collaborator Tony Fletcher, and displaying the rich diversity held in the BFI National Archive. This selection includes comedies such as The Cheekiest Man on Earth (1908) and A New Hat for Nothing (1910), Arthur Melbourne Cooper’s mechanical animation Road Hogs in Toyland (1911), moral tales like A Great Temptation (1906), visual spectacles such as Wonders of the Geomatograph (1910) and Pageant of New Romney (1910) an early colour experiment by pioneer G.A. Smith, to the Edison Company’s adaptation of the Tennyson poem Lady Clare (1912) filmed at Arundel Castle.Presented by Tony Fletcher

Dir: Various. Running time 85mins

11.00 – 12.30 The Woman’s Portion – IWM event (Arts Picturehouse – Screen 3)

A fascinating programme of films about women’s contribution during the Great War, including recruitment films for the Land Army and Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps, propaganda films encouraging the use of National Kitchens and extolling the virtues of frugality. The programme includes the recently restored version of c1918 fictionalised propaganda film The Woman’s Portion about the need for women to accept separation from, and loss of, their husbands fighting on the Front. The IWM has recently re-edited, tinted and provided a new piano score by the composer, Ian Lynn.Programme will be presented by Matt Lee and Toby Haggith

Dir: Various. GB 1917-1918. Running time approx 80mins

11.00 Tansy (Emmanuel College)

Alma Taylor stars as Tansy, a shepherd girl caught up in a love triangle between two brothers which results in her eviction from her beloved farm. Played out against the backdrop of the beautiful Sussex Downs, and based on a popular novel of the time by Tickner Edwardes, the film displays all the pictorial beauty and naturalism for which Hepworth was renowned. Tansy was a lucky survivor among Hepworth’s feature films when the majority of his work was seized and tragically melted down following his bankruptcy.Dir: Cecil M. Hepworth. With: Alma Taylor, James Carew, Gerald Ames, Hugh Clifton. GB 1921, 63 mins

13.30 The Long Hole + The Clicking of Cuthbert (Arts Picturehouse – Screen 3)

Two classics from P.G. Wodehouse’s golfing tales here presented with readings from the original stories. Originally presented in 6 parts The Clicking of Cuthbert was the first. Set in the suburban paradise of Wood Hills where two rival camps, The Golfers and The Cultured, vie for supremacy. When Cuthbert is forced to retrieve a ball, accidentally smashed a ball through the window into a literary society meeting, he falls for the charms of the cultured poetess Adeline. But she wants an intellectual, so Cuthbert attends readings of Soviet ‘misery lit’ by a famous visiting Bolshevik in the hope of becoming one. But when the Bolshevik announces his own love of golf, the Cultured Adeline is forced to rethink her own prejudices against the game.Plus

The Long Hole

Two rival golfers compete for the attention of an attractive young woman, each convinced that they would stand a chance if the other were out of the way. So they decide to settle the matter with a round of golf comprising a single hole, teeing off from first green and ending in the doorway of the Majestic Hotel the following day. But en route, the pair are forced to play fast and loose with the rules as they deal with the mud of an English summer and balls accidentally chipped into motorcars and boats. What a pity that neither of them had considered whether the object of their mutual desire was interested in them.Dir: Andrew P. Wilson. With Roger Keyes, Harry Beasley, Charles Courtneidge, Daphne Williams. GB 1924, 25mins/32mins

13.30 The Lure of Crooning Water (Emmanuel College)

Romance and melodrama mingle in this tale of a city seductress who lures a farmer away from his wife and family. Ivy Duke plays a famous actress ordered by her doctor-lover to take a rest cure at the idyllic Crooning Water Farm. But she’s unable to resist flirting with the unworldly farmer (Guy Newall) under the nose of his hard-working wife who can do little to distract him from her spoilt love-rival. The British countryside has never looked more glorious and there are some comedy moments –including the ‘smoking baby’ sequence. The film was a critical success on its release with Kinematograph Weekly proclaiming it as ‘a triumph for the British producer. It disposes once and for all the ridiculous argument that good films cannot be made in this country’.Dir: Arthur Rooke. Starring: Guy Newall, Ivy Duke, Douglas Munro, Mary Dibley. GB 1920 104mins

