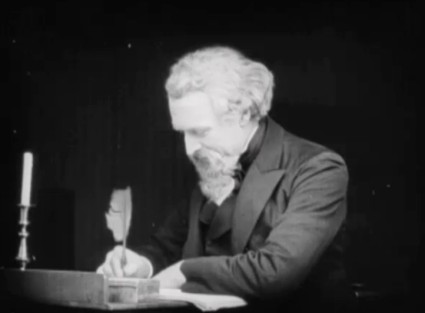

Charles Dickens portrayed in Dickens’ London (UK 1924)

Let Dickens and the whole ancestral array, going back as far as the Greeks and Shakespeare, be superfluous reminders that both Griffith and our cinema prove our origins to be not solely as of Edison and his fellow inventors, but as based on an enormous cultured past; each part of this past in its own moment of world history has moved forward the great art of cinematography.

Sergei Eisenstein

As I write this, in Rochester, Kent, I can look out of my window at the corner of St Margaret Street where, ninety-nine years ago, John Bunny drove past in a carriage, dressed as Mr Pickwick for the turning camera handles of the Vitagraph Company of America. And yesterday and today, on BBC television, we saw a fevered The Mystery of Edwin Drood, much of it filmed fifty yards away in the grounds and centre of Rochester cathedral. Here is the heart of Dickens, and the heart of a grand cinematographic tradition.

Charles Dickens was born two hundred years ago, and his great legacy is being celebrated with books, exhibitions, festivals, conferences, programmes and film seasons. His superabundant influence on cinema and television has been recognised in particular, with a three-month film season at the BFI Southbank underway, an Arena documentary Dickens on Film (with copious examples from the silent cinema) and new television productions of Drood and Great Expectations. Dickens remains something to see.

Dickens was hugely important to the silent cinema, as Eisenstein noted in his famous essay, ‘Dickens, Griffith and the Film Today’, which points out the principle of montage inherent in both Dickens’ novels and D.W. Griffith’s films. Every one of his novels was filmed during the silent era, most more than once. There were specialist Dickens filmmakers, such as Thomas Bentley and A.W. Sandberg. Charlie Chaplin (perhaps the most Dickensian of all filmmakers) loved his works, reading Oliver Twist many times over. It was not just Dickens the novelist who inspired the first filmmakers but Dickens the lover of theatre and the many stage dramatisations of his work. Dickens’s work naturally spilled out of the pages that could not fully contain them onto other dramatic platforms – the stage, the recital, the magic lantern, the cinema. Like all good works of the imagination, they transcend the boundaries of any one medium.

As a contribution to the Dickens bicentenary, and by way of demonstrating his great importance to early film, we have put together a filmography for Dickens and silent cinema. It may be the most extensive yet published; it certainly tries to clear up some of the confusion to be found in listings elsewhere, though there are still problematic corners, and doubtless films still to be identified. It lists both fiction (arranged under the works that inspired them) and non-fiction films, and notes where films still exist (as far as I can discover), and if they are available online or DVD. Where it says afilm is lost, this should not be taken as definitive, as some films will be held privately (noted here as Extant where I have information on these). Please let me know of any errors or omissions.

Barnaby Rudge

- Dolly Varden (UK 1906) d. Alf Collins p.c. Gaumont

Cast: not known

Length: 740ft Archive: Lost

Note: It is not entirely certain this is based on anything more than the name from Dickens’ novel (Gifford does not list it in his Books and Plays in Films 1896-1915) - Dolly Varden (USA 1913) d. Charles Brabin p.c. Edison

Cast: Mabel Trunnelle, Willis Secord, Robert Brower

Length: 1000ft Archive: Lost - Barnaby Rudge (UK 1915) d. Thomas Bentley p.c. Hepworth

Cast: Tom Powers (Barnaby Rudge), Violet Hopson (Emma Haredale), Stewart Rome (Maypole Hugh), Chrissie White (Dolly Varden)

Length: 5325ft Archive: Lost

Bleak House

- The Death of Poor Joe (UK 1901) d. G.A. Smith p.c. Warwick Trading Company

Cast: Laura Bayley (Joe), Tom Green (?) (nightwatchman)

Length: 50ft Archive: BFI

Note: Apparently based on the character of Jo the Crossing Sweeper [see comments for news of the discovery of this film] - Jo, the Crossing Sweeper (UK 1910) d. not known p.c. Walturdaw

Cast: not known

Length: 450ft Archive: Lost - Jo, the Crossing Sweeper (UK 1918) d. Alexander Butler p.c. Barker

Cast: Unity More (Jo), Dora de Winton (Lady Dedlock), Andre Beaulieu (Tulkinghorne)

