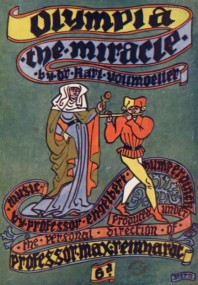

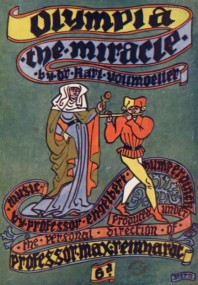

A newspaper illustration of the Olympia stage production of The Miracle

A few years ago – specifically in 2008 and 2009 – you may recall that we ran the Bioscope Festival of Lost Films. It was a droll conceit, using a blog to put on a festival of silent films that no longer existed. We described the films as if we were watching them (and yet not watching them), in London venues that once were cinemas but are no more, and with silent film musicians of the past to accompany said films. Regular Bioscopists got into the swing of things, even commenting on details of the clothes they had worn for the evening. All in all, it was a fun thing to research and write. You can find links to all of the films shown as part of the 2008 and 2009 festival on the Series page.

However, we pulled the plug on the festival thereafter, for three reasons. One, the festival took up too much time to research. Two, we received several requests from readers for information on these films, which they had imagined were lost and who couldn’t quite grasp what the concept of a lost film festival was supposed to imply. Thirdly, we learned after the 2009 festival that one of the films had in all probability survived. Great news for film; not such great news for a lost film festival, so we decided enough was enough.

We then waited for official notice of the film having been discovered before telling you about it, only to have discovered today that the news has been out for a quite a while now. Tsk tsk – the Bioscope should do better than that. So, belatedly, it is a pleasure to be able to tell you that Das Mirakel (Germany 1912) is not a lost film. It is held by the CNC film archive in France, and was screened last year as part of a Lubitsch retrospective (Ernest Lubitsch appears in a minor role in the film) and was reviewed – in French – on that excellent blog, Ann Harding’s Treasures. Alas, she reports that while the film is in prime condition, the direction is amateurish and the performances absurdly histrionic. This is both a surprise, given that the film was based on production by one of the greats of 20th Century visual theatre Max Reinhardt, while also not a surprise at all given the film’s peculiar production history.

As we related in the original post about the film, Das Mirakel came about when the British theatrical impresario C.B. Cochran was looking for an entertainment on a suitably grand scale to fill the vast arena of London’s Olympia. Cochran had seen Max Reinhardt’s production in Germany of Oedipus Rex and invited the great producer to devise a new epic production that would make best use of Olympia.

Reinhardt initially thought of recreating the Delhi Durbar ceremonies, held in India to mark the coronation of King George V in 1911. But instead he latched upon the idea of staging a medieval legend of a nun who escapes from her convent with a knight, experiencing assorted adventures and dangers, while at the convent a statue of the Virgin Mary miraculously comes to life and undertakes the nun’s duties. The major spectacle was provided by the drama’s cathedral setting, not to mention 1,000 performers, 2,000 costumes, 500 choristers, 25 horses, an orchestra of 2,000 and assorted examples of ingenious stage mechanics (see programme, left, from http://www.vam.ac.uk/users/node/9028). Given the distance between the audience and the action, the drama was presented in dumbshow (apart from the choir). The drama was written by Karl Vollmöller, with music composed by Engelbert Humperdink.

The Miracle, as it was known, was every bit the stage sensation that Cochran hoped it would be, with London audiences being overawed by its dramatic scale and its sentimental religosity when it opened over Christmas 1911. But where things get odd is when it comes to the film – or rather films – made of The Miracle. A film of The Miracle apears to have been an afterthought – a quick cash-in on the stage production’s popularity, at a time before Reinhardt gave any serious consideration of the possibilities of cinema (he would of course go on to produce a the classic Warners 1935 film A Midsummer Night’s Dream). It was originally reported that the film was to be made in London, but production instead moved to Austria, with producer Joseph Menchen and scenarist Michel Carré who was probably also the film’s director. Max Reinhardt himself seems to have had little to do with the film’s actual production. The oddness came with the camera operators and leading actress. The operators were the brothers William and Harold Jeapes, owner and chief cameraman at the Topical Budget newsreel. How they got the call to make the film is a mystery, but it was a hurried appointment, as William Jeapes later recounted:

In the first place, I may say that my own connection with the undertaking commenced just about twenty-four hours before I actually entered upon it, so you can imagine that there wasn’t much time for preparation. I received and accepted the request that I should take on the business, grabbed camera, films and baggage; caught the first train that was available, and, in almost less time than it takes to tell (as the novelists say) I was starting on the first preliminaries with Professor Reinhardt and M. Michel Carré (who adapted the play for the camera), near Vienna.

