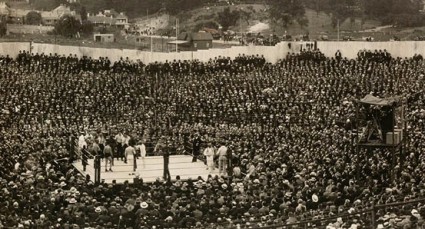

Jack Johnson knocks Jim Jeffries out of the ring at the climax of their world heavyweight bout at Reno, Nevada, on 4 July 1910. The referee is the fight’s promoter, Tex Rickard. Frame still from Sights and Scenes from the Johnson-Jeffries Fight (BFI National Archive)

I’m Jack Johnson. Heavyweight champion of the world.

I’m black. They never let me forget it.

I’m black all right. I’ll never let them forget it.

100 years ago, on 4 July 1910, two men met to contest the world heavyweight championship. One was James Jeffries, a former world champion brought back out of retirement to answer the call made by many in America to defend the white race. The other was the Afro-American Jack Johnson, the most iconic sportsman of the era, a man feared inside the ring for his tremendous power and outside it for the threat he seemed to pose to white society. The contest at Reno, Nevada was perhaps the most socially significant sporting event of the twentieth century. And of course the motion picture cameras were there.

Johnson lived much of his life in front of the camera. By the time he began fighting, sales of motion picture rights were a major source of revenue for those in the fight business, and every bout of significance was filmed, generally in its entirety, albeit semi-illegally given that prize fighting was prohibited in most American states. Films of Johnson’s fights were among the most significant of their age, to the point where legislation was created to contain them. Above all, Johnson was the first black person to be a leading film attraction – Dan Streible calls him “the first black movie star”. He helped change how America saw itself.

Arthur John Johnson, or Jack Johnson (1878-1946), was born in Galveston, Texas, the son of a former slave, and began his fighting career in 1897. He emerged as a major contender in the early 1900s, but the leading white boxers of the period mostly declined to fight against him, such was the racism endemic in the sport and American society generally. In particular he was effectively barred from any world heavyweight championship fight. There were other talented black boxers in Johnson’s time, notably Joe Jeannette, Sam McVey and Sam Langford, but they were mostly forced to fight among themselves for black-only championships. Johnson was unusual in his thirsting for the very top, avoiding the likes of Langford as much as possible in his search for the heavyweight crown.

Following the retirement of James J. Jeffries as world heavyweight champion in 1905, the championship and boxing in general went into decline. Two inadequate champions followed, Marvin Hart and Tommy Burns. Johnson became the beneficiary of the impoverished heavyweight scene, for the lacklustre Tommy Burns had failed to attract the crowds and money, and a new black champion, it was suggested, would attract controversy and a challenger to regain white supremacy. Johnson eventually hunted down Burns to Australia, and defeated him in Australia on 26 December 1908, becoming the first black world heavyweight champion. The fourteen-round fight was filmed by the British branch of Gaumont, though the Sydney police dramatically halted the filming and the fight in the final round to prevent the live and future audiences from witnessing any further humiliation for Burns. The film’s distribution around the world greatly helped revitalise interest in heavyweight boxing, while making the idea of a search for a white challenger to retake the crown something of an obsession for white American society. It also made Johnson a considerable film attraction.

The Johnson-Burns fight, Sydney, Australia, 26 December 1908, with the booth housing the motion picture cameras to the right. From Wikimedia Commons.

At first it was believed that a challenger would soon dispose of Johnson, but his easy defeats of such challengers as Stanley Ketchel (filmed for the Motion Picture Patents Company), ‘Philadelphia’ Jack O’Brien, Al Kaufman, and even the future film actor Victor McLaglen (not a title fight), created an atmosphere of panic and the very real search for a ‘white hope’ who would crush the disturbingly confident and powerful Johnson. Eventually former champion Jeffries was persuaded to come out of retirement to face him.