Length: 5000ft Archive: Lost - Bleak House (UK 1920) d. Maurice Elvey p.c. Ideal

Cast: Constance Collier (Lady Dedlock), Berta Gellardi (Esther Summerson), E. Vivian Reynolds (Tulkinghorne)

Length: 6400ft Archive: BFI - Bleak House (Tense Moments from Great Plays) (UK 1922) d. Harry B. Parkinson p.c. Master

Cast: Sybil Thorndike (Lady Dedlock), Betty Doyle (Esther)

Length: 3100ft Archive: Extant (see comments)

The Chimes

- The Chimes (UK 1914) d. Thomas Bentley p.c. Hepworth

Cast: Stewart Rome (Richard), Violet Hopson (Meg Veck), Warwick Buckland (Trotty Veck)

Length: 2500ft Archive: Lost - The Chimes (USA 1914) d. Herbert Blaché p.c. US Amusement Corps

Cast: Tom Terriss (Trotty Veck), Faye Cusick (Meg)

Length: 5 reels Archive: Lost

Scrooge, or Marley’s Ghost (1901), the earliest surviving Dickens film

A Christmas Carol

- Scrooge; or, Marley’s Ghost (UK 1901) d. Walter R. Booth p.c. Paul’s Animatograph Works

Cast: Unknown

Length: 620ft Archive: BFI Availability: Dickens Before Sound DVD - A Christmas Carol (USA 1908) d. not known p.c. Essanay

Cast: Thomas Ricketts (Scrooge)

Length: 1000ft Archive: Lost - Il sogno dell’usuraio (Italy 1910) d. not known p.c. Cines

Cast: not known

Length: 675ft Archive: Lost

Note: English release title The Dream of Old Scrooge - A Christmas Carol (USA 1910) d. J. Searle Dawley (?) p.c. Edison

Cast: Marc McDermott (Scrooge), Charles Ogle (Bob Cratchit) Viola Dana

Length: 1000ft Archive: BFI, George Eastman House Availability: A Christmas Past DVD, Internet Archive - The Virtue of Rags (USA 1912) d. Theodore Wharton p.c. Essanay

Cast: Francis X. Bushman, Helen Dunbar, Bryant Washburn

Length: 1000ft Archive: Lost

Note: Very loose adaptation of Dickens’ story - Scrooge (UK 1913) d. Leedham Bantock p.c. Zenith

Cast: Seymour Hicks (Scrooge)

Length: 2500ft Archive: BFI - A Christmas Carol (UK 1914) d. Harold Shaw p.c. London

Cast: Charles Rock (Scrooge), Edna Flugrath (Belle), George Bellamy (Bob Cratchit), Mary Brough (Mrs Cratchit)

Length: 1340ft Archive: BFI - The Right to be Happy (aka Scrooge the Skinflint) (USA 1916) d. Rupert Julian p.c. Bluebird

Cat: Rupert Julian (Scrooge), John Cook (Bob Cratchit), Claire McDowell (Mrs Cratchit)

Length: 5 reels Archive: Lost - My Little Boy (USA 1917) d. Elsie Jane Wilson p.c. Bluebird

Cast: Winter Hall (Uncle Oliver), Zoe Rae (Paul), Ella Hall (Clara), Emory Johnson (Fred)

Length: 5 reels Archive: Lost

Note: Based on A Christmas Carol and the nursery rhyme ‘Little Boy Blue’ - Scrooge (Tense Moments with Great Authors) (UK 1922) d. George Wynn p.c. Master

Cast: H.V. Esmond (Scrooge)

Length: 1280ft Archive: Extant (see comments) - Scrooge (Gems of Literature) (UK 1923) d. Edwin Greenwood p.c. British & Colonial

Cast: Russell Thorndike (Scrooge), Jack Denton (Bob Cratchit)

Length: 1600ft Archive: Lost

The Cricket on the Hearth

- The Cricket on the Hearth (USA 1909) d. D.W. Griffith p.c. Biograph

Cast: Owen Moore (Edward Plummer), Violet Mersereau (May Fielding), Linda Arvidson (Sister Dorothy)

Length: 985ft Archive: MOMA, George Eastman House, Library of Congres Availability: Dickens Before Sound DVD - The Cricket on the Hearth (USA 1914) d. Lorimer Johnston p.c. American

Cast: Sydney Ayres, Vivian Rich

Length: 2000ft Archive: Lost - The Cricket on the Hearth (USA 1914) d. Lawrence Marston p.c. Biograph

Cast: Jack Drumeir, Alan Hale

Length: 2 reels Archive: George Eastman House, MOMA Available: Grapevine Video DVD-R - Sverchok na Pechi (Russia 1915) d. Boris Sushkevich and A. Uralsky p.c. Russian Golden Series

Cast: Grigori Khmara, Yevgeni Vakhtangov

Length: 710m Archive: Lost - Le grillon du foyer (France 1922) d. Jean Manoussi p.c. Eclipse

