Photographers and cinematographers at the 1924 Olympic Games in Paris, from the official report, available at http://www.la84foundation.org

Note: This post has now been updated with new information at https://thebioscope.net/2012/06/27/let-the-games-begin

It is less than a month now until the Olympic Games in Beijing begin, and for two weeks hundreds of cameras will be trained on the athletes, images of whom will be beamed out to billions. Perhaps nothing better illustrates the ubiquity, power and global shared experience that the motion picture has grown to represent from its simple beginnings in 1896 than that concentrated period, every four years, when it covers the Olympic Games, a phenomenon which likewise traces its (modern) roots to 1896.

The modern Olympic Games and motion pictures share a common heritage, beyond that shared birthdate of 1896 (motion pictures existed before 1896, of course, but 1896 was when they first made their real impact upon the world). The two phenomena grew up together, in sophistication, intention and global reach. To view the films of the early Olympic Games is to witness the growth of the medium in how it captured action and form, from analysis, to (relatively) passive witness, to a medium that shaped athletic events to its own design. We see a transition from a formality bred of militaristic roots to entertainment, art and a focus on the individual. In the words of Olympic historian Allen Guttmann (talking of modern sports overall), we see a movement from ritual to record. The survey that follows summarises the history of the Olympic Games on film throughout the silent era, that is, to 1928.

Athens, 1896

No one filmed the first Olympic Games of the modern era. The Games, which were held in Athens 6-15 April and attracted 241 athletes from fourteen nations, enjoyed some notice around the world, probably appealing as much to classicists as to athletes, but the motion picture industry was in its infancy and not as yet geared up to reporting on world news. Motion pictures had not yet reached Greece, America would really only awake to motion pictures on a screen on 23 April, with the debut of the Edison Vitascope, and the Lumière brothers – really the only possible candidates – did not think to send one of their operators to Athens. Occasionally on television you will see film purporting to show the Games of 1896. Such scenes are false – in most cases, you are being shown images from 1906.

Paris, 1900

The 1900 Games were something of a disaster after the modest triumph of Athens. Organised to run alongside the great Paris Exhibition of 1900, the Games were barely recognised as such, being so chaotically organised and poorly promoted that many of the athletes who did take part in the events (which stretched from May-October 1900) were unaware that they had taken part in the Olympics. It is no surprise, therefore, than no standard films were made of Paris Games (several films of the Paris exhibition survive, but none show the athletic contests).

However, fleeting cinematographic records do exist. The Institut Marey, the scientific institute led by Etienne-Jules Marey, who had developed the art and science of chronophotography (sequence photography undertaken for the purposes of analysing motion), decided to record some of the visiting American athletes, to compare their methods with those of French athletes. Alvin Kraenzlein (winner of gold medals for long jump, 60 metres race, 110 metre hurdles and 200 metre hurdles), Richard Sheldon (illustrated, gold medal winner in the shot put), and the legendary Ray Ewry (exponent of the now discontinued events of standing high jump, long jump and triple jump) were among those filmed. The ‘films’ are a few frames long, lasting less than a second each, yet they were enough to demonstrate the superiority of the dynamic attack of the American technique over the correct military bearing of the equivalent French athletes. These fleeting images survive today – there are examples in the National Media Museum – and illustrations from them can be found in the official report on the Games.

St Louis, 1904

Paris was a disaster for the nascent Olympic movement, but St Louis was worse. Again, they went for the convenience of being part of a general Exposition, and again the Olympic events were mismanaged from start to finish, with little sense of a Games with a distinct identity, and the distant location putting off many athletes not hailing from America. Nor, to the best of my knowledge, were any films taken on the Games. The International Olympic Committee’s site exhibits a video clip which it says shows running events from 1904 (click on the Photos section of the site), but I don’t think those are the 1904 Games (the background looks wrong), and I’ve found no evidence from catalogues of the period of any such film being taken.