15.30 The Head of the Family (Arts Picturehouse – Screen 3)

Set in a Kentish seafaring community, Mrs Green is horribly bullied by her second husband who threatens to sell off the family home that belonged to her son, who was lost at sea and presumed dead. But when the despairing woman meets a friendly sailor looking for lodgings, the two hatch a plan to thwart her husband’s schemes by pretending that the young man is her long-lost son, back to claim his place at The Head of the Family. The locations are a delight and the cinematography praised by contemporary critics who claimed that W.W. Jacobs, with his international reputation, would be enough to draw the crowds – a poignant reminder of how popular tastes in literature have changed.Dir: Manning Haynes. Starring Johnny Butt, Daisy England, Charles Ashton, Moore Marriott. GB 1922 73 mins

With

Rough Seas Around British Coasts

A mesmerizing actuality film displaying the power of high tides and rough seas.GB, 1929, 9 mins

15.30 Lady Windermere’s Fan (Emmanuel College)

The first film adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s classic satire on Victorian marriage and society. Lady Windermere, convinced that her husband is being unfaithful with a certain Mrs Erlynne, is further distressed to discover that the ‘other woman’ has been invited to her birthday ball. So she embarks on her own affair to get even. But all is not what it seems and, Mrs Erlynne sacrifices her own reputation to save Lord and Lady Windermere’s marriage with the final plot revelation, explaining her motives.Dir: Fred Paul. With: Milton Rosmer, Irene Rooke, Nigel Playfair, Netta Westcott. GB 1916, 72 mins

17.30 What the Silent Censor Saw! (Arts Picturehouse – Screen 2)

To celebrate 100 years of film classification by the BBFC we look at the history of this remarkable institution and its decision making processes. Featuring clips from films illustrating various censorship issues – sex, drugs and bullfighting as well as the wonderful Adrian Brunel spoof, Cut it Out: a Day in the Life of a film Censor.Introduced by Lucy Betts of the BBFC and Bryony Dixon of the BFI

Dir: various. Running time approx. 90mins.

17.30 The Man Without Desire (Emmanuel College)

Adrian Brunel’s first feature film is a fascinating curio, filmed on location in Venice, bearing hallmarks of German Expressionism and shifting between the 18th and 20th Centuries. Novello’s other-worldly beauty and sexual ambiguity is perfect for the role of Count Vittorio Dandolo, an 18th Century Venetian nobleman, put into a state of suspended animation following the murder of his lover, who is revived into the present with unexpected consequences.Dir: Adrian Brunel. With Ivor Novello, Nina Vanno, Sergio Mari, Christopher Walker. GB 1923, 107mins

19.15 The First Born – Gala Screening (Arts Picturehouse – Screen 1)

With new musical score from Stephen HorneA tour de force of late silent filmmaking and a heady mix of politics, infidelity, sex and passion, The First Born was adapted by Miles Mander from his own novel and play with a script by Alma Reville, Alfred Hitchcock’s talented wife. It concerns the relationship between Sir Hugh Boycott (Mander) and his young bride Madeleine, sensitively played by a pre-blonde Madeleine Carroll. Their passionate relationship founders when she fails to produce an heir. The print has recently been fully restored by the BFI National Archive with its original delicate tinting.

Dir: Miles Mander. With: Miles Mander, Madeleine Carroll, John Loder. GB 1928, 88mins.

21.04.2012

09.00 Livingstone (Arts Picturehouse – Screen 3)

A rare screening of this fascinating biopic starring actor, director and explorer M.A. Wetherell in the title role. The film traces Livingstone’s physical and spiritual journey from his humble Scottish home to Africa and his fight against slavery. Wetherell travelled over 25,000 miles to produce the film, which is largely shot on location in the places visited by Livingstone with the indigenous African Tribes people playing themselves. The film was highly praised on its release for combining drama, sensitive performances with stunning scenery and travelogue. The Cinema News and Property Gazette stated, ‘The picture was warmly received at its Albert Hall presentation last week, and the audience seemed particularly pleased with the magnificent views of the Victoria Falls. As for the crocodiles, no disciple of Ufa could have made them more terrible or more worthy to be respected’ It is here presented in the only known extant 16mm print courtesy of the Archive Film Agency.Dir: M.A. Wetherell. With M.A. Wetherell, Molly Rogers, Douglas Cator, Robson Paige. GB 1926, 62mins