Cast: Charles Boyer, Marchel Vibart, Sabine Landray

Length: ? Archive: Lost? - The Cricket on the Hearth (USA 1923) d. Lorimer Johnston p.c. Paul Gerson

Cast: Josef Swickard (Caleb Plummer), Fritzi Ridgeway (Bertha Plummer), Paul Gerson (John Perrybingle)

Length: 7 reels Archive: UCLA (1 reel only) [see also comments]

David Copperfield

- Love and the Law (USA 1910) d. Edwin S. Porter p.c. Edison

Cast: Edwin August, Charles J. Brabin

Length: 1000ft Archive: Lost - David Copperfield: part 1; The Early Life of David Copperfield (USA 1911) d. Theodore Marston p.c. Thanhouser

Cast: Flora Foster (David as a boy), Anna Seer (David’s mother), Marie Eline (Emily as a girl), Frank Crane

Length: 950ft Archive: Museo Nazionale del Cinema (incomplete?) - David Copperfield: part 2; Little Emily and David Copperfield (USA 1911) d. Theodore Marston p.c. Thanhouser

Cast: Ed Genung (David), Florence La Badie (Emily)

Length: 950ft Archive: Museo Nazionale del Cinema (incomplete?) - David Copperfield: part 3; The Loves of David Copperfield (USA 1911) d. Theodore Marston p.c. Thanhouser

Cast: d. Ed Genung (David)

Length: 1000ft Archive: Museo Nazionale del Cinema (incomplete?) - Little Emily (UK 1911) d. Frank Powell p.c. Britannia

Cast: Florence Barker (Emily)

Length: 1254ft Archive: Lost - David Copperfield (UK 1913) d. Thomas Bentley p.c. Hepworth

Cast: Kenneth Ware (David Copperfield), Eric Desmond (David as a child), Len Bethel (David as a youth), Alma Taylor (Dora), H. Collins (Micawber), Jack Hulcup (Uriah Heep)

Length: 7500ft Archive: BFI Availability: Dickens Before Sound DVD, 8mins extract - David Copperfield (Denmark 1922) d. A.W. Sandberg p.c. Nordisk

Cast: Gorm Schmidt (David as a adult), Martin Herzberg (David as a boy), Karen Winther (Agnes as a woman), Else Neilsen (Agnes as a girl), Frederik Jensen (Micawber), Karina Bell (Dora), Margarete Schlegel (David’s mother), Rasmus Christiansen (Uriah Heep)

Length: 3095m Archive: Danish Film Institute Availability: Clips on www.dfi.dk

Dombey and Son

- Dombey and Son (UK 1917) d. Maurice Elvey p.c. Ideal

Cast: Norman McKinnel (Paul Dombey), Lilian Braithwaite (Edith Dombey), Hayford Hobbes (Walter Dombey)

Length: 6800ft Archive: George Eastman House

Store Forventninger (Denmark 1922) directed by A.W. Sandberg, from http://www.dfi.dk

Great Expectations

- The Boy and the Convict (UK 1909) d. Dave Aylott p.c. Williamson

Cast: Unknown

Length: 750ft Archive: BFI Availability: Dickens Before Sound DVD - Great Expectations (USA 1917) d. Robert D. Vignola p.c. Famous Players

Cast: Jack Pickford (Pip), Louise Huff (Estella), Frank Losee (Magwitch), W.W. Black (Joe Gargery), Grace Barton (Miss Havisham)

Length: 5 reels Archive: Lost - Store Forventninger (Denmark 1922) d. A.W. Sandberg p.c. Nordisk

Cast: Martin Herzberg (young Pip), Harry Komdrup (adult Pip), Marie Dinesn (Miss Havisham), Emil Helsengreen (Magwitch)

Length: 2527m Achive: Danish Film Institute Availability: Clips on www.dfi.dk

Hard Times

- Hard Times (UK 1915) d. Thomas Bentley p.c. Transatlantic

Cast: Bransby Williams (Gradgrind), Leon M. Lion (Tom Gradgrind), Dorothy Bellew (Louisa), Madge Tree (Rachael)

Length: 4000ft Archive: Lost

Little Dorrit

- Little Dorrit (USA 1913) d. James Kirkwood p.c. Thanhouser

Cast: Maude Fealy, Alphonse Ethier, Harry Benham

Length: 3 reels Archive: Lost - Klein Djoorte (Germany 1917) d. Frederic Zelnik p.c. Berliner

Cast: Lisa Weisse (Djoorte), Karl Beckersachs (Geert), Aenderli Lebius (Batarama)

Length: 4 reels Archive: Lost - Little Dorrit (UK 1920) d. Sidney Morgan p.c. Progress

