Measurement is fundamental to film. In the early days of the medium, films were priced by the foot, with the content of little consequence unless it was coloured or featured a subject of particular importance, in which case the price per foot went up. The business was measured in how many feet of film were sold, competition was fiercest where cuts were made by one company in the price per foot of film, and as films grew longer they would still be measured in so many reels. Quantity overrode quality. Hold up a strip of film and you could use it as a tape measure – equidistant frames arranged in a straight line.

Films may be all digital now (or virtually so), but that has only increased their propensity towards measurement. There is duration, frame speed, file size, bit rate, and still that succession of frames that are fundamental to the nature of the time-based medium.

Then things get more complicated, because films comprise multiple shots. This was a puzzle for the earliest film producers, who started off believing that a different shot became a different film, to be catalogued, priced and sold separately. But art and the market started to demand that these shots be brought together. Films might now be measured in reels, but within those reels a complexity emerged, as the number of shots, and their length, started to vary according to the type of film or producer. This was not an issue as such for the producers of the period, but decades later it has become a matter of great interest to film scholars who would like to assess the art of film not just qualitatively but quantitively. Which is where cinemetrics comes in.

Cinemetrics graph for Battleship Potemkin, produced by Yuri Tsivian

Cinemetrics is the creation of Professor Yuri Tsivian of the University of Chicago. A renowned historian of early cinema (if his Early Cinema in Russia and its Cultural Reception isn’t on your bookshelf as yet, it should be), probably best known for introducing film scholarship to the marvels of pre-revolutionary Russian dramatic film, notably the work of Yevgenii Bauer. It was when Tsivian started doing an average shot analysis on the films of Bauer and his pupil Lev Kuleshov that Tsivian found evidence to show that “between 1917 and 1918 the cutting tempo of Russian films had jumped from the slowest to the fastest in the world”. What might previously have been intuited could, with patience, be demonstrated empiricially.

With patience, and some software, that is. Because Tsivian then did two extraordinary things. The first was (with computer scientist Gunars Civjans) in 2005 to build a software programme for measuring films; the second was to invite anyone in the world to take part and submit their data to a website – a model example of crowdsourcing in action.

Timing I think was my key thing. I was able to figure out the timing to close the gap between my opponent and myself and move back, and that was I think the key.

It is symptomatic of the imagination, as well as the playfulness, of Tsivian, that he should provide this quote from Chuck Norris on how he won six karate world titles. As Tsivian says, “much like martial arts, or like poetry and music, cinema is the art of timing”. Other scholars, notably David Bordwell and Barry Salt, has shown interest in average shot lengths as a means to measure film style, and Tsivian’s endeavour has demonstrated many scholars worldwide are similarly interested, and sufficiently dedicated to the cause to view and measure films (from any era, and of any kind) and submit the data online for all to study and share.

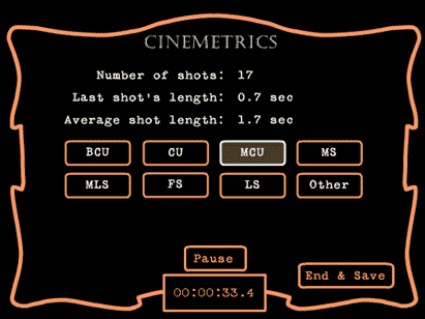

The Cinemetrics tool can be downloaded onto your PC or used online. The idea is that you then run your video and mark each change in shot with the click of a mouse on by hitting a keyboard button. This will then give you your data on the film’s length, number of shots and average shot length. You then upload the data to the Cinemetrics database, which produces graphs and publishes the data online for all to see. It’s that simple (an advanced option invites you to identify types of shot, such as close-up or medium shot). A more sophisticated tool, the Frame Accurate Cinemetrics Tool has recently been made available, for which you must rip a copy of the film you wish to analyse onto your hard drive (a tad contentious under some copyright regimes).

Video explaining how to use the new Frame Accurate Cinemetrics Tool (FACT)

Many have taken part, and there are many silent films that have been analyses. The database currently contains just over 10,000 titles, which can be sorted by date, country, director, submitter, average shot length (unsurprisingly the single shot Russian Ark comes out top), media shot length, and so forth. Many silent films are along them.

The Cinemetrics site hosts the database, software programme, articles (check out in particular Tsivian’s classic analysis of Intolerance), examples of Cinemetrics studies, a discussion board, and a lab section for comparing data. Most recently (and the reason for posting this now), a ‘conversations’ section has been added on film and statistics in which film scholars and statistical scientists come together to discuss their shared field arranged around particular themes.

The language of statistics is not one that appeals to most film viewers, and some of the debate may seem wilfully recherché. Talk of medians, means, datasets and outliers may seem to have little to do with the appreciation of film, reducing an art into a quantifiable commodity, just as those early film producers who only saw their product in terms of feet and reels.

But we cannot judge films by emotions alone, no matter how acutely attuned to artistic worth we may feel them to be. Data can quanitify what the eye may only sense or the heart feel. Of course there is more to film art than shot lengths, and new kinds of film analysis tools are starting to emerge which analyse action within and beyond the frame or shot (see, for example, the Gestus Project, which employs vector analysis; or Tim J. Smith’s acclaimed work on visual cognition, which maps where our eyes actually rove over the screen as opposed to where you think they might be looking). The important things in any sort of data analysis are relevance, consistency and range. The work of the cinemetricists is firmly relevant to how films are constructed, it is rigorously consistent in application, and the range of scholars worldwide who have conributed to this remarkable work enriches the data with every new contribution. Even if statistics leaves you cold, the ingenuity and dedication merit your admiration.

Acknowledgments to Nick Redfern of the Research into Film blog, a Cinemetrics contributor and film empiricist, whose blog alerted me to the new ‘conversations’ feature.

(Unfortunately the name ‘Cinemetrics’ has recently been adopted by graphic designer Frederic Brodbeck to create visualisations of films derived from their data. The results look beautiful, but do not quantify or analyse in the same way, and have no connection with Tsivian and Civjans’ Cinemetrics.)