Image of Buster Keaton from the Giornate del Cinema Muto’s trailer, animated by Richard Williams

We have reached day six of our reports on the 2011 Pordenone silent film festival (Thursday October 6th for those of you taking notes), and our undercover reporter The Mysterious X is showing no signs of flagging as he enters the Teatro Verdi once more…

Crumbs, Thursday already … in at 9.00am for a Disney short, Tommy Tucker’s Tooth (USA 1922) a semi-animated children’s instructional on dental hygiene. Neatly done, but the main point of interest now is that the healthily-grown kid with the good teeth of 1922 would today be being filmed at an obesity clinic, with a stern voiceover …

Then Klostret I Sendomir (The Secret of the Monastery) (Sweden 1920), a Victor Sjöström costume drama, part of The Canon Revisited strand. An elderly penitent monk tells a pair of guests the tale of the monastery’s foundation, by an Earl who discovers the betrayal of his wife’s adultery with her own cousin, and that his beloved son was not actually his. Confronting her, she initially deflects the affair onto her maid, before being given a choice; either she kills the kid, or she dies. Unexpectedly, she goes to do just that, but the Earl stops her at the last second; not doing so was her last chance of redemption, she is told, and she is duly despatched with the same dagger she was going to use. The son (who had already survived an earlier attempt at defenestration by the Earl) is taken to a woodcutter with some funds, and we are told the Earl sells up and founds the monastery. There is then a twist ending, that you can see coming from about five minutes from the start of the film.

It’s a competent enough film, but not vintage Sjöström. The actresses playing the countess and her maid were excellent, and stole the film despite – or perhaps because – they were playing irredeemable characters.

Tragedy of a different kind followed; the newly restored The Great White Silence (UK 1924) presented with live piano from Gabriel Thibaudeau, as opposed to the modern and not uncontroversial score on the BFI release (which I think is fine, personally). Gabriel, class act that he is, did a fabulous job on it.

Herbert Ponting’s documentary account of the doomed 1910-12 Scott Antarctic expedition looks stunning on the big screen – and despite being out commercially it drew a large and appreciative house. And the end is no less affecting for knowing it all in advance. It’s only now I’m wondering quite how the endtitles with their “Dulce et Decorum est” message would have played to the 1924 audiences, then fully aware of the futility of WW1, and not just the carnage.

Sound film!!! Sound on film at that … but from 1922, and Denmark, the experiments of pioneer Sven Berglund (Tonaufnahmen Berglund), who had demonstrated synchronised sound-on-film using two strips of 35mm the year before.

These were presented visually, multiple vertical lines varying in thickness with the volume, I assumed, looking like something from Len Lye; while the sound, read by laser in a lab and re-recorded on to the now-standard format, played out. As the film progressed we hear distant voices, distant music, until eventually, and very clearly, we get an English (American?) male voice reciting The Lord’s Prayer. For ’22, very impressive.

As was an unscheduled re-screening of Le Voyage dans la lune (France 1902) with a more traditional piano accompaniment from Donald Sosin. Yep, that was much more like it. (Take your word for it. – Ed.)

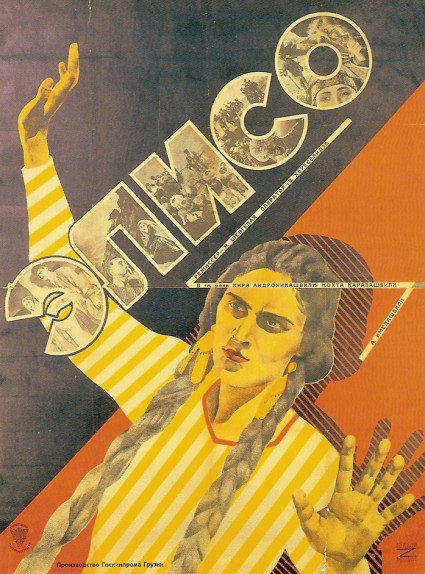

Poster for Eliso(USSR 1928), from http://www.cinematurkey.com

After lunch, and in for Eliso (Georgia SSR 1928), the day’s Georgian film; and the best of all of a very good bunch. Set again amongst the peoples of the high, remote mountains, but this time during the Tsarist era, this was a tale of love against religious divides, of cultural identity (positively – this was two years before Khabarda) as well as an element of “This is how bad it used to be”.

During a period of Russian expansionism a Moslem Chechen village is being deported en masse to Turkey to make way for Kazakhs; the scion of a nearby Christian village, in love with a Moslem girl, offers to help; the decision was a corrupt one. After a neat swordplay sequence worthy of Doug Sr. himself, our hero forces the general to cancel the deportation – but it has already started, after an ambitious couple tricked the village, into signing a petition for deportation thinking they were doing the opposite. The hero’s Moslem girlfriend is sent back from the caravan to burn their old village, to deprive the Kazakhs of its free use, nearly killing him in the process, as he was searching for her there. Back with the villagers, a woman dies in childbirth; this starts a a state of mourning, exacerbated by their miserable situation. Then a remarkable thing, and a remarkable sequence, happens. The village leader, elderly but striking and dignified, starts to dance: I read it as as a moment of supreme defiance; we have lost everything except what we can carry, and our culture, our identity. And we dance.