Cast: Joan Morgan (Amy Dorrit), Lady Tree (Mrs Clenman), Langhorne Burton (Arthur Clenman)

Length: 6858ft Archive: Screen Archive South East (20mins only) Availability: SASE website - Lille Dorrit (Denmark 1924) d. A.W. Sandberg p.c. Nordisk

Cast: Karina Bell (Amy Dorrit), Frederik Jensen (William Dorrit), Gunnar Tolnæs (Arthur Clennam)

Length: 3245m Archive: BFI

Martin Chuzzlewit

- Martin Chuzzlewit (USA 1912) d. Oscar Apfel and J. Searle Dawley p.c. Edison

Cast: Guy Hedlund, Harold Shaw, Marion Brooks

Length: 3 reels Archive: Lost - Martin Chuzzlewit (USA 1914) d. Travers Vale p.c. Biograph

Cast: Alan Hale, Jack Drumeir

Length: 2 reels Archive: George Eastman House

Mrs Lirriper’s Legacy

- Mrs Lirriper’s Legacy (USA 1912). d. not known (Van Dyke Brooke?) p.c. Vitagraph

Cast: Mary Maurice (Mrs Lirriper)

Length: 1000ft Archive: Lost

Mrs Lirriper’s Lodgers

- Mrs Lirriper’s Lodgers (USA 1912) d. Van Dyke Brooke p.c. Vitagraph

Cast: Mary Maurice (Mrs Lirriper), Clara Kimball Young (Mrs Edson), Courtney Foote (Mr Edison), Van Dyke Brooke (Jackman)

Length: 1000ft Archive: Lost

The Mystery of Edwin Drood

- The Mystery of Edwin Drood (UK 1909) d. Arthur Gilbert p.c. Gaumont

Cast: Cooper Willis (Edwin Drood), Nancy Bevington (Rosa Bud)

Length: 1030ft Archive: Lost - [The Mystery of Edwin Drood] (France 1912) d. not known p.c. Film d’Art

Cast: not known

Length: 1970ft Archive: Lost

Note: As a Film d’Art production this would have been made by Pathé, but I have not traced a record of it or an original title in the Pathé catalogue - The Mystery of Edwin Drood (USA 1914) d. Herbert Blaché and Tom Terriss p.c. World

Cast: Tom Terriss (John Jasper), Vinnie Burns (Rosa Bud), Rodney Hickock (Edwin Drood)

Length: 5 reels Archive: Lost

Thanhouser’s 1912 Nicholas Nickelby, with Harry Benham as Nicholas

Nicholas Nickleby

- Dotheboys Hall; or, Nicholas Nickleby (UK 1903) d. Alf Collins p.c. Gaumont

Cast: William Carrington (pupil [Smike?])

Length: 225ft Archive: BFI - A Yorkshire School (USA 1910) d. James H. White p.c. Edison

Cast: Verner Clarges

Length: 800ft Archive: Lost - Nicholas Nickleby (USA 1912) d. George Nicholls p.c. Thanhouser

Cast: Harry Benham (Nicholas Nickelby), Mignon Anderson (Madeline Bray), Frances Gibson (Kate Nickelby), David H. Thompson (Squeers), Justus D. Barnes (Ralph Nickleby)

Length: 2 reels Archive: BFI Availability: Dickens Before Sound DVD, Thanhouser Vimeo channel

The Old Curiosity Shop

- Little Nell (UK 1906 d. Arthur Gilbert p.c. Gaumont

Cast: Thomas Nye

Length: ? Archive: Lost

Note: Chronophone film designed to be synchronised with disc recording - The Old Curiosity Shop (USA 1909) d. not known p.c. Essanay

Cast: Marcia Moore (Little Nell)

Length: 1000ft Archive: Lost - The Old Curiosity Shop (USA 1911) d. Barry O’Neill p.c. Thanhouser

Cast: Marie Eline (Little Nell), Frank Hall Crane (Grandfather), Marguerite Snow, Harry Benham

Length: ? Archive: BFI - The Old Curiosity Shop (UK 1912) d. Frank Powell p.c. Britannia

Cast: Not known

Length: 990ft Archive: Lost - The Old Curiosity Shop (UK 1913) d. Thomas Bentley p.c. Hepworth

Cast: Mai Deacon (Little Nell), E. Fleton (Quilp), Alma Taylor (Mrs Quilp), Willie West (Dick Swiveller), Warwick Buckland (Grandfather Trent)

Length: 5300ft Archive: Lost - The Old Curiosity Shop (UK 1921) d. Thomas Bentley p.c. Welsh-Pearson

Cast: Mabel Poulton (Little Nell), William Lug (Grandfather), Pino Conti (Quilp)

Length: 6587ft Archive: Lost - La bottega dell’antiquario (Italy 1921) d. Mario Corsi p.c. G. Salvini