Presented in association with the Archive Film Agency

09.00 Mist in the Valley (Emmanuel College)

Produced and directed by Cecil Hepworth, based on the original novel by Dorin Craig, this is a story of a lonely heiress, played by Alma Taylor, who runs away from an unhappy home. She meets her future husband whilst destitute and they soon marry. However, their happiness is short-lived as her father is murdered and our heroine becomes the prime suspect! A Courtroom drama ensues with an unexpected twist at the end.Dir: Cecil M. Hepworth. With Alma Taylor, G.H. Mulcaster, James Carew, Esme Hubbard. UK, 1923 75mins

11.00 Fun Before the Footlights: The Origins of Undergraduate Humour (Arts Picturehouse – Screen 2)

The British tradition of absurdist humour didn’t start with The Goons, Pete and Dud, or Monty Python – not by a long chalk. The slightly silly antics of the so-called intelligentsia are to be found in a series of short films of the 1920s which delight in anti establishment cheek and a desire to take the **** out of cinema itself (outrageous!) with a pastiche travelogue, a bogus newsreel (the Typical Budget) and a send up of the Censor himself. With an introduction by Jo Botting (BFI)Dir: various. Running time 90mins

11.00 Family Matinee – Silent film fun with Animal Stars (Arts Picture House)

The Artist’s ‘Uggie’ proved how important it is to have a clever dog in your silent movie and we’ve got a kennel full – driving cars, doing tricks and getting their owners out of scrapes along with assorted parrots, monkeys, horses, insects and goodness knows what else – fun silent comedies for the whole family with films from crime-fighting dogs in 1906 to Charley Chase trying to bath a Great Dane in 1927, all introduced, explained and accompanied by Neil Brand.Dir: various. Running time approx 80mins

13.30 Fante Anna (Gypsy Anna) (Emmanuel College)

Presented in association with The Norwegian Film Institute and Lillehammer UniversityOne of the great films of the Norwegian silent canon, starring Asta Nielsen, one of the greatest actresses of the period. Anna, a gipsy child is discovered in the arms of her dead mother by a farmhand and adopted by the Storleins, his employers. But Anna (Nielson) grows into a wild child, constantly getting her step brother into trouble, until mother Storlein can take no more and Anna is forced to leave. As the years pass, Anna falls in love with her step brother, but Jon, the farmhand has also fallen for Anna. Their fate is bound together and one of the rivals will be forced to save her life. This newly restored film is here presented by composer Halldor Krogh whose new symphonic music score will be played with the film.

Dir: Rasmus Breistein. With Asta Nielsen, Einar Tveito, Johanne Bruhn Norway 1920

15.30 The Bohemian Girl (Arts Picturehouse – Screen 3)

Based on William Balfe’s operetta of the same name, Knoles’ lavish production stars Ivor Novello as Thaddeus, an exiled Polish officer who joins a gypsy community in Bohemia to escape the Austrian military. Here he meets and falls in love with Arline, a young woman of noble birth stolen as a baby and brought up as a gypsy. But the Queen of the Gypsies has also fallen in love with Thaddeus and, jealous of the younger woman, she has Arline arrested for theft. Notable for its cast of theatrical luminaries, and with a tantalizing and rare glimpse of Helen Terry, the film was praised for its staging, but criticized for its overall lack of drama.Dir: Harley Knoles. Starring Ivor Novello, Ellen Terry, Gladys Cooper, Constance Collier. GB 1922, 70mins.

15.30 The Great White Silence (Emmanuel College)

In 1910, Captain Robert Falcon Scott led what he hoped would be the first successful team to reach the South Pole. But the expedition also had a complex (and completely genuine) scientific brief. Scott’s decision to include a cameraman in his expedition team was a remarkable one for its time, and it is thanks to his vision – and to Herbert Ponting’s superb eye – that, a century later, we have an astonishing visual account of his tragic quest. The film built on Ponting’s lecture, introducing intertitles, as well as his own stills, maps, portraits and paintings, to create a narrative of the tragic events. The film was lavishly restored by the BFI National Archive in 2010 for the centenary of the expedition with original tints and tones and a newly commissioned score by Simon Fisher-Turner.Dir: Herbert G. Ponting. With: Capt. Robert Falcon Scott. GB 1924, 108mins.