Slowly, very slowly, the tearing of hair stops. They watch him. A musician starts playing; hands are clapped; more dancers start. Gradually – five minutes perhaps – it becomes the most exhilarating dance sequence you’ve ever seen, young and old, male and female, hand-held camera roaming amongst them, the pace of the editing accelerating until the climax of sub-second flashed images. It actually surpasses the famous Coalhole sequence in Kean. All credit to the musicians; Günter Buchwald, Romano Todesco and Frank Bockius roared away, absolutely nailing the sequence. Please, someone, book this combination again; the topicality of the film, and the power the musicians bring to it, would wow any festival.

And straight into the second programme of Japanese animation; generally excellent, but not quite reaching the heights of Programme 1 … it mainly concerned the work of Noburi Ofuji, who used the cut-out technique applied to Chiyugami, the traditional Japanese printed paper, to create his comic characters. Pioneering, quirky and fun, also using sound-on-disc in the late silent period (or possibly animating to pre-existing records, I was none too clear) but they didn’t grab me as deeply. Others, from Ogino, were abstract patterns animated; very reminiscent of European avant-garde animation art of the thirties, the colour examples were, for want of a better word, particularly trippy. The final item was a 1937 Kodascope ‘How it’s Made’ short, Shiksai Manga No Dekiru Made (Japan 1937) showing cel animation in Japan. A good end to a fascinating strand … potentially the last Japanese strand as little remains that hasn’t been seen here over the years.

Despite my interest in early aviation I skipped the one-hour documentary on Santos-Dumont’s 50-second Mutoscope reel of him and Charles Rolls together, Santos Dumont Pré-cinesta? (Brazil 2010) … I expect Mr Urbanora to be aghast at such negligence, given his equal interest in the subject. (I am shocked. And saddened.- Ed.)

Evening, and a Disney, Jack the Giant Killer (USA 1923), before Fiaker nr. 13 (Fiacre No. 13) (Austria/Germany 1926), a Michael Kertesz/Curtiz film set in Paris despite its Austrian/German co-production status. This was a film with real charm, easily the best of the strand, and much more the sort of film to get you noticed by Hollywood; a melodramatic tale of the abandoned baby, daughter of a millionaire who doesn’t know she exists, but has been trying to find her now-dead mother. The girl grows up as the daughter of the horse-cab driver who found her. Apart from the charm, it features wonderful performances from the character actors, great atmosphere and excellent use of the Paris locations – it was highly reminiscent of Feyder classics like Crainquebille – my highest praise.

Thomas Meighan (right) in The Canadian (USA 1926), from http://www.silentfilmstillarchive.com

The last film was a real treat too; from perennially underrated William Beaudine, The Canadian (USA 1926); a drama, but with seriously good comic elements within. Set in the broad wheatfields of Alberta, its subject is the problems and practicalities of marriage in small disparate communities, where your nearest neighbour may be a day’s ride away. Thomas Meighan, his name above the title, is the foreman at a friend’s spread, but although he has his own smallholding sorted out, it’s not quite ready.

The farmer has a sister, coming over to live with him having lost the last of her English family; she is unused to both the more basic farm life, and to doing anything practical; when called upon to help out in the kitchen, she is not just clueless, but can’t help giving the impression that it’s all rather beneath her. After clashes – epic, and with some killer lines – with the sister-in-law played by the wonderful Dale Fuller, with the harvest in, and the foreman announcing his departure, she takes a surprising step; the sister offers to be his wife if he will take her away. They marry, and the tone of the film changes utterly. It becomes The Wind – without the wind. The parallels are extraordinary – and this is two years before the Sjöström classic. Here, the physical rejection of the husband is followed (we assume) by a rape perpetrated by the husband rather than a third party; there is a similar comic-relief cowhand, here played by a nearly young Charles Winninger; there is a crisis where hubby rides to the rescue in both films; and a similar Damascene conversion in the wives’ attitude when both farmers have raised funds to send them away.

The Canadian beat The Wind to the screen; one wonders which source novel was published first … and then we remember that The Wind‘s happy ending is not in the novel at all. The acting in The Canadian is solid, believable, but doesn’t have the grandeur of Gish and Hanson; but highly recommended if you’re interested in the prolific career of William Beaudine, who made great films in all sorts of genres, and yet doesn’t receive very much attention.

Sterling stuff once again from our sharp-eyed reporter. Look out soon for the report on day seven (the penultimate day), when we shall discover Lily Damita wearing not much more except jewellery, Eleonora Duse in a bonnet, Gene Gauniter in Ireland, and not one but two Betty Compsons.

Pordenone diary 2011 – day one

Pordenone diary 2011 – day two

Pordenone diary 2011 – day three

Pordenone diary 2011 – day four

Pordenone diary 2011 – day five

Pordenone diary 2011 – day seven

Pordenone diary 2011 – day eight