Time for a diversion. This spoof of The Empire Strikes Back has been doing the rounds recently. There have been ‘silent’ versions of Star Wars before now, but generally along the lines of speeded-up film and tinkly piano, good for half a laugh and nothing more. This is a little better. It takes the climax to the film and plays it more or less straight, with the original dialogue replayed as intertitles and the image itself impressively distressed to look like a battered, monochrome dupe (such as was seen by few in the silent era itself, of course, but hey you know what is meant). Anyway, it’s quite good, even a little moving in its way – and it could be just me, but isn’t Mark Hamill rather better as a silent film performer?

Category Archives: Modern silents

Loving Louise Brooks

‘Louise Brooks’ is one of the top search terms for people visiting the Bioscope, but so far there hasn’t been much here to satisfy them. Brooks is the silent film star for people who don’t otherwise like silent films. There is such a cult built around her that she seems to lie outside the film world that created her. Her appeal is so modern, so seemingly out of step, that she has ended up a class apart. It takes an effort of will to remember that she was a relatively minor American actress, considered difficult to work with and consequently with a rather patchy American film career, whose fame mostly lies with two German films made by G.W. Pabst, whose genius it was to exploit to the fullest that extraordinary uncompromising sexual quality she undoubtedly possessed.

The cult of Louise Brooks persists, and its latest manifestation is this intriguing French student film, to which Thomas Gladysz has drawn attention in a piece for the Huffington Post. It is made by the 18-year-old Sébastian Pesle, who stars in the 11-minute film as a filmmaker drawn more to the image of Louise Brooks on the screen (in Diary of a Lost Girl) than he is to his girlfriend (Malvina Desmarest), even when she dresses up as Brooks to try and capture his attention. It is shot as a silent film – that is, no one speaks (there are no intertitles), but there is natural sound (including a well-timed slap) and music. It’s a novel, thoughtful piece of work, well worth catching.

For more information on Brooks, there is the very useful Louise Brooks Society site and its accompanying blog, both maintained by Thomas Gladysz; an Italian site with information on all aspects of her career, Louise Brooks, Silent Film Star; her frank and exceptionally well written memoir Lulu in Hollywood (1982); a memorable essay, ‘The Girl With The Black Helmet’, on meeting Brooks towards the end of her life in Kenneth Tynan’s Show People; biographies by Peter Cowie and Barry Paris; and a thoughtful thread on the Nitrateville silent film disussion form commenting on her legacy.

And of course there are films – in particular look out for the Criterion edition of Pandora’s Box (which includes the Kenneth Tynan essay among its copious extras) and the Kino International edition of Diary of a Lost Girl. But catch Brooks in any of her few silent films, even in bit parts, and she lights up the screen in an extraordinary way, somehow aware of people watching her as much in 2010 as 1929. It would be hard to love Louise Brooks – all of the biographical evidence points to someone who was determinedly unlovable – but you cannot take your eyes off her. Which is what Loving Louise Brooks artfully captures.

Whom shall you telegram?

A minor diversion, courtesy of Boing Boing. It comes from The League of STEAM (Supernatural and Troublesome Ectoplasmic Apparition Management), a comedy troupe who present themselves as steampunk ghost-hunters (steampunk = modern technologies recast as Victorian). At any rate, it’s an entertaining take on Ghostbusters – though sadly the production budget didn’t run to any ghosts. You can find more of their videos at www.youtube.com/user/LeagueOfSTEAM.

Summer on the Southbank

BFI Southbank

We don’t normally highlight what takes place on a regular basis at film theatres and cinematheques, but looking at the August booklet for the BFI Southbank, it’s time to make an exception. It’s certainly a rich offering for silents and archival film in general.

The headline attraction is the UK premiere of the reconstructed and restored Metropolis (1927), now with an extra twenty-five minutes of footage, as documented on the Bioscope here, here and here. The screening takes place on 26 August, at 18:00.

The BFI is celebrating the 75th anniversary of its achive. Originally known as the National Film Library, it has subsequently been known as the National Film Archive, the National Film and Television Archive, BFI National Film and Television Archive, BFI Collections, BFI National Film and Television Archive once again, and now BFI National Archive. Passing over whatever insecurities have led to such a long-running identity crisis, you can help celebrate its 75th by attending its Long Live Film screenings, which are highlighting previously lost films that the Archive had particularly sought. Now, after decades hidden from view, you can see Britain’s answer to Fantomas, George Pearson’s Ultus and the Grey Lady (1916) plus other Ultus fragments (9 August, 18:00), Cecil Hepworth’s Helen of Four Gates (1920) (11 August, 18:10), Walter Forde’s What Next? (1928) (18 August, 18:20) and Ivor Novello and Mabel Poulton in The Constant Nymph (1928) (20 August, 18:10). Look out soon for BFI Most Wanted, a relaunched search for 75 lost British films, which is certain to include some key silent titles.