The build up to the fight of the century was tremendous, and the cinema was greatly involved. Films of both boxers in training were released, including one of a bulky and seemingly invincible Jeffries working on his ranch (Jeffries on his Ranch, made by the Yankee Film Co.). The fight itself took place on 4 July 1910 at Reno, Nevada, promoted by the larger-than-life Tex Rickard. Three film companies, Selig, Vitagraph and Lubin, representing the Motion Picture Patents Company, combined to organise the production and distribution of the fight film, under the one-off name of the J. & J. Company, with J. Stuart Blackton of Vitagraph supervising overall production and distribution. The cameras were set up in pride of place on a stand overlooking the ring, with no attempt at closer shots or other viewpoints, but with plenty of material shot prior to the event – enthusiastic crowds filling the street of Reno, both boxers in training, star fighters of times past and present (Abe Attell, ‘Philadelphia’ Jack O’Brien, Sam Langford, Jake Kilrain), and unique film of a portly John L. Sullivan, champion from another era, mock sparring with the first official world heavyweight champion, Jim Corbett (who made racial taunts at Johnson throughout the fight).

The fight lasted fifteen rounds, but was a foregone conclusion from round one, as Johnson humiliated a patently inferior Jeffries. That the fight lasted so long was no indication of Jeffries’ staying power; more likely it was an indication of Johnson’s awareness of the value of a full-length fight film. A film of a fifteen-round fight would command bigger audiences and greater revenue than a one-round knockout. It was commonly felt that Johnson had spun out the fight to increase its revenue (Rickard had promised $101,000 for the boxers, with 75% for the winner, and two-thirds of the movie rights), and this seems borne out by the evidence of the film itself. Johnson patently extends the contest beyond what was necessary, and can be seen taunting the hapless Jeffries during their numerous clinches. However, on the eve of the fight both Johnson and Jeffries had agreed to take lump sums for the movie profits rather than a percentage, so one might judge that Johnson’s motives were as much vengefulness as good business.

Jim Jeffries and Jack Johnson, from American Memory

But the most significant effect of the Johnson-Jeffries fight on the world of film came afterwards. The shock of Johnson’s victory terrified white America and thrilled the black community. Immediately the result was known there were racial conflicts throughout the country, resulting in many deaths and injuries. It was not only Johnson’s defeat of a white man, but his very public cockiness, his fondness for fast cars, fancy talk and fancy clothes, and above all his taste for white women (his various white wives were always prominent in newsreel footage of Johnson) compounded the fears. The existence of the film greatly added to the shock. Not only was one forced to read about the unspeakable Johnson becoming champion over the whites, but he could be appearing in your very own neighbourhood. The film of the fight had to be banned. With the racial violence that followed the fight as the primary excuse, and following heavy lobbying by such interest groups as the United Society of Christian Endeavor, the film was soon barred from many individual cities, and fifteen states went further by banning all prize fight films – it was assumed there would be other Johnson fights and other Johnson films, and so the states legislated against all boxing films rather than the specific cases of the Johnson-Jeffries film.

However, no immediate federal law was passed. Such legislation only arose when another Johnson fight film, that of his contest against ‘Fireman’ Jim Flynn on 4 July 1912, threatened further social unrest. Bills had already been introduced by the grossly racist Congressmen Representative Seaborn A. Rodenberry and Senator Furnifold Simmons to prohibit the interstate transportation of fight films, and on 31 July 1912 the legislation was passed. It was now a federal offence to transport fight films over State lines. This naturally had a severe effect on the production and distribution of boxing films, though it by no means stopped them. The ambiguous legislation, which was much challenged as it seemed directly to contradict reasonable commerce, did not necessarily prevent such films’ exhibition, and there was still a large audience keen to see such films, especially the Johnson-Willard contest of 1915 where the victorious Jess Willard finally proved to be the ‘white hope’ so many had been looking for.

One of the most striking attempts to by-pass the ban on interstate transportation occurred in 1916. The film in question was that of the Johnson-Willard fight; the company involved the Pantomimic Corporation (created by L. Lawrence Weber, the producer of the Johnson-Willard film). A motion picture camera was placed eight inches from the New York-Canada border, pointing north. On the Canadian side was placed a tent containing a box with an electric light. Past this was then run a positive of the Johnson-Willard film, which by means of a synchronising device was then photographed on the American side, and thus a duplicate negative (of doubtful quality) was produced. The whole extraordinary process was deliberately given wide publicity, but Pantomimic lost the ensuing court case, for having violated the spirit if not the letter of the law.