Athens, 1906

Archie Hahn (USA) winning the 100 metres in 1906 (still photograph, not from a cinematograph film)

The intercalary Games of 1906 did not occur during an official Olympiad (i.e. the four-yearly period that marks when the Olympic Games are held), but this intermediary contest, designed partly as a sop to the Greeks who were disappointed that the Games were not being held permanently in Athens, was a relative success and did much to get the idea of the Olympics back on track. It also attracted the film companies. Gaumont and Pathé from France, the Warwick Trading Company from Britain, and Burton Holmes of America all made short films of the Games (we are long way yet from feature-length documentaries). The films that survive (one from Gaumont, one unidentified) emphasise the ritual, concentrating on the opening ceremonies and gymnastic displays. Individuals are lost in the mass.

London, 1908

Dorando Pietri finishing the 1908 Marathon (still photograph)

The Games started to come of age in London in 1908. Although they were again held in tandem with an exhibition, in this case the Franco-British Exhibition, for which the famous White City and associated stadium were built, this time the Games were welcomed by the organisers. The result was a popular success and a qualified triumph for sport – the qualification being necessary because the Games were marred by some bitter rivalry between America and Britain, geo-political tensions being played out on the athletics track not for the last time.

The Games were filmed by Pathé, in what seems to have been a semi-exclusive deal. The Charles Urban Trading Company filmed events outside the stadium, including the Marathon, but within the stadium it was Pathé alone, an indication of arrangements to come. Around ten minutes survive, a selection of which can be found on the British Pathe site. Basic coverage is given to the pole vault, high jump, tug o’ war, discus, water polo and women’s archery, though no names are given for athletes. But what distinguishes the 1908 coverage is the Marathon. Around half of the extant film of the Games is devoted to the race, concentrating on the Italian Dorando Pietri, who staggered over the line first, only to be disqualified because he had received help after he collapsed in the stadium within sight of the finishing line (something the film makes quite clear). For the first time on film we thrill at the sight of Olympic endeavour.

Stockholm, 1912

The Great Britain football team, gold medal winners in 1912 (still photograph)

The Stockholm Games of 1912 were the most successful yet. Twenty-eight nations, 2,407 athletes (just forty-eight of them women), a triumph of organisation, and an event followed more eagerly around the world than ever before. Responsibility for filming the Games went to the A.B. Svensk –Amerikanska Film Kompaniet, which commissioned Pathé exclusively to film a series of short newsfilms. All this footage survives in the archives of Sveriges Television. Now, at last, the athletes are named, and we get a sense of competition and achievement. In the first of two reels covering the Games held in the BFI National Archive, we see the inevitable gymnastic display, first by Scandinavian women’s team (for display purposes alone – women’s competitive Olympic gymnastics only began in 1928) followed by men’s team and individual gymnastics; the Swedish javelin thrower Eric Lemming, winner with the world’s first 60 metre throw; fencing, shot put, the 10,000 metres walk and the shot put, won by Harry Babcock of the USA. The second reel features men’s doubles tennis, the soccer tournament (Great Britain – not England – beating Denmark 4-2 in the final), Graeco-Roman wrestling, hammer throwing, the standing high jump, and the Marathon, run on an exhaustingly hot day that caused half the runners to retire. Filmed in engrossing detail, the drama of the Marathon is built up well, the tension in the sporting endeavour pushing forward the form of the film attempting to encapsulate it. The race was won by Kenneth McArthur of South Africa.

Antwerp, 1920

The Sixth Olympiad was to have been held in Berlin in 1916. Those Games were, unsurprisingly, cancelled, though film exists of German athletes training for the Games. After the war, the Games were awarded to Belgium, which perhaps was not entirely ready for the compliment after all it had been through, and the 1920 Games were hastily and cheaply organised. Despite this, the growing world interest in athletic competition had continued to grow, and there were several notable athletes who made their mark on Olympic history, including the ‘Flying Finn’ Paavo Nurmi, America’s Charley Paddock winning the 100 metres, and France’s Suzanne Lenglen at the start of gaining worldwide fame as a tennis player. Sadly, only a few newsreels were made of the events. The IOC website features film of the opening ceremony, American hammer thrower Patrick McDonald, and one of the stars of the Games, 14-year-old American diver Aileen Riggin.

