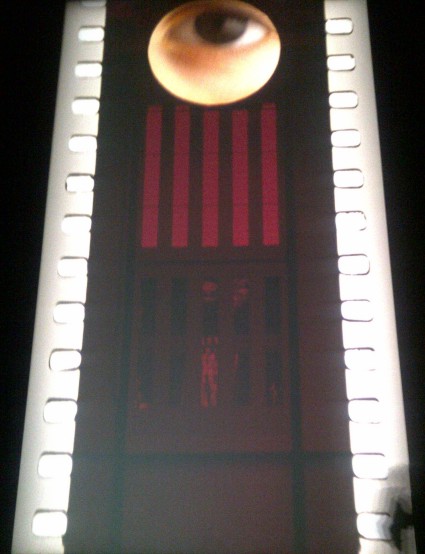

Tacita Dean’s artwork Film, projected in the Turbine Hall, Tate Modern, London

Will film die? Seen in one way, it never will: our cinematic history exists on celluloid and as long as there are viable film cameras and film, someone will be shooting it. Seen another way, film is already dead … what we see today is the after-life of a medium that has become increasingly marginalized in production and distribution of films and TV. Just as the last film camera was sold without headlines or fireworks, the end of film as a significant production and distribution medium will, one day soon, arrive, without fanfare.

Anyone with an interest in cinema can hardly have failed to pick up on the news that, apparently, film is dead. An article by Debra Kaufman for Creative Cow, ‘Film Fading to Black‘, from which the above quote comes, has had a huge impact, with many writing obituary columns for the medium in the face of the inexorable rise of digital. Kaufman’s specific impetus was the news that three major producers of film cameras, ARRI, Panavision and Aaton, have each over the past year decided to cease production of film cameras.

Kaufman’s article is not quite as brutal as the headlines might suggest. ARRI and the rest might not be producing new film cameras, but it is pointed out that there are plenty of film cameras out there already, which are presumably being kept to good use. There is no indication yet that Kodak and Fuji, the major producers of film stock, are to cease production, even though the demand for release prints is falling and the profit margins shrinking. 50% of American cinemas may now be digital, but that’s still 50% that aren’t, even if digital screens are being added at a rate of some 750 a month. Film archives still see film as the best preservation medium for film itself, with cold storage solutions for a medium already proven to last 100 years preferable to the huge uncertainties around digital, given the rapid obsolesence of file formats and technologies. Film hasn’t quite come to the end of the road yet.

But the end is in sight, isn’t it? Whatever the claims those of a traditional frame of mind make for the special visual qualities of film, it is on its way out. Nothing lasts forever, and film is after all just a carrier of images. If a more efficient, more flexible and – let’s face it – more appealing medium as far as the general public is concerned turns up, namely digital, then we bow to historical inevitability. Moving images may not ever look quite the same, as digital’s cleaness, brightness and rather antiseptic effect override film’s more textured and subtle qualities (though cinematographers are increasingly championing digital as new cameras promise deeper, richer qualities), but who in the end will notice? Things change, because things always change.

Certainly future audiences won’t miss anything in the switch from film to digital, and that’s not just because they will lack our experience of seeing film but because people change just the same as technologies change. They will grow up at ease with something else. So it is a rather odd experience that is provided at the moment by the installation Film at Tate Modern, which bemoans the disappearance of analogue. Film is an artwork by Tacita Dean. It takes the form of a giant projection (portrait shaped) on the far wall of the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern. Dean has devised the work as an expression of her concern at the threat to analogue film. It was shot, edited and is projected on film, and boasts an impressive list of production credits that is testimony to the craftmanship of film – grading, neg cutting, hand tinting, printing. As the exhibition notes state:

This is not a case of clinging to outmoded technology for nostalgia’s sake. As any practitioner will testify, digital and analogue formats are markedly different. The constraints and disciplines of working with a medium are essential to shaping the finished product. Photochemical film has its own distinctive texture and qualities, capturing light, colour, movement and depth in ways that digital cannot.

The eleven-minute film is abstract in form, being a succession of still and moving images bordered by perforations like a strip of film held vertically (as though passing through a projector). Images of buildings, trees, plants, water, circles, landscapes, rocks, but not people (apart from a fleeting figure passing by some stairs, and at one point a toe) play against and are overlaid with one another, someone with strong colour tinting reminiscent of the work of Len Lye. At a couple of points an eye appears in a circular frame that would appear to be a reference to G.A. Smith’s 1900 film Grandma’s Reading Glass, a key film in early film form. In most cases the images seem private to the artist and do not lend themselves to any particular interpretation except film itself.

It’s hypnotic stuff, but though plenty of people are watching it and children played happily in the light at the based of the screen, who among them really cares about film’s demise? Where are the lines of protestors outside cinemas, demanding that they see film as film? Where are the queues of unhappy customers returning their plasma screens to the shops, saying that the film experience is so much better? In truth, it’s not an issue that is going to concern anyone other than the afficionado and the specialist – and film/cinema is not the preserve of either of those. It is a popular medium, and the populace likes digital.

But that doesn’t mean the death of film, even after its main commercial life as over. Just as vinyl has survived the introduction of CD and audio files, so film is going to become the preserve of the select. Archives will still depend on it, though the rising costs of an increasingly rare medium (and rare skills able to maintain it) will mean higher access costs – if we want to see those films when they come out of cold storage so many years from now, we will have to pay handsomely for the privilege. Film buffs will still value it, and will collect prints and technologies required to show prints. They will sustain an aesthetic and cultural appreciation of film, and what will be exciting is when that appreciation is taken up by those who have grown up with digital but nevertheless look for something more in film. And artists, such as Tacita Dean, will continue to value it, for as long as it is available to them, for its plastic and particular qualities. Film is a canvas, after all.

The gloriously analogue Lomokino Movie Maker

And the first steps towards the second life of film as being made. I am greatful to Stephen Herbert for alerting me to the existence of Lomokino. Lomokino is a 35mm film camera for amateurs. Advertising itself as ‘gloriously analogue’, the camera allows you to shoot just 144 frames of film (curiously reminiscent of Twitter’s 140 characters) – and silent film at that. You need to find a lab able to process the film for you (which may prove tricky), then you can view your film via a LomoKinoScope viewer, or else scan it frame by frame, convert using iMovie, Windows Movie Maker or the like, and upload it to the Lomography site on Vimeo.

I’ve no idea whether this Austrian-based business is going to succeed, but its website certainly goes into a great deal of detail about how to make and present such films, with a large number of sample videos. There is a great range of cameras, film stock, accessories and bundles available on its online shop (including, I am intrigued to see, a Kinemacolor bundle). Do take a look – it feels like a cult in the making.

Sample Lomokino films

So film lives on, for the time being. It is important to the appreciation of silent cinema, because the entire genre (modern silents excepted) was produced using celluloid, whereas the history of sound cinema may run for centuries yet, of which just a few decades involved film as its primary medium. Yet silent cinema can also be rescued from historical oblivion by digital, given a new look and a new life, and that’s a cause for celebration. Silent films have a life beyond their temporary carriers. That they can change with the times is the best sign we have for their continued survival, and appreciation.