The law was a preposterous one, contrary to the basic rules of commerce and unashamedly racist in intent. It was widely violated throughout the 1920s, as the continued production of fight films indicates, and the Johnson ‘threat’ was in any case over. However, it was not until the late 1930s that calls for the legislation to be repealed were heard. Boxing was now seen to be popular among all classes, with a clear following among women, and the new, unthreatening black champion Joe Louis, modesty and courtesy personified, was the very model of what white America hoped to see. The Senate finally passed a bill permitting the interstate shipment of prize fight films on 13 June 1939.

Jack Johnson with one of his fast cars, from the Henry E. Winkler Collection of Boxing Photographs, University of Notre Dame

After the Willard fight, Johnson’s life went into decline. He had been sentenced to a year’s imprisonment in 1913 for violation of the anti-‘white slavery’ Mann Act (“transporting women across state lines for immoral purposes”) but skipped bail and fled to France, where he successfully defended his title against Frank Moran, the film of which was widely derided for its obvious spinning out of the fight to make a more commercial film offering. The Willard fight took place in Havana, Cuba, and he only returned to the USA to serve out his sentence in 1921, after spending time in Spain and Mexico. He carried on fighting in prison and following his release, and continued to appear before the motion picture cameras, though now in dramatic films, albeit very obscure titles made for the Afro-American community: As the World Rolls On (1921) and For His Mother’s Sake (1921) (Johnson had made at least one fiction film during his time in Spain).

Johnson kept on fighting until 1938, as well appearing on stage, refereeing fights, giving talks and making personal appearances. Always fond of fast cars and speeding, he died in a car crash in 1946.

From having been probably the most reviled man of his age, posthumously Johnson has undergone a considerable change in reputation. Always honoured by most fight fans for his boxing ability and his historical importance, he was increasingly held up as an example of black empowerment, starting with Howard Sackler’s 1967 play The Great White Hope, filmed in 1970 with James Earl Jones as the Johnson-like character Jack Jefferson. There then followed Bill Cayton’s Academy Award-nominated documentary Jack Johnson (1970) with its superb Miles Davis jazz score, which ends with the imposing words (spoken by Brock Peters) cited at the top of this post. Sympathetic biographies followed, notably Randy Roberts’ Papa Jack: Jack Johnson and the Era of White Hopes, and recently Geoffrey C. Ward’s book Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson, which was turned into a documentary by Ken Burns with another jazz soundtrack, this time by Wynton Marsalis. There is now a strong move in the US for Johnson’s 1913 conviction to be overturned, with Congress recommending in 2008 that he be granted a presidential pardon, a motion that received the unexpected support of Senator John McCain.

Finding out more

The PBS Unforgiveable Blackness website has extensive information on Jack Johnson and his times, including a special Flash feature on the Jeffries fight.

As noted above, the key biographies are Randy Roberts, Papa Jack: Jack Johnson and the Era of White Hopes, and Geoffrey C. Ward, Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson. On the Johnson-Jeffries fight in particular, see Robert Greenwood, Jack Johnson vs. James Jeffries: The Prize Fight of the Century; Reno, Nevada, July 4, 1910.

For the history of fight films in the silent era, with extensive information on Jack Johnson, there is the excellent Fight Pictures: A History of Boxing and Early Cinema, by Dan Streible, to which this post in much indebted, particularly the filmography. Acknowledgments also to Larry Richards, African American Films Through 1959: A Comprehensive, Illustrated Filmography.

Two essays cover the legislative back ground to the Johnson films: Barak Y. Orbach, ‘The Johnson-Jeffries Fight and Censorship of Black Supremacy‘, and Lee Grieveson, ‘Fighting Films: Race, morality and the governing of cinemas, 1912-1915’, in The Silent Cinema Reader, edited by Grieveson and Peter Kramer.