Among other attractions, look out for Alfred Hitchcock’s The Lodger (23 August 20:40); a programme of early archival treasures, A Night in Victorian and Edwardian London (4 August, 18:10); and Kenneth MacPherson’s experimental classic Borderline (1930), with Paul Robeson and H.D., introduced by film artist Stephen Dwoskin (5 August, 18:10). Collecting for Tomorrow (7 August, 13:30) is a discussion event, hosted by Dylan Cave, on the future of film collecting, which will include clips of recently acquired material including the work of modern silent filmmaker Martin Pickles (previously covered by the Bioscope).

Along the non-silent material, I must note the screenings of nitrate prints that are taking place at the BFI Southbank in July and August, also part of Long Live Film. Cellulose nitrate film stock stopped being employed in cinemas in 1952, and became the defining challenge for film archives in the latter half of the twentieth century. Nitrate film, owing to its high silver content, gavce the films on the screen a lustrous finish which is missing from safety film stock (let alone digital copies). However, because of the fire risks, a special licence is required to show nitrate film and the BFI has the only such licence in the UK. No silent nitrate films are on offer, more’s the pity, but over the two months you can see Fugitive Lady (1950), The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933), The Yearling (1946), Brighton Rock (1947), Anchors Aweigh (1945), The Ghost of St Michael’s (1941), Volga-Volga (1938) and Les Maudits (1946) as they were originally seen.

On the smaller screens at the BFI Southbank, the drop-in archive facility the Mediatheque has a special focus on British silents, including such titles as At the Villa Rose (1920), Comin’ Thro the Rye (1923), High Treason (1928), The Man Without Desire (1923) and Sweeney Todd (1928).

Finally there is the welcome return of the Ernest Lindgren Memorial Lecture. The Lecture, named after the National Film Archive’s esteemed founder curator, used to be a prestigious annual event at which a leading archivist or film historian would give a keynote presentation on the state of things. Sadly allowed to lapse in recent years, the Lecture returns on 24 August (18:10) with Paolo Cherchi Usai, Director of the Haghefilm Foundation. As film archivist of world renown and author of the provocative The Death of Cinema and co-editor of the essential text Film Curatorship: Archives, Museums and the Digital Marketplace, this should be a talk not to miss.

More information on all the above from the start of the July at the BFI Southbank site.

Pigeon: Impossible

The Bioscope scribes are currently toiling away at a long post which is taking ages to research (regulars may not realise that every post is first written out in long-hand with quills pens wielded by white-haired amanuenses working to the roughest of outline sketches, who then hand the parchment to a team of owl-eyed fact-checkers who lurk deep within the bowels of Bioscope Towers, seldom seeing the light of day. Only then is the hallowed text handed to yours truly, who heartlessly ignores most of it and instead types down whatever comes into his head).

While we wait, and while I head off to a conference and other such business for a couple of days, here’s a modern silent to entertain you, recommended by Bioscope regular Frederica. But is it a modern silent, or is it closer to a Tom and Jerry cartoon? Or should we look upon Tom and Jerry cartoons as model examples of silent filmmaking (Spike the dog aside)? You decide – or just enjoy a particularly ingenious and rib-tickling piece of modern animation.

3×3

This delightful short film doesn’t bill itself as being a silent film, but that’s what it is – exquisitely demonstrating wit and comic suspense through action, character and adroit choice of shot, and all wordlessly. It certainly has affinities with some of the comic masters of the silent era. The filmmaker is Nuno Rocha and his film, entitled 3×3 and made in 2009, has won awards at a number of festivals. It lasts just five minutes. Enjoy.

Louis

Louis is a new silent film about Louis Armstrong. It is directed by Dan Pritzker (a rock musician and the 246th richest man in America, no less), photographed by the great Vilmos Zsigmond, and stars Anthony Coleman, Jackie Earle Haley and Shanti Lowry. Being a silent film in form as well as spirit, it requires live musical accompaniment, and the film premieres in five US cities this August with music provided by trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, pianist Cecile Licad and a 10-piece all-star jazz ensemble. The music will be a mixture of a Marsalis score primarily comprising his own compositions, and Licad playing the music of 19th century American composer Louis Gottschalk. Marsalis says of the experience:

The idea of accompanying a silent film telling a mythical tale of a young Louis Armstrong was appealing to me. Of course, calling it a silent film is a misnomer – there will be plenty of music, and jazz is like a conversation between the players so there’ll be no shortage of dialogue.