17.30 A Couple of Down and Outs (Arts Picturehouse – Screen 3)

In this timely reprise for the War Horse of its day, a man recognizes the horse that he cared for on the battlefields of the First World War as it is being led off to the knackers yard. Man and horse go on the run in a beautifully told tale of official brutality and individual compassion. Print courtesy of the EYE Film Institute Amsterdam.Dir. Walter Summers. With: Rex Davis, Edna Best. GB 1923, 64mins

19.00 Turksib – Gala Screening (Emmanuel College)

With live music from Bronnt Industries KapitalThis masterpiece of Soviet film making describes the construction of the great Turkestan-Siberia railway as it progresses 1445km through the vast Steppes and deserts of Kazakhstan. The railway was one of the great achievements of the Soviet Five Year Plan and Turin’s film captures the revolutionary fervour of the endeavour with it’s symphonic form and rhythms, backed up by Bronnt Industries fabulous new score. ‘A lyrical, humane, superbly edited masterpiece’ The Guardian.

Dir: Viktor Turin, USSR 1929, 78mins

21.00 Here’s a Health to the Barley Mow – Gala Screening (Emmanuel College)

A cornucopia of short films from the acclaimed BFI DVD release, Here’s a Health to the Barley Mow, featuring a century of folk customs and ancient rural games from mummers and morris dancers, to extreme sports and village customs. The programme will include some of the earliest known film footage of English folk traditions from around the country, some collected by pioneer folk revivalist Cecil Sharp in 1911. Live musical accompaniment will be provided by renowned musicians, concertina player Rob Harbron with Miranda Rutter on fiddle in what promises to be a unique and unmissable event.Dir: various. GB. Total running time approx 80mins.

22.04.2012

09.00 The Blackguard (Arts Picturehouse – Screen 3)

Based on Raymond Paton’s 1923 novel about a penniless and wounded violinist who saves a young Russian princess from execution during the 1917 Russian Revolution. The film was shot at UFA’s Babelsberger Studios in Germany as a co-production with Gainsborough, and is noteworthy for Hitchcock’s contribution as Art Director. The Blackguard is a good example of big 1920s European film making with impressive crowd scenes, and it never looks less than fabulous.Dir: Graham Cutts. With Jane Novak, Walter Rilla, Frank Stanmore. GB/Germany 1925. 80mins

09.15 Owd Bob (Emmanuel College)

Taken from the novel by Alfred Ollivant, Edwards’ charming film is a tale of love and rivalry in the Cumbrian hills. With his loyal dog Bob close by his side, young farmer James Moore is new to the valley, much to the annoyance of long-standing land owner Adam McAdam. However, real trouble comes to this close-knit community with the discovery of the bodies of savagely killed sheep. Acrimony and accusations ensue causing a deep set family feud. Who is to blame? Could Bob really be the culprit? Featuring some evocative location photography of the Lake District.Dir: Henry Edwards. With: Ralph Forbes, James Carew, J. Fisher. GB 1924 68mins

11.00 Ask the Experts – Silent film in the 21st century (Emmanuel College)

The worldwide success of The Artist has focused attention on silent cinema like never before. Will this phenomenon translate into greater interest in silent film? Or is it in fact the result of increased interest in silent cinema rather than a cause? In this panel session specialists from the ‘British Silent Film Festival’, explain their passion for silent film, look at other examples of silent film in the 21st century and trace the development of silent film in the 20th century to explain its enduring appeal. Here is your chance to find out all you ever wanted to know about silent film, but never dared ask.11.00 The Golden Butterfly/Der Goldene Schmetterling (Arts Picturehouse – Screen 3)

