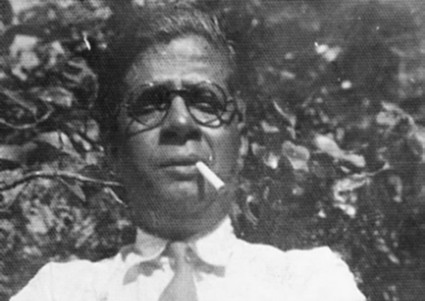

Niranjan Pal

The chances are that few people even with a good knowledge of silent films will have heard of Niranjan Pal, though you may have started to hear about his films. The release on DVD of the film A Throw of Dice (Prapancha Pash) (1929) has brought to our attention the three silent films on Indian themes directed by Franz Osten: The Light of Asia (Prem Sanyas) (1925), Shiraz (1928) and A Throw of Dice, whose production history and whose very existence strike a fascinating, almost jarring note in film history. Where and how did these non-Indian Indian films get made, and who was behind them? Well, the person behind them was, to large degree, Niranjan Pal.

Niranjan Pal (1889-1959) had a more than usually interesting life story for a filmmaker. His name has previously been best known to scholars of Indian nationalism and revolutionary politics in Britain. Born in Calcutta (Kolkata), he was the son of Indian nationalist leader Bipin Chandra Pal (right), and was brought up in culture dedicated to Indian self-determination and the overthrow of British imperial rule. Father and son came to London around 1908 when the father was invited by Pandit Shyamji Krishna Varma to help conduct pro-Indian freedom propaganda in Britain. Krishna Varma was the founder of the Indian Home Rule Society and the celebrated India House, a home for Indian students which became a hotbed of nationalist thinking, something which got it closely monitored by the British police. Bipin Chandra Pal was on the moderate side of the nationalist arguments, but his son was fired with revolutionary thinking, and was soon drawn into dangerous activity, as his autobiography recounts:

I was initiated into the work of preparing cyclostyled copies of formulae for manufacturing bombs. These were sent out to India by the hundreds, to addresses found in street directories. I learned that the formula had been secured, with great difficulty, from certain Spanish and Russian sources.

Pal’s father was alarmed by the route down which his son was going, particularly the admiration he had for freedom fighter Vinayak Damodar Savarkar with his advocacy of violent revoution. Pal’s Irish girlfriend of the time had close links with Irish republicanism and was violently opposed to all forms of British rule. Things became particularly dangerous following the 1909 assassination at the Imperial Institute in London of Sir William Hutt Curzon Wyllie by Madan Lal Dhingra, with whom Niranjan was familiar. Ironically, it was not so much the attempts by his father to moderate his son’s passions as British culture itself that started to mollify Niranjan Pal’s thinking. As his great-grandson Joyojeet Pal writes:

Pal and his Indian friends were deeply torn between their sense of loyalty to an Indian homeland, and a conflicted relationship with their colonial masters. The same Indians who were subjected to second-hand citizenship back in India, were treated as equals under British law … They would grow to view the Englishman in England very differently from how they saw the Englishman back in India.

Pal was introduced to London’s literary/intellectual elite, meeting Bernard Shaw and the Countess of Warwick, befriending the writer David Garnett, and being supported by the journalist W.T. Stead after his father was arrested back in India. He made the key discovery for him of the London theatre, delighting in the colourful productions of the West End stage, bridling at its occasional representation of Indian life, and wondering how he might bring about a change in perceptions through his pen.

Pal abandoned his medical studies and took to writing for the stage. He joined up with Kedar Nath Das Gupta’s Indian Art and Dramatic Society, which put on recitals and dramatic productions designed to promote Anglo-Indian relations. One of these was an adaptation by Pal of Sir Edwin Arnold’s celebrated narrative poem, The Light of Asia, on the life of the Buddha. Entitled Buddha, it ran at the Royal Court Theatre for a few days in February 1912. Pal also acted, in the small role of Devadatta. Pal then offered the script to a couple of British film studios. The Hepworth Manufacturing Company gave him the courtesy of a hearing, but said it was not for them. Barker Motion Photography merely laughed at him.

Such work was unpaid, and to keep body and soul together Pal undertook assorted menial posts in London stores while looking to make money, and reach a wider audience, by tackling motion pictures more assiduously. He undertook a correspondence course which guaranteed, for the sum of one pound, to turn the young man into a screenwriter. He continued writing to British film studios, only to be met by a growing pile of formulaic rejection letters. Finally, someone wrote back. It was Charles Urban (left), who wrote to say that Pal’s script was completely unfilmable and that he needed the experience of seeing how a film was made. So it was that Niranjan Pal was invited to the south London studios of the Natural Color Kinematograph Company, helping out with scene shifting while learning what he could of the film production process.