The film’s website supplies this plot summary:

LOUIS is an homage to Louis Armstrong, Charlie Chaplin, beautiful women and the birth of American music. The grand Storyville bordellos, alleys and cemeteries of 1907 New Orleans provide a backdrop of lust, blood and magic for 6 year old Louis (Anthony Coleman) as he navigates the colorful intricacies of life in the city. Young Louis’s dreams of playing the trumpet are interrupted by a chance meeting with a beautiful and vulnerable girl named Grace (Lowry) and her baby, Jasmine. Haley, in a performance reminiscent of the great comic stars of the silent screen, plays the evil Judge Perry who is determined not to let Jasmine’s true heritage derail his candidacy for governor.

Pritzker was inspired to make Louis while he was working on a screenplay for a feature film about Buddy Bolden. He went to a screening of Chaplin’s City Lights with the Chicago Symphony, calling it “without a doubt the best movie experience I ever had”. He decided to produce a film that would follow on historically from where Bolden ended, and to make it in the early film style of Louis Armstrong’s childhood. His original idea to produce a short, black-and-white silent with Marsalis’ music to accompany Bolden, under the title The Great Observer, but the idea grew – and gained colour. Bolden, which is not a silent film, will be released in 2011.

Louis is playing at these American cities in August:

- August 25 – Symphony Center, Chicago

- August 26 – Max M. Fisher Music Center, Detroit

- August 28 – Strathmore Center, Bethesda, Md.

- August 30 – Apollo Theatre, Harlem, NYC

- August 31 – Keswick Theatre, Glenside (Philadelphia) Pa.

How I filmed the war

How I Filmed the War – trailer available from traileraddict.com

Has anyone come across a modern silent documentary? I suppose you could point to Godrey Reggio’s wordless Koyaanisqatsi (1982) and its successors, with their Philip Glass scores, but I’ve not come across an example of a documentary from today which emulates the style of documentaries from the silent era. Until now.

How I Filmed the War is a documentary by Yuval Sagiv, a graduate student of Toronto’s York University (the film is his thesis production). It received its premiere last week at Canada’s Hot Docs festival of documentary film. Its subject is Geoffrey Malins, the British cameraman who (with J.B. McDowell) filmed the 1916 documentary The Battle of the Somme, a feature-length account of the conflict from the British point of view produced by the British Topical Committee for War Films, a British film trade organisation formed with War Office support.

Malins went on to gain greater fame than his co-filmmaker because he wrote an account of his experiences, entitled How I Filmed the War (1920), which is something of a vainglorious work (and mentions McDowell not at all), but is nevertheless a lively and informative record that provides us with one of the best written records that we have of filming in the First World War.

Yuval Sagiv’s film adopts the title of Malins’ book and over 75 minutes analyses text and film in the form of a silent documentary, as the Hot Docs blurb explains:

One the most successful films ever made, The Battle of the Somme, shot and edited by Geoffrey H. Malins during the First World War, is brilliantly decoded in this riveting experimental doc that unravels fascinating secrets and manipulations. A compelling contemplation of the ownership of history plays out on intertitles taken from excerpts of Malins’s controversial autobiography juxtaposed with conflicting historical accounts and emotionally devastating clips from the original film. Dispatched to the front as Britain’s “Official Kinematographer,” Malins filmed from the muddy trenches to capture the valour and horror of “the big push” on July 1, 1916—a day that has become synonymous with the futility of war. The British alone suffered 58,000 casualties by nightfall. The rising tension in this fascinating deconstruction of propaganda, illusion, and “truth” in documentary is underscored by a haunting electro-ambient soundscape.

You can get some sense of the effect from the trailer to the film, which is available on traileraddict.com. Malins’ book is available on the Internet Archive, and was covered by a previous Bioscope post, while The Battle of the Somme itself has been made available on DVD by the Imperial War Museum (also covered by an earlier Bioscope post). There is a short biography of Malins on the IWM‘s site.

The Battle of the Somme itself is indeed arguably one of the most successful films ever made, at least in the UK – historian Nicholas Hiley (to whom thanks are due for alerting me to the new film) has calculated that the film was seen by some 20 million people, or half the population of the UK at that time, a degree of social impact for a screen entertainment that would go unmatched until the rise of television. It will be really interesting to see how How I Filmed the War tackles its tremendous subject – the trailer suggests a compelling interplay between original footage and words carefully selected from Malins’ book (with their original typeface and page number) to set up a stimulating counter-narrative. There’s an interesting review at Toronto Film Scene which describes a subtle, challenging work once one has got over the unusual technique and minimalist style. I hope that it makes it to a few other festivals.