Cast: Gustavo Salvini, Robert Sortsch-Pla, Egle Valery

Length: 1987m Archive: Lost

Oliver Twist

- The Death of Nancy Sykes (USA 1897) d. not known p.c. American Mutoscope

Cast: Mabel Fenton (Nancy), Charles Ross (Bill Sykes)

Length: Archive: Lost - Mr Bumble’s Courtship (aka Mr Bumble the Beadle) (UK 1898) d. not known p.c. Paul’s Animatograph Works

Cast: not known

Length: 60 ft Archive: Lost - Oliver Twist (France 1905) d. not known p.c. Gaumont

Cast: not known

Length: 750ft Archive: Lost

Note: Pointer gives 1906 date, Gifford says 1905 - A Modern Day Fagin (UK 1905) d. not known p.c. Walturdaw

Cast: not known

Length: 250ft Archive: Lost - The Modern Oliver Twist; or The Life of a Pickpocket (USA 1906) d. not known p.c. Vitagraph

Cast: not known

Length: 475ft Archive: Lost - Oliver Twist (USA 1909) d. J. Stuart Blackton p.c. Vitagraph

Cast: Edith Storey (Oliver Twist), Elita Proctor Otis (Nancy), William Humphrey (Fagin)

Length: 995ft Archive: BFI - L’enfance d’Oliver Twist (France 1910) d. Camille de Morlhon p.c. Film d’Art

Cast: Renée Pré (Oliver Twist), Jean Périer (Fagin), Marie Dornay (Rose)Length: 295m Archive: Lost - Storia di un orfano (Italy 1911) d. not known p.c. Cines

Cast: not known

Length: 1424ft Archive: Lost - Oliver Twist (USA 1912) d. not known p.c. General Film Publicity

Cast: Nat C. Goodwin (Fagin), Vinnie Burns (Oliver Twist), Mortimer Martine (Bill Sykes), Beatrice Moreland (Nancy), Charles Rogers (Artful Dodger)

Length: 5 reels Archive: Incomplete print exists (according to Silent Era) - Brutality (USA 1912) d. D.W. Griffith p.c. Biograph

Cast: Walter Miller (young man), Mae Marsh (young woman), Joseph Graybill (victim of anger)

Length: 2 reels Archive: Library of Congress, MOMA

Note: Plot features an abusive husband who sees the error of his ways after seeing Bill Sikes in stage production of Oliver Twist - Oliver Twist (UK 1912) d. Thomas Bentley p.c. Hepworth

Cast: Ivy Millais (Oliver), John McMahon (Fagin), Harry Royston (Bill Sykes), Alma Taylor (Nancy), Willie West (Artful Dodger)

Length: 3700ft Archive: Lost?

Note: Clips from this film, all that may survive, are included in the travelogue Dickens’ London (UK 1924), held by the BFI - The Queen of May (USA 1912) d. not known p.c. Republic Film Company

Cast: not known

Length: c.800ft Archive: BFI

Note: Drama about a poor mother and her daughter, who performs in a stage production of Oliver Twist. - A Female Fagin (USA 1913) d. not known p.c. Kalem

Cast: not known

Length: 910ft Archive: BFI

Note: Probably only marginal relationship to Oliver Twist - Oliver Twist Sadly Twisted (USA 1915) d. not known p.c. Superba

Cast: not known

Length: ? Archive: Lost

Note: Presumably a parody of some sort - Oliver Twist (USA 1916) d. James Young p.c. Lasky

Cast: Marie Doro (Oliver), Hobart Bosworth (Bill Sykes), Tully Marshall (Fagin), Elsie Jane Wilson (Nancy), Raymond Hatton Artful Doger), W.S. Van Dyke (Charles Dickens)

Length: 5 reels p.c. Lost - Oliver Twisted (UK 1917) d. Fred Evans, Joe Evans p.c. Piccadilly

Cast: Fred Evans (Pimple)

Length: 2360ft Archive: Lost

Note: Probably parodying USA 1916 Oliver Twist - Twist Olivér (Hungary 1919) d. Márton Garas p.c. Corvin

Cast: Tibor Luinszky (Oliver), Sári Almási (Nancy), Gyula Szöreghy (Sikes), László Z. Molnár (Fagin)

Length: 6 reels Archive: Jugoslovenska Kinoteka (incomplete, 4 reels) - Die Geheimnisse von London – Die Tragödie eines Kindes (Germany 1920) d. Richard Oswald p.c. Leyka/Richard Oswald

Cast: Manci Lubinsky (Percy), Louis Ralph (Jim), Adolph Weisse (Fagin)

Length: 2137m Archive: Lost? - Oliver Twist Jr. (USA 1921) d. Millard Webb p.c. Fox

