Letter from the American Foreign Service to MI5 seeking biographical information on Charlie Chaplin and evidence of communist affilation, from The National Archives, catalogue reference KV 2/3700

The National Archives in the UK holds the papers of British government departments, and releases these to the public after a period of 30 years (see the Bioscope guide to using TNA as research resource for film history). It releases previously embargoed papers at other times, and recently has been making available historical papers relating to MI5, the British counter-intelligence organisation whose very existence was officially a secret not so many years ago. Today’s release of a set of papers (available online) includes MI5’s dossier on Charlie Chaplin.

MI5 had no interest in Chaplin, and no reason to have one, until it was approached by the FBI in 1952 with the request that it seek out information on Chaplin’s birth and his supposed Communist sympathies. It was the height of the Cold War, and Chaplin had become a high-profile victim of the hysterical anti-Communist mania that swept through the United States in the late 40s and through most of the 1950s. Chaplin’s personal sympathies were clearly with the downtrodden, as his films demonstrated, but from 1942 onwards when he addressed a meeting of the American Committee for Russian War Relief with an enthusiastic ‘Comrades!’ and spoke at other events that supported from America’s war ally, he was viewed with increasing suspicion and distaste. That distaste had a lot to do with unsavoury details from his private life (the Joan Barry paternity suit, among other matters), and moral indignation combined with political paranoia to create an increasingly vicious hostility towards Chaplin, from the American press, broadcasters, religious bodies, politicians and government services.

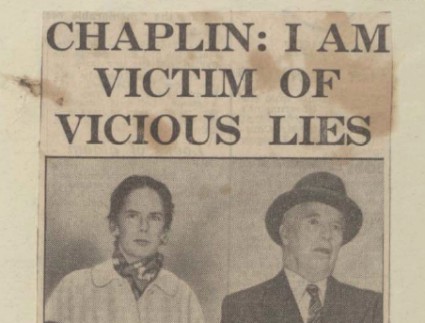

Clipping from the Daily Mail, 18 April 1953, in the National Archives files

By 1947, and the release of Monsieur Verdoux (the sour tone of which somehow accentuated the suspicions held against him) Chaplin was being openly accused of being a Communist sympathiser. His frank, reasoned responses to questions fired at him from all sides did not help his cause. After making Limelight Chaplin left America with his family for Britain, 17 September 1952. When at sea the news came through that the US Attorney General James McGranery had rescinded Chaplin’s re-entry permit, stating that Chaplin would he held if made any attempt to enter the United States once more. Chaplin had been exiled.

It was following this bombshell that the FBI wrote to MI5 seeking the dirt on Chaplin. It is fascinating to read the dossier that the British secret service compiled. It is a mixture of letters, telegrams, memos, newspaper cuttings and marginalia, as the issue was kicked around from department to department, with the British trying in vain to find any information to support the American allegations (which they considered from the outset as being “of very doubtful quality”).

Chaplin had no birth certificate – this was immediately suspicious. The Americans believed that he might not be British-born at all, but that he could have been born in France, and that his true name might be Israel Thornstein. The documents do not say from where the Americans got this preposterous intelligence, though there is indication that they were prepared to believe every bit of innuendo fed to them by informers, and any suggestion of Jewish origins presumably further confirmed Chaplin’s moral turpitude and political heresy. Chaplin did not have a birth certificate, in Britain or in France, but had they searched a little harder they would have found the young Charles Chaplin recorded in the London census returns of 1891 (aged 2) and 1901.

Ivor Montagu’s 1952 telegram to Chaplin, when Montagu was in Peking

The FBI also wanted evidence of Chaplin’s Communist sympathies, ideally of Party membership. It was said that there was an “unknown issue” of Pravda in which Chaplin was praised and a Chaplin film to be made in Russia was promised. MI5 searched diligently for the mysterious issue, and found nothing. The FBI wanted confirmation (note their confidence that the evidence was out there somewhere) of Chaplin’s “financial and/or cultural contributions to the Communist movement”. None was found. The nearest the MI5 got to it was a cheerful telegram sent to Chaplin by Ivor Montagu, filmmaker, writer, table tennis player, associate of Hitchcock and – as we now know – a Soviet spy. But the telegram was innocuous and MI5 did not pass it on to the Americans.

The search carried on in desultory fashion until 1958, at which point a MI5 memo concluded (with a dash of film criticism):

It is of some interest that when Chaplin was last in London in 1957 with this film A King in New York (a not very successful satire which featured ‘McCarthyism’), he was at some pains to avoid entanglement with the Russian Embassy here. He did not want to run the risk of political embarrassment. It may be that Chaplin is a Communist sympathiser but on the information before us he would appear to be no more than a ‘progressive’ or radical.

And that of course was the truth. The mild bewilderment of the British secret service faced with actual evidence as opposed to political dogma tells its own tale. The whole disgraceful saga did not properly come to an end until Chaplin was welcomed back to the United States in 1972 to collect an Honorary Academy Award.

The 112-page MI5 dossier is available from the National Archives website, where it can be downloaded for free for the next month.

But the question still remains – where on earth did the Americans find the name Israel Thornstein? (for the answer, see comments)