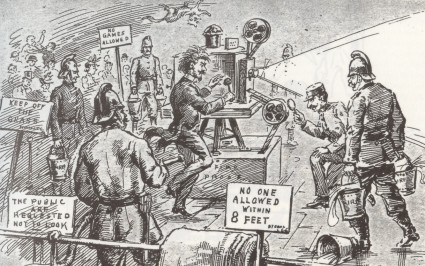

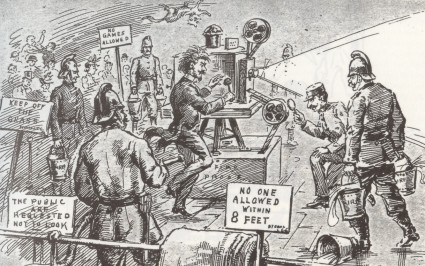

Cartoon parodying the alarm over the L.C.C.’s first regulations for film exhibition, from The Showman, 8 March 1901 (signed as being originally from The Photographic Dealer, 1898)

Back to the reminiscences of Edward G. Turner, the pioneer British film distributor. We’re still in the 1890s (we will move out of them eventually), and Turner and his partner J.D. Walker have their first encounter with the London County Council (L.C.C.), which had responsibility for the inner London area, including its public entertainments. The L.C.C. had become alarmed by the threat of fire presented by cinematograph exhibitions.

On November 8, 1897 I had an engagement at the Old Balham Baths, which I believe to-day is a permanent kinema. We had a notification from the L.C.C. that we could not show unless the apparatus and operator were enclosed in a fireproof enclosure.

This notification was delivered to us 48 hours befiore the show. So I worked all day and night in making a box out of corrugated iron. The dimensions were 4 ft. wide, 6 ft. long and 6 ft. high. The sizes were determined by the iron sheets.

This was the first operating-box ever made, and was used at Balham. This box again served as the model for practically every portable iron house, even to its dimensions, and the shutters which I originally made for this box became the standard article for this type of box.

Enter the L.C.C.

In those days the London County Council had no officers for dealing with kinematographic affairs. Somewhere about November they appointed a Mr. Vincent, who, I believe, was the head of the Chemistry Department in Villiers Street, Strand, as the officer responsbile for looking after these affairs. This gentleman inspected our box at Balham on the afternoon of the display, and told us that he would pass the box, subject to same being painted with asbestos paint inside and out.

Why this precaution I have never been able to understand, but the effects on Mr. Walker and myself were disastrous, as we had to work in this confined space, and before the end of the performance we had answered the riddle “Can a leopard change its spots?” We went in in black suits, and came out piebald, with most of the paint adhering to our clothes.

It was at Great Eastern Street that the first operating-box was made, and later improved by the addition of adjustable shutters.

The original box was fitted with a dead-man lever, i.e., the shutters had no means of being held up while the picture was being projected, except by a wire over a pulley, which was attached to a piece of wood about 15 in. long. One end of the wood rested on the floor, and the other, to which the wire was attached, would be about 6 in. off the floor.

The operator placed his foot upon the wood, which by its weight lay flat upon the floor, and the wire would automatically raise the shutter of the operating-box. If he took his foot off the lever, or fainted, or as soon as the pressure was removed from the lever down came the shutter. Later, we did away with the lever.

Soon we moved our offices to the second floor of Wrench’s premises at 50, Gray’s Inn Road, and after nine to twelve months we shifted our quarters to Nos. 77 and 78, High Holborn.

The Safety Shutter

When we had our office at 50, Gray’s Inn Road, we conceived the idea of automatic shutters to fall down between the light and the film. In those days we tested every machine that Wrench made, and, naturally, we took the idea to him, and in his workshop on the top floor, I believe, his mechanic worked out our idea and fitted the shutter, the opening and closing of same being worked by governor balls.

Wrench is Alfred Wrench. The long-established optical firm of J. Wrench & Sons became leading suppliers of cinematographic equipment at this time, and their offices at 50 Gray’s Inn Road housed a number of early film companies, including Will Barker’s Autoscope company, and later the Topical Film Company, as well as the eventual Wrench Film Company.

We then thought of covering in the space between the lensholder and the front of the film gate, working on the known law that combustion cannot take place without air, so that if the film fired in the gate, it went out, because there was not sufficient air left to support combustion, and thus was evolved the first fireproof gate, and we gave it to the world for nothing.

At this time we were doing business with Pat Collins (now an M.P.), Biddell Bros., the late George Green (of Glasgow), Haggar (of Wales), Dick Dooner, Jacob Studd and his sister, Hastings and Whyman, Ralph Pringle, Edison Thomas, Boscoe, all showmen; and, among lecturers, T.M. Paul, A.E. Pickard, A.H. Vidler, Waller Jeffs, Professor Wood, T.R. Woods, Baker (of Liverpool), and Lenton (of the Sherwood Film Agency), who bought his first outfit from me.

We, of course, had a number of competitors:- Joyce, of Oxford; McKenzie, of Edinburgh; Walker, of Edinburgh or Glasgow; Nobby Walker, of Bermondsey; F. Gent, of London; Jury, of Peckham (now Sir William); Brandon Medland; Matt Raymond and his lieutenant Rockett; Fowler and Ward, Ruffles Bioscope; Weisker, of Liverpool; Carter, of Leeds; Lens Bros., of Lancashire; Henderson, of Newcastle, and Gibbons (now Sir Walter). This list by no means exhausts the number.

Early Operators

Some of the operators I can remember who worked for us at this time are as follows:- Chas. Harper, C.H. Coles, W.M. Morgan, “Baby” Morgan, E.T. Williams, Jack Herbert, E. Mason (of Charrington’s, Mile End), J. Gardiner and his brother, George Palmer, W.W. Whitlock (now of gramophone fame), J. Nethercote (a school teacher), A. Malcolm, W. Walker, F. Hull, H. Luner, Joe Saw, Harry Last, F. Haward, Will Turner, T. Bosi (now of Herne Bay).

What an amazing list of names of those involved in the film business in the late 1890s. The showmen’s names are mostly familiar, being prominent fairground figures such as Ralph Pringle, Dick Dooner and William Haggar (soon to be a notable film producer). Edison Thomas is the notorious A.D. Thomas, a larger-than-life figure much associated with Mitchell and Kenyon. Waller Jeffs became a leading exhibitor in the Midlands, Matt Raymond, previously having worked for the Lumières, went on to become a prominent cinema owner (his assistant was Houghton Rockett), the Scottish Walker is William Walker, William Jury went on to become cinema’s first knight, while Walter Gibbons (also knighted) established the London Palladium. But many of those names are unknowns, and offer tantalising new avenues for research.

More from E.G. Turner in a few days’ time.