I left London on September 21st, and I returned on October 15th. During that time we were working regularly from the early morning until about 3 o’clock in the afternoon, at which hour it was necessary for the company to start back for Vienna, where ‘The Miracle’ was being played nightly – at the Rotunda. We did nothing on Sundays.

Jeapes and Jeapes were able newsreel operators, but were the last people you would have thought of to film a dramatic production, still less one so dependent on plausible illusion and a sense of scale. Odder still was that the key part of the Nun did not go to anyone from Reinhardt’s German production of the play, but instead went to an English actress without any film pedigree (or much of a stage one), Florence Winston. And she was Mrs William Jeapes. Other performers included Maria Carmi as The Madonna, Douglas Payne as The Knight, Ernst Matray as Spielmann, and somewhere in the background Ernst Lubitsch. All in all, a rum do.

As we wrote in 2009, the film received mixed reviews. Variety was dumbstruck, finding the film to be one of the wonders of its age:

The ‘Miracle’, reproduced from the wonderful Reinhardt pantomime of the same name presented at the London Olympia, is probably the finest exhibition of the “Celluloid drama” ever conceived. In some respects it is superior to the original pantomime spectacle, in that the paths of the performers – or characters – may be followed more minutely and with greater detail than is possible in the original, due to the possibility of showing the scenic progression with the unfolding of the plot … The whole presentment is remarkably impressive in general effect, the pictures so beautifully to resemble natural colors, the scenes so plentifully interspersed with captions announcing the progress of the tale, and finally the awakening to a realization that it was all a ghastly, enervating “dream”, is extraordinarily vivid. No spoken play could be more so.

The film’s lavish presentaton at special venues, with coloured print, a cathedral-like proscenium, organ, large choir and even incense wafting over the audience appears to have blinded some reviewers to the film’s actual shortcomings. The Bioscope (our favourite film trade paper) was more clear-sighted:

The whole play seems to have been adapted for the camera with only the most cursory regard for the latter’s possibilities and limitations. It has been forgotten that a scene viewed through an artifical glass lens is a very different thing from the same scene viewed in actuality by the naked eye … In the scenes showing the cathedral’s interior the stage is too deep, with the result that the players are constantly out of proportion with each other, and swell from midgets to giants in a fashion which is almost ludicrous as they move “down stage”.

Confusingly, there was a rival Miracle film, produced in Germany at the same time, which claimed that it was based on the legend rather than Vollmöller’s drama, to get round any copyright claim. It was also called Das Mirakel or Alte Legende – Eine Das Marienwunder, but in the UK it was marketed as Sister Beatrix. Produced by Continental-Kunstfilm GmbH in 1912, it was written and directed by Mime Misu, and is – we are fairly confident in stating – a lost film.

You can find details of the extant Das Mirakel on the CNC database. They credit the direction to Michael Carré and Max Reinhardt, but we doubt that Reinhardt had much to do with the film beyond initial negotiations (William Jeapes does at least note Reinhardt’s presence in Austria at the time of filming). Ann Harding’s Treasures’ review describes watching the hour-long film today as sheer torture, with acting styles of the flailing arm variety, no sense of composition or narrative, and a camera bolted to the floor simply recording theatre. She notes that a very much better film from the same source material exists, Jacques de Baroncelli’s La Légende de Soeur Béatrix (1923).

For all that, it would be good to have a chance to see Das Mirakel one day, just to get a sense of what so moved the variety reviewer. All it would need is a cathedral setting, an organ, a fair-sized choir and some incense. And every lost film found must be a cause for rejoicing, even if the story behind the film is of somewhat greater interest than the film itself. It is good to hae been wrong.