While there Pal befriended director Floyd Martin Thornton. He showed Thornton his script for The Light of Asia, Thornton took it to Urban, and Urban decided it would make a handsome subject for a major Kinemacolor production. Urban was at the height of his fame at this time, having triumphed with the Kinemacolor record of the Delhi Durbar celebrations held to mark the coronation of King George V, and an exotic, Indian-themed story must have seemed a natural choice for a Kinemacolor fiction film production. Pal continued at the studio, uncertain that Urban would be as good as his word, only to be stunned by the huge payment of £500 for his script from the handsomely generous Urban.

It would be interesting to consider how Anglo-Indian film history might have developed had the Kinemacolor version of The Light of Asia ever seen the light of day. Sadly the production never reachd even the early stages of production, as Urban’s Kinemacolor business collapsed in 1914 following a court case brought by rival colour film inventor William Friese-Greene, which decided that the patent on which Kinemacolor was based was invalid.

Floyd Martin Thornton however remained keen to work with Pal, and tried continually to raise the finance to film The Light of Asia. Thornton was able to film two Pal scripts, both with stories set in India. The feature-length The Faith of A Child (1915) was made for the obscure Lotus Feature Films, and The Vengeance of Allah (1915) for the Windsor Film Company in Catford (Pal’s memoirs talk about filming for the Kent Film Company, which must have been associated with Windsor in some way). Pal also made a documentary, the title of which he recalls was A Day in an Indian Military Depot (1916), filmed at Milford-on-Sea, which he successfully sold to distributor William Jury (possibly on behalf of the War Office Cinematograph Committee with which Jury was involved), though I have not been able to trace any information about it.

Post-war, Pal remained in Britain, determined to succeed with his pen. He was still associated with Thornton, and began work on an adaption of Ethel M. Dell’s novel The Lamp of the Desert for Stoll Picture Productions. It is evidence of the conflicting impulses with Pal that this person so ardent in his wish for Indian independence and anxious for understanding of Indian culture should keep turning to sources that pandered to what we now refer to as Orientalism (the depiction of the East by the West, essentially), in the case of Dell by someone who had never even been to India. Pal was taken on as scriptwiter and technical adviser, but it seems that his suggestion that palm trees were not to be found on the North West Frontier did not tally with Stoll’s ideas of how India ought to look, and he was dropped from the production (Stoll eventually released it in 1922, directed by Thornton).

Pal attempted to go into production for himself, with a film entitled The Tricks of Fate, but he seems to have been duped by some con-men. The film that was to have been directed by, written by and starring Niranjan Pal was unscreenable, and he lost a lot of money. Instead he found success on the stage, with his play The Goddess (1922), which was put on with an all-Indian cast, first at the Duke of York’s Theatre, then the Ambassador’s Theatre and then the Aldwych, running for sixty-six performances over six months in London before touring the provinces.

Tourists being introduced to India at the start of The Light of Asia, from http://memsaabstory.wordpress.com

Most significant for Pal’s future career was one of the perfomers in the cast of The Goddess, Himansu Rai. Rai formed an acting troupe, the Indian Players, and when efforts to stage The Goddess in India proved fruitless. Rai and Pal turned to the film industry, once again with the script for The Light of Asia. This time, with Rai’s greater drive and guile, they met with success, though not with a British studio but instead with German producer Peter Ostermayer, who agreed on a production at Berlin’s Emelka Studios, with location filming at Jaipur. Financing came from the Delhi-based Great Eastern Film Corporation. The director was Ostermayer’s brother, Franz Osten.

The Light of Asia, or Prem Sanyas, finally made it to the cinema screen as an Indo-German production in 1925. It told the story of Gautama (played by Himansu Rai), son of King Suddodhana, who leaves his sheltered existence to learn of the sorrows of the world, becoming a wandering teacher who brings Buddhism to the world. The cast was all Indian, and in keeping with Pal’s dedication towards educating a Western audiences in the ways of his country, it begins with a group of Western tourists in present-day India encountering an old man who then proceeds to tell them the story of the Buddha. The Light of Asia enjoyed modest success in Europe though it failed to find gain any bookings in Britain until Pal and Rai finally gained some attention for the film with a screening given before the royal family at Windsor Castle (King George V reportedly slept through it). The film also failed as an attraction in India.

Seeta Devi (Anglo-Indian actress Renée Smith) in A Throw of Dice

The film’s favourable reception in Europe led to two further productions, though owing to the lack of success in India the previous production finance source was no longer available to them. However, British companies were now showing interest, and British Instructional Films picked up the distribution rights for Shiraz (1928) and co-produced A Throw of Dice (1929) with UFA in Germany, both films therefore qualifying as Anglo-German productions. Both films were once again scripted by Pal and directed by Franz Osten, with Himansu Rai as lead performer among the all-Indian casts.