Cast: Harold Goodwin (Oliver Twist Jr), Clarence Wilson (Fagin), G. Raymond Nye (Bill Sikes), Scott McKee (Artful Dodger), Irene Hunt (Nancy)

Length: 5 reels p.c. Lost - Nancy (Tense Moments with Great Authors) (UK 1922) d. Harry B. Parkinson p.c. Master

Cast: Sybil Thorndike (Nancy), Ivan Berlyn (Fagin)

Length: 1578ft Archive: Lost - Fagin (Tense Moments with Great Authors) (UK 1922) d. Harry B. Parkinson p.c. Master

Cast: Ivan Berlyn (Fagin)

Length: 1260ft Archive: Lost - Oliver Twist (USA 1922) d. Frank Lloyd p.c. Jackie Coogan

Cast: Jackie Coogan (Oliver), Lon Chaney (Fagin), George Sigmann (Bill Sikes), Gladys Brockwell (Nancy), Joan Standing (Charlotte), Edouard Trebaol (Artful Dodger)

Length: 7761ft Archive: Film Preservation Associates, LoC, UCLA Available: Dickens Before Sound DVD, Image Entertainment DVD

Our Mutual Friend

- How Bella Was Won (USA 1911) d. not known p.c. Edison

Cast: George Soule Spencer

Length: ? Archive: Lost - Eugene Wrayburn (USA 1911) d. not known p.c. Edison

Cast: Darwin Karr, Richard Ridgeley, Bliss Milford

Length: 1000ft Archive: Lost

Note: A third Edison adaptation from Our Mutual Friend, entitled Bella Wilder’s Return is listed by www.dickensandshowbiz.com but the film was never made - Vor fælles Ven (Denmark 1921) d. A.W. Sandberg p.c. Nordisk

Cast: Peter Fjelstrup (Hexam), Karen Caspersen (Lizzie), Peter Malberg (Eugene Wayburn)

Length: 4664m Archive: Lost

The Pickwick Papers

- Mr Pickwick’s Christmas at Wardle’s (UK 1901) d. Walter R. Booth p.c. Paul

Cast: not known

Length: 140ft Archive: Lost - Gabriel Grub, the Surly Sexton (UK 1904) d. James Williamson p.c. Williamson

Cast: not known

Length: 400ft Archive: Lost - A Knight for a Night (USA 1909) d. not known p.c. Edison

Cast: not known

Length: 370ft Archive: Lost - Mr Pickwick’s Predicament (USA 1912) d. J. Searle Dawley p.c. Edison

Cast: Charles Ogle, Mary Fuller, Marc McDermott

Length: 1000ft Archive: Extant - Pickwick Papers: episode 1; The Honourable Event (USA 1913) d. Larry Trimble p.c. Vitagraph

Cast: John Bunny (Pickwick), James Piror (Mr Tupman), H.P. Owen (Sam Weller)

Length: 1 reel Archive: BFI Availability: Dickens Before Sound DVD - Pickwick Papers: episode 2; The Adventure of Westgate Seminary (USA 1913) d. Larry Trimble p.c. Vitagraph

Cast: John Bunny (Pickwick), James Prior (Mr Tupman), H.P. Owen (Sam Weller)

Length: 1 reel Archive: BFI - Pickwick Papers: episode 3; The Adventure of the Shooting Party (USA 1913) d. Larry Trimble p.c. Vitagraph

Cast: John Bunny (Pickwick), Fred Hornby (Winkle), H.P. Owen (Sam Weller)

Length: 1 reel Archive: Lost?

Note: The first two episodes (which were also shown together as a two-reeler) were released February 1913, and the third episode in September 1913. - Pickwick versus Bardell (Clarendon Speaking Pictures) (UK 1913) d. Wilfred Noy p.c. Clarendon

Cast: not known

Length: 1000ft Archive: Lost

Note: Dramatisation to accompany stage recital - Mr Pickwick in a Double-Bedded Room (UK 1913) d. Wilfred Noy p.c. Clarendon

Cast: not known

Length: 1000ft Archive: Lost

Note: Dramatisation to accompany stage recital - Mrs Corney Makes the Tea (UK 1913) d. Wilfred Noy p.c. Clarendon

Cast: not known

Length: 1000ft Archive: Lost

Note: Dramatisation to accompany stage recital - The Adventures of Mr Pickwick (UK 1921) d. Thomas Bentley p.c. Ideal

Cast: Fred Volpe (Pickwick), Mary Brough (Mrs Bardell), Ernest Thesiger (Mr Jingle), Hubert Woodward (Sam Weller), Bransby Williams (Sgt Buzfuz)

Length: 6000ft Archive: Lost

Sketches by Boz

- Mr Horatio Sparkins (USA 1913) d. not known p.c. Vitagraph

Cast: Courtenay Foote (Horatio Sparkins), Flora Finch (Teresa Halderton)