Paris, 1924

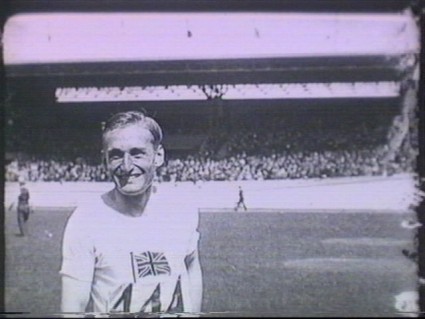

Harold Abrahams winning the 100 metres, from Les Jeux Olympiques Paris 1924 (frame still)

And then we come to 1924. The second Paris Games have become familiar to many through their recreation in the 1981 film Chariots of Fire. There is a particular thrill in seeing the two British athletes whose fortunes are covered by the Oscar-winning film, Eric Liddell and Harold Abrahams, turning up for real in such detail. For this was the first time where we had a feature-length documentary dedicated to the Games. Strictly speaking, the film produced by Rapid-Film of France was a series of two-reelers dedicated to different sports, including those from the first Winter Games, held in Chamonix. Nevertheless, it was also compiled as a complete film, Les Jeux Olympiques Paris 1924, a daunting three hours long (unexpectedly, it is preserved in its entirety by the Imperial War Museum Film and Video Archive).

[Update (September 2008): Les Jeux Olympiques Paris 1924 is no longer held by the IWM, having been passed to the International Olympic Committee. An incomplete copy of the film is held by the British Film Institute]

Viewing the film in one sitting is something of a challenge, but individual events are never less than efficiently portrayed (aside from some tedious wrestling) and occasionally marvellously so. Particularly thrilling is the football, where the Uruguyan gold medal winners demonstrate a level of tehnical accomplishment light years ahead of the sturdy endeavours of the European teams. The 100 metres, won by Abrahams, is a highlight, with choice details such as the athletes digging holes in the track for their heels. Slow motion is used artfully (particularly for the 3,000 metres steeplechase). The Marathon is a tour de force, a real drama in itself, with such carefully observed details as the anxious look of officials at the drinks stations (and how delightful in itself that the French served wine as well as water). Few who were there can have forgotten Neil Brand’s bravura accompaniment to the 1924 Marathon at Pordenone in 1996, when the Giornate del cinema muto put on a special programme of silent Olympic films.

Star athletes on show include Nurmi, his great Finnish rival Ville Ritola, the Americans Jackson Scholz (sprinter) and Helen Wills (tennis player), but disappointingly all we see of the future Tarzan Johnny Weismuller is his submerged figure in long shot as he raced to fame as a swimmer. Les Jeux Olympiques Paris 1924 (produced by Jean de Rovera) is no film masterpiece, but as a sporting record, it captures greatness.

Amsterdam, 1928

Lord Burghley, winner of the 400 metre hurdles, from Olympische Spelen (frame still)

The last Olympic Games of the silent film era were held in Amsterdam in 1928. The Games were by now thoroughly established as an event of worldwide significance. The idea of a film dedicated to the Games had also been established, though the problems that beset the 1928 film, Olympische Spelen, were such that it was barely seen, and it remains little known. The history is complicated, but essentially in 1927 the Dutch Olympic Committee approached a federation of Dutch film businesses to mange the filming of the Games. Negotiations fell down over financial considerations – and because the Dutch commitee was, at the same time, negotiating with foreign film companies. Eventually they did a deal with the Italian company Istituto Luce. For the first time a director was chosen with an ‘arthouse’ pedigree (Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia of 1936 was neither the first Olympic film nor the first with a notable director, as some histories would have us believe). The director was the German Wilhem Prager, who had enjoyed notable success with the 1925 kulturfilme sports documentary Wege zu Kraft und Schönheit (Ways to Strength and Beauty), in which Riefenstahl takes a fleeting acting role.