The Light of Asia, Shiraz and A Throw of Dice are each historical dramas set in India that stress exoticism (“halfway orientalist” is how Joyojeet Pal describes them), pandering as they do to a taste for a romantic India that was reflected in popular literature of the time. None is exceptional, but they are pleasing, well-constructed and attractively mounted productions which have found ready acceptance with audiences today, especially A Throw of Dice, which has enjoyed high profile through the score provided by Indian-British musician Nitin Sawhney, capped by a screening in London’s Trafalgar Square in 2007.

Pal perserved with British films for a while, writing further scenarios and seeing his story, His Honour the Judge, turned into the early talkie A Gentleman of Paris (1931), with Sinclair Hill directing and Sidney Gilliat the scriptwriter. It has no discernible Indian theme. Pal then returned to India, tried and failed to set up a film, Khyber Pass, to be filmed in Raycol colour and starring Clive Brook; had mixed fortunes making some films in India for his own Niranjan Pal Productions; then renewed his involvement with Himansu Rai and Franz Osten to become chief scenarist for the renowned Bombay Talkies. He stayed there until 1937, when he fell out with his fellow filmmakers (something of a recurring trait in Pal’s career, it has to be said), and concluded his career in film as a producer of advertising, documentary and newsreel films (he founded Aurora Screen News, 1938-42). He was also a pioneer of children’s films in India (with Hatey Khori, made in 1939).

Trailer for the documentary Niranjan Pal – A Forgotten Legend

Pal had been larely forgotten by the film industry and film historians when he died in 1959, but his son Colin went on to be an actor, technician and publicist for Hindi films (Pal had an English wife, née Lily Bell); his grandson Deep Pal is a cameraman; and his great grandson Joyojeet Pal is Assistant Professor of Information at the University of Michigan. He wrote his memoirs, entitled Such is Life, towards the end of his life, but they did not find a publisher, in Kolkata, until 1997.

Last year a project was launched by the South Asian Cinema Foundation in London to research Pal’s legacy, Lifting the Curtain: Niranjan Pal & Indo-British Collaboration in Cinema. With Heritage Lottery Fund support, the SACF has produced a documentary on Pal and published the memoirs for the first time in English, in a volume of essays, filmography and memoir, edited by Kusum Pant Joshi and Lalit Mohan Joshi, entitled Niranjan Pal: A Forgotten Legend & Such is Life: An Autobiography by Niranjan Pal. I was honoured to be asked to contribute a chapter, on Pal and the British film studios of the silent era. The evidence of Charles Urban, someone I have researched for many years, being so supportive on an impoverished and obscure Indian student when the rest of the film industry rebuffed him, was particularly heartening to learn. The volume’s wise introduction by Joyojeet Pal is particularly recommended.

Such is Life will have great value for anyone interested in the history of Indian nationalism or Anglo-British relations at the start of the twentieth century. It is also going to be of great interest to anyone interested in silent film history, from its eye-witness account of the Kinemacolor studios, to Pal’s sharp memory for the financial details of the deals won and lost when trying to get his films of the 1920s made. His memory is not always so sharp. Some dates are clearly wildly out – for example, he recalls being inspired to produce films from an Indian perspective after protesting outside a Lowell Thomas lecture-with-film on India. But Pal began his film career in 1912/13, five years before Thomas turned to the cinematograph, and ten years before Thomas made his travelogue Through Romantic India and into Forbidden Afghanistan, which was indeed the subject of Indian protests when presented at Covent Garden in London in 1922.

Niranjan Pal: A Forgotten Legend & Such is Life is available from the South Asian Cinema Foundation. A DVD is available of the accompanying 30mins documentary, though I don’t have details of how to obtain a copy except by contacting the SACF direct. Book and DVD were launched recently at the BFI Soutbank, and there is to be a launch event at the National Film Archive of India in Pune on 20 February 2012. A Throw of Dice, with the Nitin Sawhney scre, is available on DVD from the BFI in the UK and Kino in the USA. For those interested in Pal’s political background and that of the Indians in Britain around the time of India House and the burgeoning nationalist movement, I recommend the Open University’s Making Britain site, which has information on all the key individuals, locations, organisations and events. David Garnett’s autobiographical work, The Golden Echo (1953), recalls his friendship with Pal, known to him as Nanu, and other Indian nationalists in Britain (an extract is available here).

Niranjan Pal appears to have been hot-headed, a little gullible and tirelessly dedicated to his causes throughout his life. His life story was indeed his most dramatic production. It is certainly a story rich in incident and in the social, cultural and political themes of the times. That an Indian in the Britain of the 1910s and 20s should succeed in the way that he did, despite the racism that he clearly experienced on a continual basis, seems astonishing, though perhaps it was simply that he saw opportunities where others only saw hurdles. Hopefully the chance to read his life story will lead to further investigation of his life and times, and to DVD releases one day of The Light of Asia and Shiraz.