Ruggero Ruggeri as Hamlet in Amleto (1917)

It was the fervent belief of many in the early years of cinema that justification for the medium lay in how it interpeted stage drama. At a time when censorious authorities looked down upon the dubious cinema (with its low class audiences) and cinema was reaching out for respectability (and properties that were out of copyright), Pathé with its Film d’Art and Film d’Arte Italiana companies, and Adolph Zukor’s policy of ‘Famous Players in Famous Plays’ showed that there was financial good sense in bringing high-class drama to the cinema screen, however mutely.

The pinnacle of stage drama was, of course, William Shakespeare, and film companies in the silent film era took on the Bard with enthusiasm. The numbers are extraordinary. Some two hundred films, most of them one-reelers of the pre-war period, were produced that closely or loosely owed something to one or other of Shakespeare’s plays. Some film companies showed a particular interest: Vitagraph filmed Antony and Cleopatra, Julius Caesar, Macbeth, Othello, Richard III, Romeo and Juliet (all 1908), King Lear, A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1909), Twelfth Night (1910) and As You Like It (1912). Thanhouser made A Winter’s Tale (1910), The Tempest (1911), The Merchant of Venice (1912), Cymbeline (1913) and King Lear (1916). Cines, Kalem, Biograph, Ambrosio, Gaumont, Eclair, Nordisk, Milano and several others filmed the plays.

This was more than enthusiasm for high culture; it was good business. Shakespeare films appealed to an audience which found costume dramas in general to be a treat, and which was accustomed to boiled-down Bard from school texts and stage productions which concentrated on the highlights from the plays (such as the Crummles’ hectic production of Romeo and Juliet portrayed in Charles Dickens’ Nicholas Nickelby). Of course, not everyone wanted to see high culture quite as much as the cinema sometimes wanted to be associated with such culture (see the cartoon at the end of this post), but more than enough were impressed, and entranced.

Once films became longer – ironically as the cinema became closer in form to the theatre – the number of Shakespeare films fell, because longer productions were more of a challenge to audiences. But even then there was a burst of activity in 1916 (the tercentenary of Shakespeare’s death), with half-a-dozen or more productions in that year alone, and versions of the plays continued in silent form throughout the 1920s, with four key titles coming from Germany – Hamlet (1920, with Asta Nielsen as the Dane), Othello (1922, with Emil Jannings and Werner Krauss), Der Kaufman von Venedig (The Merchant of Venice) (1923, with Henny Porten) and Ein Sommernachtstraum (A Midsummer Night’s Dream) (1925, Werner Krauss again).

Prospero in his cave, from The Tempest (Clarendon 1908)

So where is the literature to back up this self-evidently significant corner of silent film history? Sadly, until recently, there has been very little. The silent film enthusiasts and film scholars have shied away from Shakespeare as being falsely worthy and far too uncinematic, while the Shakespeareans looked down on cinema per se, while finding the very notion of silent Shakespeare an absurdity. Jack J. Jorgens, a noted scholar, went so far as to write these dreadful words in his Shakespeare on Film (1977):

First came scores of silent Shakespeare films,one- and two-reelers struggling to render great poetic drama in dumb-show. Mercifully, most of them are lost.

Oh dear, oh dear. However, there was one work which almost eccentrically fought against the tide. Robert Hamilton Ball’s Shakespeare on Silent Film: A Strange Eventual History (1968) is one of the most remarkable books ever produced on silent cinema. It is a passionately-pursued archaeological investigation into every kind of Shakespeare film made during the silent era, encomapssing parodies, allusions, plot borrowing as well as ‘conventional’ adaptations, with Ball diggedly tracking down every obscure reference, every hidden print, every list of intertitles, with abundant fervour and an infectious interest in the people involved. This magnum opus has been cherished by the dedicated few for four decades, and for most of that time its discoveries and assertions have been taken as gospel. Yet even Ball ended his investigations with these disappointing words:

Silent Shakespeare film could not be art, a new art. The aesthetic problem is how to make good film which is good Shakespeare. It could not be good Shakespeare because too much was missing.

It is has been the task of a few of us (and I’ve been involved) to prove those words wrong. Silent Shakespeare was good Shakespeare, not because of what was missing, but because of what was there to be seen – a new medium expressing itself imaginatively while asserting its social worthiness and cultural relevance. To study silent Shakespeare films is to see films discovering what they could do. Yes there are histrionics at times, and yes there is some aburdity involved when complex plots are crammed into a ten-minute reel, but equally there is artistry, feeling and subtlety of interpretation. Have you ever seen a ballet of Romeo and Juliet and complained that the words were missing? Of course not. Shakespeare without the words is not a lesser form, but simply a form that requires its own special understanding. It expresses the significance of its subject within its specific constraints – which is precisely what art is.