Prager’s film (preserved in the Nederlands Filmmuseum) is no more than efficient, though it does have some innovations such as having the names of athletes in some distance races appear as captions alongside them as they run. The film shows us Nurmi and Ritola once more; Boughera El Ouafi, the Algerian-born (but running for France) winner of the Marathon; the ebullient Lord Burghley (played by Nigel Havers in Chariots of Fire) winning the 200 metre hurdles; and Japan’s triple jumper Mikio Oda, the first Asian athlete to win an Olympic gold medal. But alas, owing to the considerable mishandling of the whole affair by the local Olympic Committee, Dutch exhibitors boycotted the official film, and hardly anyone saw it.

Das Weiss Stadion, from http://www.filmportal.de

There was also a feature-length film made of the 1928 Winter Olympics at St Mortiz, Das Weisse Stadion. Directed by Dr Arnold Fanck (the man who discovered Leni Riefenstahl as a film actress) and Othmar Gurtner, it was made for Olympia-Film AG of Zurich, and edited by the great Walter Ruttmann. However, Fanck appears to have viewed it as a chore and to have filmed it in a perfunctory manner. Only two cameramen were used, which would have hampered its coverage to a serious degree – which we have to assume, since the film is not known to survive.

Olympic drama

Johnny Weissmuller (left) and Duke Kahanamoku

Finally, to complete the history, note must be made of those Olympic athletes of the silent era who went on to appear in fiction films once their fame had been established through sporting endeavour. Johnny Weissmuller, star of the 1924 and 1928 Games, of course went on to eternal fame as Tarzan. The American sprinting hero of 1920 and 1924, Charley Paddock, starred in Nine and Three-Fifths Seconds (1925), The Campus Flirt (1926), The College Hero (1927), High School Hero (1927), and (guess what) The Olympic Hero (1928). The Hawaiian swimmer Duke Kahanamoku was in five American Olympic teams between 1912 and 1932, but could also be seen swimming and acting in Adventure (1925), Lord Jim (1925), Old Ironsides (1926), Woman Wise (1928) and The Rescue (1929). Buster Crabbe, like Weissmuller a swimming champion in 1928, went on to become Flash Gordon, while Herman Brix (shot put silver in 1928) went on to become Tarzan and as Bruce Bennett starred in many films, including Treasure of the Sierre Madre.

Finding out more

There are few histories of Olympic film, and where these do exist they either get elementary facts wrong or assume that everything started in 1936 with Olympia. As the above should indicate, there was a rich history of Olympic filmmaking going back to 1900, and many of the innovations in Olympic film which we might associate with later times had been achieved before films gained sound. One exception is Taylor Downing’s Olympia, in the BFI Film Classics series, which has a brief but reliable history of Olympic film prior to 1936. And if you can get hold of it, my long article ‘Sport and the Silent Screen’ in Griffithiana 64 (October 1998) has much of the history recounted above, though I have now had the opportunity to correct some facts, and amend some opinions. The best general book on the Olympic Games, by several miles, is David Wallechinsky and Janine Loukey’s The Complete Book of the Olympics, a sport-by-sport historical survey which also includes (if you look hard) information on the film careers of some Olympic athletes.

The easiest place to see some of the films is the International Olympic Committee’s www.olympic.org site. Under the Olympic Games section there is a mini-history of each Games from 1896 (excluding 1906), and in each of these sub-sections at the bottom of the page there is a Photo Gallery which (if you click on any image) also contains some video clips. Information on the Olympic Games generally is all over the place, of course, but for the researcher particular attention should be drawn to the LA84 Foundation site, an astonishingly rich resource originally create to commemorate the 1984 Los Angeles Games but now providing free access to a vast range of digitised historical documents on all of the modern Games (including, for examples, the official reports).

Some other sites of interest: The Olympic Studies International Directory, a directory of research in all aspects of the Olympic Games; the Olympic Television Archive Bureau, or OTAB, the company which markets Olympic footage from all periods; and the rather wonderful www.dorandopietri.it, which celebrates (in English and Italian) the life of the Marathon runner the centenary of whose triumph and disaster is marked this year.