Mabel May and the children of Piccanin village in The Picannins’ Christmas (1917), from http://www.vintagemedia.co.za

After rather too long a gap, we return to the Bioscope’s occasional series on national film histories – essentially a quick reference guide, with listings of online and offline resources for the researcher. So far we have covered Italy and China. And, inspired to a degree by my recent discovery of the guide to South African film and television, VintageMedia, our attention turns to a land not generally associated much with silent film at all, South Africa.

History

South African history, and therefore South African film history, is profoundly bound up with colonialisation, racial segregation and apartheid. The state enforced system of racial segregation was instituted in 1948 and ended only in 1994, but apartheid merely enshrined in statute an absolute state of privilege for the minority white population which had existed for a century or more. South African silent cinema was a minority cinema – white-owned, white-produced, white-performed (though not absolutely so) and exhibited for whites (again, not absolutely so). It was also a colonial cinema, similar to the situation in Australia, where local production was constrained by distance from Europe and America, by a lack of finance, and by a paucity of talent. It was a cinema on the margins.

Edna Flugrath and Holger Petersen in Der Voortrekkers (1916), from vintagemedia.co.za

When motion pictures first came to Johannesburg in 1895, South Africa did not exist as a country. There were the British colonies of Cape Colony and Natal, and the Boer republics of Transvaal and the Orange Free State. It was in 1910, following the upheavals of the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902 that the four combined as the Union of South Africa. Motion pictures came in 1895 in the same form as they did throughout the world, that is via the Edison Kinetoscope peepshow, which opened to the public on 19 April 1895 at Henwood’s Arcade in Johannesburg. American magician Carl Hertz brought projected film to South Africa when he first exhibited at the Empire Palace of Varieties, Johannesburg on 9 May 1896. Variety theatres quickly picked up on the new phenomenon, showing films mostly obtained via the Warwick Trading company in Britain, whose trademark projector the Bioscope became so fixed in the mind of South African patrons that it is still the common name for a cinema in South Africa over a century later.

The manager of the Empire Palace of Varieties, Edgar Hyman, became the leading figure in early South Africa film, obtaining a Bioscope cine-camera and becoming the first of a number of cameramen to film scenes from the Anglo-Boer War, an event of worldwide interest that ensured films from South Africa were in high demand. Joseph Rosenthal and William Kennedy-Laurie Dickson were aong the filmmakers whose war-front footage demonstrated the power (and the limitations) of the cinematograph as war reporter.

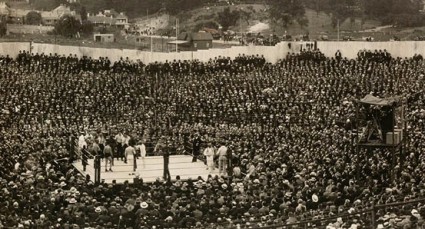

After the war and until the creation of the Union of South Africa, local production was minimal, mostly topicals of restricted interest, though British film companies, including Butcher’s and the Charles Urban Trading Company, filmed in the country. The first South African cinema opened in Durban in 1909, and such bioscopes spread rapidly throughout 1910, with the first cinema for ‘coloured people only’ reportedly appearing in Durban in December 1910. The issue of race came to the fore in 1910 with the banning of the film of the Jack Johnson-Jim Jeffries world heavyweight championship fight, because local authorities feared that its exhibition might cause racial unrest. Exhibitors in vain pointed out that in 1909 film of Johnson defeating the white Tommy Burns had not caused any social disruption, but the ban remained.

South Africa’s first fiction film, The Great Kimberley Diamond Robbery, was released in 1910. Made by the Springbok Film Company, it does not appear to have been a particularly disinguished production. The African Mirror newsreel, produced by I.W. Schlesinger African Films Trust, was a greater success, becoming the local agent for Pathé Frères. South Africa film production expanded in the teens through Schlesginger’s formation of African Film Productions in 1915. AFP brought in American talent in the form of Lorrimer Johnston and Harold Shaw to produce films with the potential for export to British and American markets.