The tide started to turn with the release of the British Film Institute’s video compilation Silent Shakespeare (1999), a work that was a revelation to many. Even hardened theatricals could see the special virtues in the Clarendon Film Company’s delightful reworking of The Tempest (1908) or the elemental passion evident in Ermete Novelli’s stunning performance in Re Lear (1910). The DVD has found its way onto many a university library shelf, while a number of scholars have begun to take on the silent Shakespeare film with fresh eyes – among them Jon Burrows, Roberta Pearson, Anthony Guneratne and Kenneth Rothwell.

The leading champion, however, has been Judith Buchanan, whose quite marvellous Shakespeare on Silent Film: An Excellent Dumb Discourse is published this month by Cambridge University Press. This is the sympathetic, understanding account of a phenomenon that we have been waiting for. It is not a comprehensive history of the silent Shakespeare film – Buchanan defers to Ball in that respect – instead it concentrates on exemplary films and on uncovering the social, cultural and economic contexts. So it is that an opening chapter details a nineteenth-century legacy of performance, with particular attention to Shakespeare and the magic lantern, showing that the silent Shakespeare film was part of an established tradition. Chapters then follow on the first Shakespeare film, King John (1899), featuring Herbert Beerbohm Tree (also on the BFI DVD); Shakespeare films of the ‘transitional era’ between the early and late 1900s, with close, engrossing readings of Clarendon’s The Tempest and Film d’Arte Italiana’s Othello (1909); the ‘corporate authorship’ of Vitagraph’s productions; the contrasting interpretations of Hamlet by Hepworth (a renowned British 1913 production with theatrical great Sir Johnston Forbes Robertson) and Amleto, a 1917 Italian film starring Ruggero Ruggeri, little-known but perhaps the most accomplished extant realisation on Shakespeare on silent film (it’s crying out for the two Hamlets to be released jointly on DVD); the several films of the tercentary year, including the rival Romeo and Juliets starring Francis X. Bushman/Beverley Bayne and Theda Bara/Harry Hilliard, both films alas lost; the German productions of the 1920s; and wordless Shakespeare today (there are some stage productions experimenting with silence, notably Paata Tsikurishvili’s Synetic Theatre).

It’s written for a literary studies audience, but it is grounded in exemplary original research (Buchanan has toured the world to track down the relevant prints) and it is a pleasure to read. There is much here to detain anyone keen to extend their knowledge of film history. She knows her films as well as her plays – a rare and most welcome combination. Above all, Buchanan opens up the subject in all its richness of theme, inviting others to explore further, illuminating the films that we are so fortunate have survived. We will still turn to Robert Hamilton Ball for his extensive documentary evidence, but to Buchanan for her sophisticated understanding.

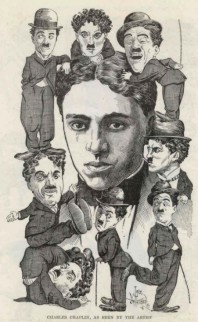

A 1913 cartoon from London Opinion, speaking for anyone resistant to the cinema’s occasional urge to impress Shakespeare upon us. Taken from Stephen Bottomore, I Want to See this Annie Mattygraph: A Cartoon History of the Coming of the Movies

If you are keen to seek out silent Shakespeare films for yourself (and you should, you really should) this is what’s currently available on DVD:

- Silent Shakespeare: includes King John (Biograph 1899), The Tempest (Clarendon 1908), A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Vitagraph 1909), Re Lear (Film d’Arte Italiana 1910), Twelfth Night (Vitagraph 1910), Il Mercante di Venezia (Film d’Arte Italiana 1910), Richard III (Co-operative 1911) [BFI] [Milestone]

- Thanhouser Presents Shakespeare [Thanhouser series vol.7]: includes The Winter’s Tale (1910), Cymbeline (1913), King Lear (1916) [Thanhouser]

- Richard III (Shakespeare Film Company 1912) [Kino]

- Othello (Wörner-Filmgesellschaft 1922): also includes Duel Scene from Macbeth (Biograph 1905), The Taming of the Shrew (Biograph 1908), Roméo se fait bandit (Pathé 1910), Desdemona (Nordisk 1911) [Kino]

The International Database of Shakespeare on Film, Radio and Television, an online filmographic database not yet officially released but available in a test version, hopes to be comprehensive for the silent Shakespeare film. Buchanan herself provides a filmography (restricted to films mentioned in her text), including the location of archive prints. Around forty silent Shakespeare films survive today, mercifully.