Length: 1000ft Archive: Lost

A Tale of Two Cities

- A Tale of Two Cities (USA 1908) d. not known p.c. Selig

Cast: not known

Length: 1000ft Archive: Lost - A Tale of Two Cities (USA 1911) d. William Humphrey p.c. Vitagraph

Cast: Maurice Costello (Sidney Carton), Norma Talmadge (Lucy Manette)

Length: 3021ft Archive: BFI, MOMA, UCLA Availability: Grapevine Video DVD-R - A Tale of Two Cities (USA 1917) d. Frank Lloyd p.c. Fox

Cast: William Farnum (Charles Darney / Sydney Carton), Jewel Carmen (Lucie Manete), Charles Clary (Marquis St. Evremonde), Rosita Marstini (Madame De Farge)

Length: 7 reels Archive: UCLA - The Birth of a Soul (USA 1920) d. Edwin L. Hollywood p.c. Vitagraph

Cast: Harry T. Morey (Philip Grey/Charles Drayton), Jean Paige (Dorothy Barlow)

Length: 4986ft Archive: Lost

Note: Loose adaptation in American setting - A Tale of Two Cities (Tense Moments with Great Authors) (UK 1922) d. W.C. Rowden p.c. Master

Cast: J. Fisher White (Dr Manette), Clive Brook (Sidney Carton), Ann Trevor (Lucie Manette)

Length: 1174ft Archive: Lost - The Only Way (UK 1926) d. Herbert Wilcox p.c. Herbert Wilcox

Cast: John Martin Harvey (Sidney Carton), Madge Stuart (Mimi), Betty Faire (Lucie Manette), J. Fisher White (Dr Manette)

Length: 10075ft Archive: BFI

Other fiction

- Leaves from the Books of Charles Dickens (UK 1912) d. not known p.c. Britannia

Cast: Thomas Bentley (multiple roles)

Length: 740ft Archive: Cinémathèque Française, Gaumont Pathé Archives - Master and Pupil (USA 1912) d. J. Searle Dawley p.c. Edison

Cast: Harry Furniss (The Master), Mary Fuller (his daughter), Harold Shaw (pupil)

Length: 1000ft Archive: Lost

Note: Story about an impoverished artist who illustrates the works of Dickens - Dickens Up-to-Date (Syncopated Picture Plays) (UK 1923) d. Bertram Phillips p.c. Bertram Phillips

Cast: Queenie Thomas

Length: 1900ft Archive: Lost

Note: Comedy burlesque

Uncertain titles

Some sources give a Barnaby Rudge (USA 1911) directed by Charles Kent. Kent was working at this time for Vitagraph, and there is no record of such a Vitagraph production. Denis Gifford, in Books and Plays in Films 1896-1915, lists a one-reel Oliver Twist apparently made in Denmark in 1910, but no such production can be found in the online Danish filmography. Some sources list a German Oliver Twist directed by Lupu Pick in 1920, but this appears to have been a production announced but not completed. Magliozzi lists an American 1922 Scrooge held by UCLA, but this is probably the UK title from the Tense Moments with Great Authors series. The 1924 Bonzo cartoon Playing the Dickens in an Old Curiosity Shop (UK 1925) uses only Dickens’ title. The UK 1904 film Mr Pecksniff Fetches the Doctor has no connection with Martin Chuzzlewit.

The Pickwick Coach halts near to the future New Bioscope Towers, from the newsreel Mr Pickwick (Pathé Gazette) (1927), from British Pathe

Non-fiction

- In Dickens’ Land (France 1913) p.c. Pathé / Travelogue / Archive: Lost [original French title not traced]

- The Royal City of Canterbury (UK 1915) p.c. Gaumont / Travelogue / 610ft / Archive: BFI

- Americans Place Wreath on Dickens Tomb at Westminster Abbey (Gaumont Graphic 719) (UK 11-Feb-18) p.c. Gaumont / Newsreel / Archive: Lost?

- Dickens’ Birth Anniversary (Pathé Gazette) (UK 1918) p.c. Pathé / Newsreel / Archive: British Pathé Available: British Pathé

- Dickens’ Fair at Botanic Gardens for Home for Blinded Sailors and Soldiers (Gaumont Graphic 783) (UK 23-Feb-18) p.c. Gaumont / Newsreel / Archive: Lost?

