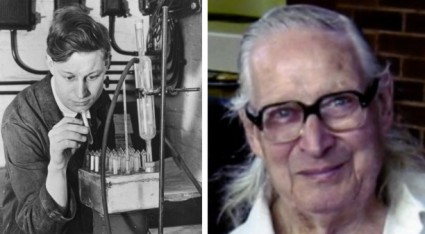

Harold Brown, on left in the 1940s (from the British Film Institute), on the right in 2008 (courtesy of Eve Watson)

You will not find the name of Harold Brown in many film history books, but there are quite a number of film histories that could not have been written without him. Harold, who died on Friday 14 November, essentially invented the art and science of film preservation. Countless films have been preserved either by his hands, or by the hands of those he tutored, or those archives around the world who adopted his methods.

It was in 1935 that Harold Brown (born 1919) started as office boy at the newly-formed British Film Institute, where Ernest Lindgren was setting up the National Film Library. Brown was subsequently to become its first preservation officer. In the early 1930s there were no film archives, or almost none. In that decade the four great national archives that were to become pillars of the film archiving movement were established: the Museum of Modern Art Film Library (New York), the Reichsfilmarchiv (Berlin) and the National Film Library (London) in 1935, the Cinémathèque Française (Paris) in 1936. These archives were established by a dedicated band of pioneer archivists with a passion for the film as art. They were driven in particular by the passing of the silent film era, and the imminent loss of the films of that first period of cinema history, films which were being dumped by the studios who saw no value in a heritage that they could no longer sell to anyone.

Harold Brown printing a film using the Mark IV

Ernest Lindgren, as Curator of the National Film Library (later the National Film Archive and now the BFI National Archive), laid down principles and Harold Brown came up with the working methods which formed the basis for film preservation. The original film was, as far as possible, inviolate. It needed to be copied, in a form as faithful to the original as possible. Films needed to be treated not only according to their importance but to the extent of, or their potential for, chemical decay. One of Harold’s most notable achievements was the artificial ageing test, which enabled archivists to determine when a film was likely to start deteriorating, and at what time it should be copied. This allowed archives to plan sensibly for the future. A noticeable legacy of Harold’s is the punch holes that you will see occasionally in National Film Archive prints, created so that a circle of film could be put through the ageing test. Another famous Brown creation was the Mark IV, a step printer for dealing with shrunken and non-standard perforation film, built out of bits of toy Meccano, string, rubber bands and parts from a 1905 Gaumont projector.

Harold was a self-taught pioneer. His investigations established basic methods for the identification of early film formats, the repair of damaged film, the storage of film, and the treatment of colour film (his work on Douglas Fairbanks’ 1926 film The Black Pirate, in two-colour Technicolor, was an early classic of film restoration). Awarded an MBE in 1967, he carried working at the National Film Archive until 1984, though he continued as a mentor and consultant to film archives internationally, well into retirement. He passed on his knowledge not only in person, but through some key publications. His Basic Film Handling (1985) and Physical Characteristics of Early Films as Aids to Identification (1990) are standard reference guide to the film archiving profession, and the latter is still available from the site of the Federation of International Film Archives (FIAF). Nor was he solely a nitrate era or early film specialist. He stayed abreast of issues in film archiving throughout, and it was he who gave the name ‘vinegar syndrome’ to the phenomenon of the degredation of acetate film which film archives discovered, to their alarm, in the 1980s.

You can see Harold at work in his prime in a 1963 Pathe Pictorial report on the work of the National Film Archive, available from the British Pathe site (just type in ‘film archive’, or click here for the same film from ITN Source). He features towards the end, delicately handling four frames of film, then seen operating the Mark IV. If you can, check out his modest four-page memoir in the FIAF publication This Film is Dangerous: A Celebration of Nitrate Film, edited by Roger Smither. Or you can read about how Brown and Lindgren went about creating a film archive in Penelope Houston’s Keepers of the Frames: The Film Archives (1994). Or read this text by David Francis (Lindgren’s successor as Curator of the National Film Archive) for this year’s Pordenone Silent Film Festival catalogue on Brown’s role overseeing the projection of the 548 films dating 1900-1906 shown at the seminal 1978 FIAF symposium on early film. Or get a copy of the BFI compilation DVD, Early Cinema: Primitives and Pioneers, most of the examples of which are films that Harold took in, preserved, and made available for future generations.

Harold was a wise, methodical, determined and kindly man. I was lucky enough to know him and to exchange information with him on early film formats at my time at the BFI, in the mid-1990s. I was rather awe-struck just to be holding conversations with him, but I found him to be every inch a gentleman. He has been held in reverence by generations of budding film archivists, and even as his pioneering methods have been superseded by more sophisticated technology, and as the film archiving profession now encounters the digital frontier, his understanding of the life – and the after-life – of a film underpins all that a film archive stands for. Gladly would he learn and gladly teach. Thank you, Harold.