The Chronicling America site of digitised historic newspapers has a special section on the Johnson-Jeffries fight.

For celebratory centenary events, see www.johnsonjeffries2010.com.

In 2005 Jeffries-Johnson World’s Championship Boxing Contest (1910) was added to the National Film Registry as a work of “enduring significance to American culture”.

Parts of this post are taken from a long essay I wrote for Griffithiana in 1998 entitled ‘Sport and the Silent Screen’.

Filmography

1. Fight films

(Note: Fight films tend to be recorded under a variety of titles, but US copyright titles are given where available. Dates are the dates of the fights)

- [Jack Johnson v Ben Taylor] (GB, 31 July 1908, producer unknown)

- World’s Heavyweight Championship Pictures between Tommy Burns and Jack Johnson aka The Burns-Johnson Boxing Contest (GB/Australia, 26 December 1908, Gaumont)

- World Championship, Jack Johnson vs. Stanley Ketchell [sic] (USA, 16 October 1909, J.W. Coffroth)

- Jeffries-Johnson World’s Championship Boxing Contest, held at Reno, Nevada, July 4, 1910 (USA, 4 July 1910, J&J Company) [The cut down version held by the BFI is entitled Sights and Scenes from the Johnson-Jeffries Fight. There were also a number of re-enactment films made of the fight – see Streible, Fight Pictures]

- Jack Johnson vs. Jim Flynn Contest for Heavyweight Championship of the World (USA, 4 July 1912, Jack Curley/Miles Bros.)

- Johnson-Moran Fight / The Grand Boxing Match for the Heavyweight Championship of the World between Frank Moran and Jack Johnson (France? 27 June 1914)

- Willard-Johnson Boxing Match (USA, 5 April 1915, Pantomimic/L. Lawrence Weber) [Streible records a pirated version of the fight as well]

- Note: Denis Gifford’s British Film Catalogue lists a Jack Johnson v Bombardier Billy Wells fight film made in 1911 by Will Barker, but though the film was advertised the fight itself was abandoned and the film never made.

2. Fiction films

- Une aventure de Jack Johnson, champion de boxe toutes catégories du monde (France 1913)

- Fuerza y nobleza (Spain 1917-18, four-part serial)

- Black Thunderbolt (Spain 1917-18, released in USA in 1921 by A.A. Millman, 7 reels) [it is possible that this is the same film as Fuerza y nobleza]

- The Man in Ebony (USA 1918, T.H.B. Walker’s Colored Pictures, 3 reels) [uncertain credit, because Johnson did not live in the USA 1913-1919]

- As the World Rolls On (USA 1921, Andlauer Production Company, 7 reels)

- For His Mother’s Sake (USA 1922, Blackburn Velde Productions, 5-6 reels)

- Madison Sq. Garden (USA 1932, Paramount) [guest appearance]

3. Other films

(Note: Some of these titles probably reproduce material from earlier releases, such as the Kineto films of Johnson in training)

- Burns and Johnson Training (GB? 1909) [given by Streible, not by Gifford]

- Jack Johnson in Training/How Jack Johnson Trains (GB? 1909, Kineto) [given by Streible and BFI database, not by Gifford]

- Jack Johnson Training Pictures/Jack Johnson Training (GB? 1910, Kineto) [given by Streible, not by Gifford]

- Johnson Training for his Fight with Jeffries (USA 1910, Chicago Film Picture Co.)

- Mr Johnson Talks (USA 1910, American Cinephone Co.) [gramophone recording synchronised to film]

- How the Champion of the World Trains, Jack Johnson in Defence and Attack (GB 1911, Kineto) [given by Streible, not by Gifford. The title of the copy in the Nederlands Filmmuseum is Jack Johnson: Der Meister Boxer der Welt]

- Jack Johnson, Champion du Monde de Boxe (Poids Lourds) (France 1911) [newsreel]

- Jack Johnson Paying a Visit to the Manchester Docks (GB 1911) [newsreel]

- Jack Johnson and Jim Flynn Up-to-date (USA 1912, Johnson-Flynn Feature Film Co.)