The final of our P.G. Wodehouse silent film adaptations is an altogether different affair from his golfing tales and this time, directed by the legendary Michael Curtiz before his migration to Hollywood. This is the story of a young restaurant cashier (Damita) who longs to be a dancer and each evening after work, she heads off to practice. One day she meets a handsome impresario who promises to make her a star, so she abandons her job and the boss who has fallen in love with her. But things go horribly wrong when an accident at the London Coliseum threatens to ruin her life. Some scenes were filmed on location in Cambridge.Dir: Michael Curtiz. With: Lily Damita, Jack Trevor, Hermann Leffler, Nils Asther. Germany 1926, 95mins

13.30 Short films from Desmet Collection at EYE – Netherlands (Arts Picturehouse – Screen 3)

A cornucopia of delights from the Desmet Collection held in the Netherlands Film Archive. This selection of British shorts includes Didums and the Bathing Machine in which the eponymous nightmare-child torments a hapless bather by stealing his clothes and the mad-cap Tilly girls in Tilly in a Boarding House. Also featuring are, A Canine Sherlock Holmes, Charley Smiler is Robbed, The Adventures of P.C.Sharpe and Picture Palace Pie Cans.Dir: various. Running time approx 80mins

13.30 Kipps: The Story of a Simple Soul (Emmanuel College)

A sensitive adaptation of H G Wells gentle comedy of social manners with a near perfect, and totally natural performance by George K Arthur (which was praised by Charlie Chaplin who attended the preview with H G Wells himself) in the lead role. Other things to enjoy are the nicely photographed seaside locations, the performance by the director’s wife, Edna Flugrath who plays the girl next door despite being clearly too old for the younger Ann, and the intriguing possibility that Josef Von Sternberg was involved with the production. He was certainly in London assisting Shaw around this time.Dir. Harold Shaw. With: George K Arthur, Edna Flugrath, Teddy Arundell. GB 1921, 88mins

15.30 The Annual Rachael Low Lecture – Britain could make it! (Arts Picturehouse – Screen 2)

Fifteen years of British Silents discoveries, and why we need to dig further into the mysterious ‘teens .When the British Silent Festival began fifteen years ago, very little was known or seen from the silent era in British production beyond Hitchcock. Now silent film is booming, and it’s clear that Britain had some outstanding talents, even though many of the films are lost. In this Rachael Low lecture, Ian Christie will be looking back at some of the festival’s discoveries, and taking a closer look at the period we still know least about – the mysterious ‘teens.

Ian Christie is a film historian, critic and curator, who teaches at Birkbeck College and regularly appears in television coverage of film history. He wrote the BBC Centenary of Cinema series, The Last Machine, presented by Terry Gilliam, and curated the BFI DVD of Robert Paul’s collected films.

17.30 The Ghost that Never Returns with the Dodge Brothers (West Road Concert Hall)

In an unnamed South American country, Jose Real is jailed for his activism at an oil refinery. Exasperated at his power and his popularity with the prison inmates, the authorities decide to eliminate him by promising him one day’s freedom and then sending an assassin to follow him. Together they ride trains and track across desert landscapes in a deadly game of cat and mouse which only one can survive. The movie looks and feels like a piece of Americana directed by Wim Wenders – and that is how the Dodge Brothers and Neil Brand have scored it. Following on from their triumphant score for ‘Beggars of Life’ the Dodges return to breathe rhythmic life into a classic of Soviet cinema full of moving characters and striking visuals, a movie you may never have heard of but, after seeing it, one you will never forget.“There are those rare moments in life where you are privileged to bear witness to a unique event, this, for me was one of them. Should they saddle up and recreate this triumph at any time in the future, then my advice to anyone, is buy your ticket early.”

Dir: Abram Room; With B. Ferdinandov, Olga Zhizneva, Maksim Stralikh. USSR 1929. Performance will last approx 80mins.

20.30 Highlights of the British Silent Film – Closing Event (The Varsity Hotel – Rooftop)

Over the past 14 years the British Silent Film Festival has uncovered a host of fascinating films almost unknown by the British public – this selection of feature films, actualities, animations, comedies, adverts local films, travelogues, nature and exploration film aims to inspire you to know more about the first 35 years of your film heritage. With live music from the best silent film accompanists in the world.

More information, as always, on the festival website.