E.A. Dupont directing Das Alte Gesetz, from http://www.juedischesmuseum.de

Every Pordenone Silent Film Festival has the one outstanding title, a feature generally previously neglected or unknown, whose exhibition here revives its reputation and gets everyone talking. This year the palm d’or undoubtedly went to E.A. Dupont’s Das Alte Gesetz (1923). Ewald André Dupont has had a revival in reputation of late, owing to the visibility of his late British silents Moulin Rouge (1928) and especially Piccadilly (1929), and in the reference books he always gets a warm mention for Varieté (1925), one of the cast-iron classic silents, and a shake of the head in sorrow for the sharp dip in his career that occured with the arrival of sound.

Das Alte Gesetz has been more listed in filmographies than seen, but it is close to a masterpiece. Set in the mid-nineteenth century, it tells the tale of a young Jew, Baruch (Ernst Deutsch), who breaks away from his Orthodox village background and stern rabbi father to become an actor in Vienna. So it is reminiscent of The Jazz Singer in theme, but it is the technique and style that distinguish the film. Dupont knows how place people within the frame, how they move within that space, how to capture the tensions between people, how to film intensity. With the help of superb sets by Alfred Junge, he deftly contrasts the humble, ritualised Jewish life with the elegant, no less ritualised Viennese society, personnified by Henny Porten poignantly playing an archduchess attracted to Baruch. The portrait of theatrical life, from ramshackle touring theatre with its wobbly sets to the formalities of the Burgtheater are beautifully drawn, and Deutsch (excellent) ably persuades us of an adolescent enthusiasm for performance which gradually reveals real dramatic talent. It is the resolution of his new world with his past that forms the core of the film, and his stern father’s painful acceptance of his son’s new life is memorably drawn by Avrom Morewsky. Most touching is the scene where he apprehensively picks up a book of Shakespeare’s plays (we see Baruch in Romeo and Juliet and Hamlet), which he tries to open back-to-front (i.e. as though a Jewish religous text) before reading it and discovering that the truths that his son understands are not so far from those that govern his life. The film looks superb (photography by Theodor Sparkuhl) and ought eventually to find a DVD release. It certainly merits screenings at other festivals.

Annie Bos, from http://www.stadstheater.nl

Das Alte Gesetz was heady stuff for 9.00am. It was followed by four titles featuring the great star of Dutch silent cinema, Annie Bos. No, I hadn’t heard of her either. She was popular through the teens in Holland, graduating from slight social comedies to melodramatic diva roles in imitation of the Italian actresses Lyda Borelli and Francesca Bertini. She started out in comedies about two naive Dutch girls, Mijntje and Trijntje. In Twee Zeeuwsche Meisjes in Zaanvoort (1913) we see a somewhat plump Annie as one of the duo who go to the seaside and… well, that’s about it, they go to the seaside, and they improvise some comedy, and passers-by in the background stare on in amusement. Boerenidylle (c.1914) is similarly unencumbered by narrative. Annie is courted by her farmhand boyfriend, nothing dramatic happens at all, and the scenery is beautiful. Full-on drama comes with the delirious De Wraak van het Visschersmeisje (The Revenge of the Fisherman’s Girl) (1914). Exploiting the availability of an exotic dancer who employed snakes in her act, this impressively ludicruous mini-drama has two characters savaged by a quite sizeable python, which brightened up the audience no end. The feature-length Toen ‘t Licht Verdween (1918) showed a slimmed-down Annie in full diva mode, as a woman whose growing blindness causes her the loss of her composer husband, while a hunchback organist who truly loves her tries to save her, only for her life to end in suicide.

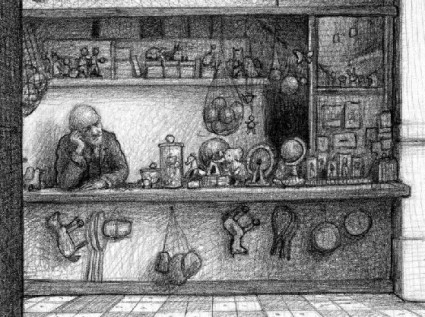

We should turn to René Clair for some light relief, but alas in the 1920s he was still finding his way as a filmmaker, and Le Fantôme du Moulin Rouge (1925) was disappointingly conventional and ponderous. It tried to introduce fantasy elements – the hero is able to float disembodied through Paris, viewing events but unable to affect them – but it was uncertain whether to adopt a light or serious tone. Starewitch also seemed a little off-form with Liliya (1915), a curious attempt to illustrate the invasion of Belgium in 1914 with insects, and Dans les Griffes de l’Araignée (1920), a rather confusing drama involving spiders.

To round off the day, here’s a telling scene taken in the early morning, before the festival office had been opened, but with the wifi service switched on. From right to left, Dennis Doros of Milestone Films, Thomas Christensen, curator at the Danish Film Archive, and Minnie Hu, a student at the University of Washington and journalist for the Seattle China Times.