Killruddery returns

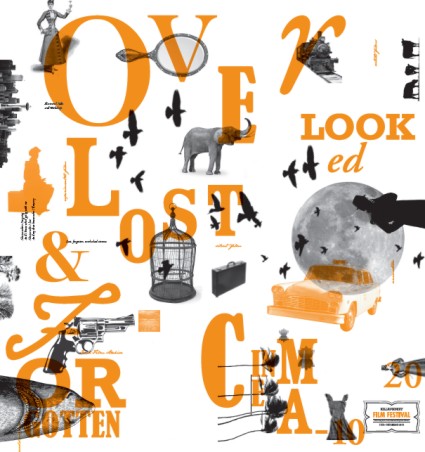

The Killruddery Film Festival has announced its 2010 programme. This excellent venture, now in its fourth year, is held in the delightful location of Killruddery House in Co. Wicklow, Ireland, close by Bray and a short journey from Dublin. To date the festival has been dedicated to silent films, but for this year they have introduced some sound films to what looks a well-rounded and effective programme. The theme of the festival, which runs 11-14 March, is Celebrating Lost, Overlooked & Forgotten Cinema. One might argue that not all of the titles on show fall into those categories, but every film screening is new to someone in the audience, so there are discoveries come what may. Here’s the line-up:

Thursday 11th March

Down Wicklow Way @ 6.15pm

Programme from the IFI Irish Film Archive, presented by Sunniva O’Flynn. With live musical accompaniment by Josh JohnstonA Cottage on Dartmoor (UK 1929 d. Anthony Asquith) @ 8.15pm

Introduced by Kevin Brownlow. With live musical accompaniment by Stephen HorneFriday 12th March

Los Angeles Plays Itself (US 2003 d. Thom Anderssen) @ 2pm

With live musical accompaniment by Stephen HorneBack Down Wicklow Way @ 6pm

More archive films presented by Sunniva O’FlynnThe New World (US 2005 d. Terence Malick) @ 7pm

Lucky Star (US 1929 d. Frank Borzage) @ 8pm

The Parallax View (US 1974 d. Alan Pakula) @ 10pm

Saturday 13th March

A Future Past @ 12am

Programme of science-fiction films presented Andrew Legge, including High Treason (UK 1929 d. Maurice Elvey)Children’s Shorts Programme @ 12.30am

Poil de Carrotte (France 1925 d. Julien Duvivier) @ 2pm

Sita Sings the Blues (US 1008 d. Nina Paley) @ 2.15pm

Talk: On the developing art of the video essay @ 4pm

Given by video artist Matt Zoller SeitzCity Girl (US 1930 d. F.W. Murnau) @ 4.15pm

Introduced by Kevin BrownlowChang (US 1927 d. Merian C. Copper /Ernest Schoedsack) @ 6pm

With live musical accompaniment by Stephen Horne. Introduced by Kevin BrownlowSeven Days to Noon (UK 1950 d. John and Roy Boulting) @ 6.15pm

Presented by John BoormanI Know Where I’m Going (UK 1945 d. Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger) @ 8.30pm

Sunday 14th March

Talk: Unknown Chaplin @ 12pm

Illustrated lecture given by Kevin BrownlowBritannica & other stories @ 1pm

Programme of artists’ films, including the work of John LathamIngeborg Holm (Sweden 1917 d. Victor Sjostrom) @ 2.15pm

Introduced by Charles Barr, with live music accompaniment by Stephen HorneBudawanny (Ireland 1987 d. Bob Quinn) @ 4pm

Modern silent film about a young priest (played by Donal McCann) who becomes romantically entangled with his housekeeperRed Dust (US 1932 d. Victor Fleming) @ 4.15pm

Introduced by Kevin BrownlowThe Patsy (US 1928 d. King Vidor) @ 6pm

Introduced by Kevin Brownlow, with live musical accompaniment by

Josh JohnstonGoddess/Devi (India 1960 d. Satyajit Ray) @ 6.15pm

Presented by Rebecca MillerThe Wind (US 1928 d. Victor Sjostrom) @ 8pm

With live musical accompaniment by Stephen Horne

Now that’s what I call an eclectic programme. Tickets are now on sale (you pay for individual screenings), and full details can be found on the festival site. Hope it does well.

Merry Christmas everyone

Festive greetings to one and all. Before I head off into the snowy wastes of Kent to spend a few days with the nearest and dearest, I present to you this rather charming home-made silent (by TheBrothersGrin) as a seasonal treat. Our heroine finds herself in peril of her life on the toy train tracks beneath the Christmas tree, but our hero comes to the rescue not once but twice. See you all in a few days’ time.