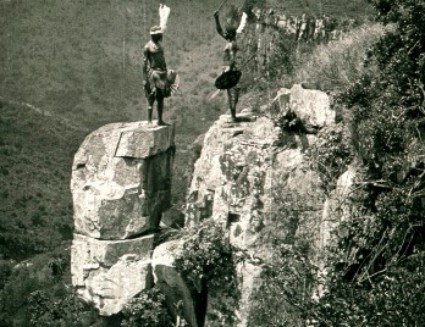

Shaw was the most notable filmmaker in South African silent cinema. He directed three feature films [correction, four – see comments], each starring his wife Edna Flugrath: Der Voortrekkers (1916, retelling the story of the Great Trek of the Boer people and the Battle of Blood River), The Rose of Rhodesia (1917, a drama about stolen diamonds with a strong underlying theme of racial understanding, made by Shaw’s own company) and a horse-raing drama, Thoroughbreds All (1919), the only title of the three now lost (almost no other South African silent fiction films survive). A fourth film, The Symbol of Sacrifice (1918), was to have been made by Shaw, but after disgreements with the film company it was directed by Dick Cruikshanks. The only other director of note was Joseph Albrecht, who was AFP’s main director into the 1930s.

British newsreel showing a screeing of Der Voortrekkers (as Winning a Continent) at the West End Cinema Theatre, London, in 1917, from www.britishpathe.com

Der Voortrekkers gained some overseas screenings under the title Winning a Continent, but African Film Productions struggled to find a market outside South Africa for its productions, with only King Solomon’s Mines (1918), made by British director H. Lisle Lucoque, and the lavish The Blue Lagoon (1923) being relative successes. The great popularity of American product, with vastly superior production values, meant that local productions such as Prester John (1920) and The Man Who Was Afraid (1920) struggled to find audiences even in South Africa. AFP produced over forty fiction films between 1916 and 1924, before turning largely to documentary and newsreel work, South African fiction film production effectively disappearing until the talkie era.

South African silent cinema was white-produced for white audiences, but there were few South African films that did not feature the black population in one form or another. Inevitably such roles depicted the native population as either threatening or compliant, with Harold Shaw’s boldly inclusive The Rose of Rhodesia only able to stand out because it was an independent production (in every sense). Black performers appeared as tribes imperilling whites in gung-ho dramas of imperialist adventure such as King Solomon’s Mines and its sequel Allan Quatermain, and as naive and obedient in sentimental productions such as The Piccanins Christmas (1917). There were a few early AFP productions with all-black casts, notably the Zulutown Comedies series of slapstick shorts from 1917, performed by the Zulutown Players (though these made for white audiences). Zulu actor Goba starred in one of AFP’s first productions, A Zulu’s Devotion (1916) and in several productions thereafter.

Director Dick Cruickshanks (centre) with the Zulutown Players, from Screening the Past

Little now survives of South African silent film production, but scholarly interest has grown following the recent discovery of a print of The Rose of Rhodesia in the Netherlands, and through a rise in African film history studies generally, headed by such scholars as Jacqueline Maingard, Neil Parsons and James Burns. South Africa also boasts one of the most notable of all film histories, Thelma Gutsche’s truly epic The History and Social Significance of Motion Pictures in South Africa 1895-1940 (1972, but completed in 1946). South African film history is still trying to live up to it.

Notable filmmakers

Joseph Albrecht, Dick Cruickshanks, Henry Howse, Lorrimer Johnston, Norman Lee, Harold Shaw

Notable performers

Adele Fillis, Edna Flugrath, Goba, Mabel May, Marmaduke A. Wetherell, Grafton Williams

DVDs and online videos

- The Rose of Rhodesia (streaming, via Screening the Past website)

- The Symbol of Sacrifice (some scenes were included in the DVD Isandlwana, Zulu Battlefield but this seems to be no longer available; The Symbol of Sacrifice was also available from online pay service Kuduclub but this closed down in 2011)

- Der Voortekkers (DVD-R from Villon Films)

Publications

- Peter Davis, In Darkest Hollywood: Exploring the Jungles of Cinema’s South Africa (1996)

- Thelma Gutsche, The History and Social Significance of Motion Pictures in South Africa 1895-1940 (1972)

- Luke McKernan, The Boer War (1899-1902): Films in BFI Collections (1999) [BFI filmography, available as PDF]

- Jacqueline Maingard, South African National Cinema (2007)

- Keyan G. Tomaselli, The Cinema of Apartheid: Race and Class in South African Film (1988)

Archives and museums

- National Film, Video and Sound Archives (Pretoria)

Websites

- African Media Program (extensive database of films and videos on Africa, with variable information on some silent era productions)

- A History of the South African Film Industry 1895-1003 (useful timeline from South African History Online)

- Screening the Past (special issue on the online film studies journal on The Rose of Rhodesia ith rich material on silent era South African production in general)

- Vintage Media (useful site surveying South Africa film and television history, with authoritative descriptions of most South Africa silent fiction films)