USA 1923

Director: John Griffith Wray

Production company: Thomas H. Ince Corporation

Director of photography: Henry Sharp

Script: C. Gardner Sullivan

Cast: Mrs Wallace Reid (Ethel MacFarland), James Kirkwood (Alan MacFarland), Bessie Love (Mary Finnegan), George Hackathorne (Jimmy Brown), Claire McDowell (Mrs Brown), Robert McKim (Dr Hillman), Harry Northrup (Steve Stone), Victory Bateman (Mrs Finnegan), Eric Mayne (Dr Blake), Otto Hoffman (Harris), Philip Sleeman (Dunn), George Clark (The Baby), Lucille Ricksen (Ginger Smith), George E. Cryer (A city official), Dr R.B. von Kleinsmid (An educator), Benjamin Bledsoe (A jurist), Louis D. Oaks (A police official), Martha Nelson McCan (A civic leader), Mrs Chester Ashley (A civic leader), John P. Carter (A civic leader), Mrs Charles F. Gray (A civic leader), Dr L. M. Powers (A health authority), Brig. C. R. Boyd (Salvation Army worker)

7,215 feet

Distributed by Film Booking Offices of America

Mrs Wallace Reid and Bessie Love (right), in Human Wreckage

Ladies and gentlemen, good evening, and welcome to the third screening of the Bioscope Festival of Lost Films. Today we find ourselves at the Casino de Paris in London’s Oxford Street. This small but fine building, which first opened its doors on 18 September 1909, seats just 175 of you. The venue has been chosen for its select nature, as only an invited and carefully vetted audience could be allowed in to see this evening’s sensational production which – as you will know – has been banned by the British Board of Film Censors. It is only under special licence from the London County Council that we are able to show it to you at all. The music comes from that legend among silent film pianists, Mr Arthur Dulay (round of applause).

What is also special about this evening’s main film is that it is to be shown in the presence of its principal performer, Dorothy Davenport, previously a popular film actress but now perhaps best known to you all as Mrs Wallace Reid (murmurs of sympathy). For it was the unfortunate death of her husband, the much-loved Wallace Reid, as the result of a wretched morphine addiction, that led her to produce Human Wreckage, and she has been tireless in presenting the film herself at its screenings across America. She is in this country to promote the film’s serious message, and we welcome her (warm and prolonged applause).

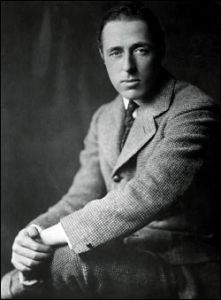

The history of Wallace Reid you will know well. The highly popular American star of such popular films as The Affairs of Anatol and Forever, became addicted to morphine, it is said after he suffered injuries in a railroad crash in 1919, while making The Valley of the Giants. What was at first medical expediency became an increasing habit, to the extent that it is believed that Wallace had morphine administered to him by a doctor at Famous Players-Lasky studios, to ensure that he could complete the many motion pictures that were demanded of such a popular star (expressions of shock and dismay). Many among you will recall the apathetic look that Wallace bore in his later pictures – only now do we know why! His death came on 18 January 1923, aged just thirty-one (deathly silence).

Human Wreckage is not the story of Wallace Reid. Instead it is a product of Mrs Wallace Reid’s determination, following her husband’s death, to campaign against the evils of drug pedling and addiction. Of course, its theme of drug addiction runs against the normal American censorship codes, but the picture’s serious intent has seen it gain a special dispensation from Mr Will Hays, and it was made under the guidance of the Los Angeles Anti-Narcotic League. You will have noted the various civic and health figures included in the cast (murmurs of approval).

Bessie Love as Mary Finnegan in Human Wreckage

The film tells of the evils of drug addiction as they affect several people. Jimmy Brown, a heroin addict, is arrested by the police but successfully defended in court by attorney Alan MacFarland. Jimmy is sent to hospital (where he endures the pains of withdrawal symptoms), while MacFarland, exhausted by pressure of work, is offered morphine by a friend. He gradually becomes addicted. Meanwhile his wife, Ethel, notices that a young girl, Mary Finnegan, living in the same tenement as Jimmy’s mother, is injecting herself with morphine. She is also putting morphine onto her breast to quieten the baby she is nursing. Mary tries to kill herself, but ends up in hospital and separated from her baby. Alan MacFarland is hired by Steve Stone, who is his own dealer, and manages to keep him out of jail. Ethel is unable to save her husband from his addiction, but then he discovers that despair has apparently led her to her own drug addiction, and this brings him to a shocked realisation of what he has put her through. Her ruse works, and he gives up morphine. Jimmy Brown takes Steve Stone on a mad taxi drive through the city, and both are killed in a crash. The film concludes with a plea from the MacFarlands for stronger laws to confront the evil of drugs.

The film has caused a sensation in the United States. Those uncertain about the film’s motives have been shaken by its sincerity and the power of its telling. Mrs Reid herself has been tireless in promoting the film, often introducing it herself, and using her profits to support the Wallace Reid Foundation Sanatorium, as well as establishing her own film production company (warm applause). It is no cheaply-made exposé; instead it has been handsomely produced by the Thomas Ince Corporation, and boasts some remarkable sets inspired by The Cabinet of Dr Caligari for one fantastical sequence. The producers’ confidence has been rewarded by the film’s noted financial success in America.

Here in Britain, where the American context of the story means less, the censors have been less accommodating. Our BBFC rejected the film in January 1924. Mrs Reid has organised some screenings for private individuals – our screening this evening is one of these – but this seems to have shocked the BBFC still further. The chief censor, Mr J. Brooke Wilkinson, has gone on to say:

There have been few, if any, films submitted to the Board since its inception which the examiners look upon as more dangerous than this film ‘human wreckage,’ and we see no possibility of altering it so as to make it suitable for public exhibition in this country.

And so it remains banned, and unseen (cries of ‘shame’).

The lost short accompanying our main feature is Dorian Gray (1913), also known as The Picture of Dorian Gray. How bitterly ironic it is that the young Wallace Reid should have starred in this film, playing Oscar Wilde’s seemingly unblemished young man, whose true, corrupted nature is revealed through a deteriorating portrait of him. The film was directed by Phillips Smalley and written by his talented wife Lois Weber, both of whom also appear in the film. It was made by the New York Motion Picture Corporation.

This has been a harrowing evening. We thank you all for you attention, and particularly to Mrs Reid for having graced us with her presence (loud applause). Tomorrow we will move around the corner to the Cambridge Circus Cinematograph Theatre, for a compelling Anglo-German production. Do join us.