- Homage to Dickens (Pathé Gazette) (UK 1919) p.c. Pathé / Newsreel / Archive: British Pathé Available: British Pathé

- Dicken’s [sic] Anniversary (Pathé Gazette 641) (UK 12-Feb-20) p.c. Pathé / Newsreel / Archive: British Pathé Available: British Pathé

- untitled (Around the Town no. 15) (UK 11-Mar-20) p.c. Around the Town / Cinemagazine / Archive: Lost

- Sir John Martin-Harvey Now Appearing in “The Only Way” (Around the Town no. 105) (UK 01-Dec-21) p.c. Around the Town / Cinemagazine / Archive: Lost

- Dickens Procession and Confetti Carnival – Southport (Gaumont Graphic 1184) (UK 27-Jul-22) p.c. Gaumont / Newsreel / Archive: Lost?

- The All-Lancashire Dickens (Pathé Gazette) (UK 1922) p.c. Pathé / Newsreel / Archive: British Pathé Available: British Pathé

- Dickens Pageant at Camden Town. Famous Author’s Boyhood Home the Scene of Costume Carnival (Gaumont Graphic 1212) (UK 02-Nov-22) p.c. Gaumont / Newsreel/ Archive: Lost?

- 113th Dickens’ Anniversary (Pathé Gazette 1163) (UK 12-Feb-22) p.c. Pathé / Newsreel / Archive: British Pathé Available: British Pathé

- Dickens’ London (Wonderful London) (UK 1924) p.c. Graham-Wilcox / Travelogue / Length: 780ft Archive: BFI Available: Dickens Before Sound DVD

- Within the Sound of Bow Bells (Wonderful London) (UK 1924) p.c. Graham-Wilcox / Travelogue / Length: 839ft / Archive: BFI

- No. 3 Char-a-banc Tour to Rochester (UK 1924) p.c. London General Omnibus Company / Travelogue / Length: 1066ft / Archive: BFI

- As in the Days of Dickens (Topical Budget 762-2) (UK 05-Apr-26) p.c. Topical / Newsreel / Archive: BFI

- Dickens Golden Wedding (Empire News Bulletin 43) (UK 27-Sep-26) p.c. British Pictorial Productions / Newsreel / Archive: Lost?

- The Golden Wedding of Sir Henry Fielding Dickens and Lady Dickens, 25th September 1926 (UK 1926) / Actuality / Archive: BFI

- Pickwick Club (Empire News Bulletin 109) (UK 16-May-27) p.c. British Pictorial Productions / Newsreel / Archive: Lost?

- Frilled Cravats and Flowered Waistcoats (Topical Budget 820-2) (UK 16-May-1927) p.c. Topical Film Company / Newsreel / Archive: BFI

- Mr Pickwick (Pathé Gazette) (UK 16-May-27) p.c. Pathé / Newsreel / Archive: British Pathé Available: British Pathé

- Ye Dickens Coach 1827-1927 (unreleased?) (UK 1927) p.c. Gaumont / Newsreel / Archive: ITN Source Available: ITN Source

- Literature’s Loss (Gaumont Graphic 1756) (UK 19-Jan-28) p.c. Gaumont / Newsreel / Archive: ITN Source Available: ITN Source

- To the Royal Hop Pole Hotel for Dinner! (Pathé Super Gazette) (UK 30-Jul-28) p.c. Pathé / Newsreel / Archive: British Pathé Available: British Pathé

- Mr Pickwick and Party (Topical Budget) (UK 30-Jul-28) p.c. Topical Film Company / Newsreel / Archive: BFI

- Pickwick Centenary at Tewkesbury (unreleased?) (UK 1928) p.c. Gaumont / Newsreel / Archive: ITN Source Available: ITN Source

- Lorry as a Stage: Dickensian Tabard Players Perform Outside the ‘Old Curiosity Shop’ (Empire News Bulletin) (UK 7-Feb 1929) p.c. British Pictorial Productions / Newsreel / Archive: BFI

- 1812-1970 – Is Wisions About? (Gaumont Graphic 1868) (UK 14-Feb-29) p.c. Gaumont / Newsreel / Archive: ITN Source Available: ITN Source

- The Old Curiosity Shop (Pathé Super Gazette) (UK 12-Jun-300 p.c. Pathé / Newsreel / Archive: British Pathé Available: British Pathé

This filmography is indebted to the American Film Index volumes, Denis Gifford’s British Film Catalogue and Books and Plays in Films 1896-1915, Ron Magliozzi’s Treasures from the Film Archives, the Silent Era website’s Progressive Silent Film List, Filmportal, the Danish national filmography, the American Film Institute Catalog for silent films, the Pordenone Silent Film Festival’s Vitagraph Company of America catalogue, the BFI Film & TV Database, News on Screen, the IMDb and other sources. Only when I had exhausted these did I turn to the filmography in Michael Pointer’s Charles Dickens on the Screen. This had two or three titles that had eluded me, a number of film lengths that I hadn’t tracked down, and all in all is a fine piece of research. I commend it to you.

Update (12 February 2012): My thanks to friends at the BFI for some corrections and additions now made to this filmography.