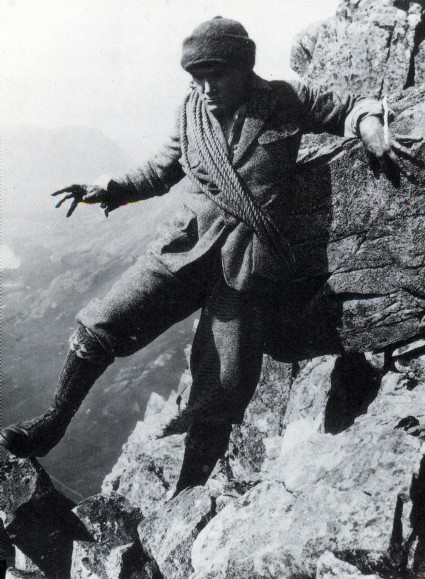

Sir Harry Lauder Visits the Regent Picture House (1928), from the Scottish Screen Archive

I am pleased to be able to offer for you a piece written especially for The Bioscope by Janet McBain, Curator of the Scottish Screen Archive at the National Library of Scotland. Janet’s subject is the local topical. You will have to search very hard in the film history literature to find anything written on the local topical, but go to any UK film archive and you’ll find them in abundance. For the local topical was a local newsreel – filmed locally (often by a cinema’s projectionist) and shown locally. Such films, which flourished in particular in the 1910s and 20s, showed parades, civic marches, works’ outings, visits of dignitaries, or often simply people miling about in the street, filmed by a touring showman who would then tell you to turn up at the ton hall that evening, where you would be guaranteed to see yourself on the screen.

Just such films have become known to more than archivists of late, thanks to the sterling work done by the British Film Institute and the National Fairground Archive to promote the Mitchell & Kenyon collection of films predominantly showing working class life in English northern towns in the 1900-1910 period. M&K were commissioned to film local parades, galas, football matches and such like, and would indeed film people in the streets to encourage them to see the film show in the evening. Mitchell & Kenyon have achieved modern fame, through books, a television series and DVDs. But there were many other such films, as Janet McBain’s piece informs us.

The world of local topicals: observations on life after Mitchell and Kenyon through local films made for the Regent Cinema, Glasgow in the 1920’s

As we have seen with the Mitchell and Kenyon film collection early independent exhibitors, in the first decades of the moving picture, clearly understood the appeal and the business value of ‘ local films for local people’. With marketing slogans such as ‘Come and see yourselves as others see you’ they understood their audiences and what they wanted to see and exploited this with flair and showmanship learned out on the road with the travelling fairground shows.

Still very much in the shadow of these Edwardian films and ripe, I would suggest, for re-discovery are local topicals from succeeding decades. Still presented and marketed as ‘see yourself on the silver screen’, but offered by exhibitors running permanent, fixed site shows from 1911/12 onwards.

There are literally hundreds of these post-M&K films in the UK’s moving image archives dating from just before the Great War to the decades after World War 2. (Scottish Screen Archive has over 500 titles in its collection alone). They are classified inconsistently as topicals, local topicals or local newsreels. The fact that we in the archive community still do not have a standardised genre or classification term is indicative of the lack of understanding of, or attention to, this material.

When talkies came along in the late 20’s the local topical continued – but remained silent. Due in part to shortage of film stock during the Second World War they disappear, only to re-emerge in the post-war era – still mostly silent. But by the end of the 1950’s, with changes in cinema-going habits and the demise of many of the independently owned cinemas the local topical all but disappeared.

Typical of the content of these films are crowd pulling events: gala days, parades, local festivals and holidays, unveiling of war memorials, sports meetings – events that would get local people out onto the streets and in front of the camera lens.

We still know relatively little about audience reception, means of production or how the exhibitors financed and publicised these films. There is evidence that some exhibitors and cinema managers shot the films themselves, other times that they engaged newsreel and production professionals to make them.

Whatever and whoever he was the cameraman would be instructed by the exhibitor to get in as many close-ups of faces in the crowd as possible. Hence the frequent use of the panning shot, very much the hallmark of the local topical, to maximise your audience who would be enticed into the picture hall a few nights later with the prospect of seeing themselves on the big screen.

Local topicals sit somewhat uncomfortably between news reportage and actuality. They can be seen as both … and neither. They are not hard news per se, but they cover newsworthy events within a local sphere. They are intended as promotional tools and this influences content, which in turn robs them to a degree of the objectivity of the actuality. Perhaps the local topical could be described as a discrete genre in its own right.

Two examples of local topicals discovered recently by Scottish Screen Archive illustrate the fudged line between news and actuality – the grey zone in which sits the local cinema newsreel.

They have a consistent theme. Both were commissioned by William McGaw, manager of the Regent Picture House in Renfield Street in Glasgow, one of the first purpose built cinemas in the city centre. McGaw was a enthusiastic publicist and won many trade awards for showmanship during his career.

Both films were shot on the occasion of special screenings at the Regent with the personal appearance of a film star, illustrating another fascinating feature of the local topical, that of recording the history of cinema-going itself.

Both films were intended to serve as local topicals – to be shown in the picture house, and to engage the audience through recognition, of themselves and their friends, on the screen. The Minute Books for the Regent’s proprietary company give accounts of the manager’s application to the Directors’ to approve this advertising strategy.

The two films differ, however, in editorial approach.

Vera Reynolds Visits Regent Picture House (1926)

The first one records Vera Reynolds, young American actress, making a personal appearance at the cinema in September 1926 for the Scottish premiere of The Road to Yesterday. It looks like a newsreel item. The focus is on the celebrity, it is a two-camera shoot suggesting it was made by a professional unit, possibly local stringers from Gaumont’s or Pathe’s Glasgow office. Reynolds herself is very camera aware and is the star of the film in every sense.

The second title comes two years later on 5th October 1928 with Sir Harry Lauder’s personal appearance at the cinema for the premiere of Huntingtower, George Pearson’s adaptation of the novel by John Buchan and in which Lauder took the leading role as Glasgow grocer Dickson McCunn. We know from reports in the trade press that the topical was shot by James Hart, projectionist at the Grosvenor Cinema, a small picture house in the west end of the city. At the time Hart made this film for McGaw and the Regent his own locals, under the banner Grosvenor Topical News, were appearing on screen on an almost weekly basis. Lauder travelled specially from Edinburgh on a Friday morning to see Huntingtower for himself for the first time. Hart’s topical was screened at the first house on that same evening and before every performance of the big picture during the weeks thereafter.

Sir Harry Lauder Visits the Regent Picture House (1928), Lauder himself in the centre

Of the two films Hart’s footage is more quintessentially recognisable as a local topical. He foregrounds the future audience with long tracking shots and pans of the cinemagoers and the crowds waiting on the street outside the picture house, almost overshadowing the appearance of the star. Lauder and four boys from the cast of Huntingower posed in the entrance of the cinema are on screen for maybe a third of the film. Hart gives us intertitles identifying the participants, including McGaw the cinema manager. He understood the rationale for the film, arguably more so than the professional newsreel maker who assembled the earlier Reynolds film. In this one she is undoubtedly the star taking up all the screen time. There are no identifiable shots in this film of the local people – they are not visible on camera as individuals.

Both films have been preserved by Scottish Screen Archive and can now be viewed along with other local topicals online at www.nls.uk/ssa.

Also another of the writer’s favourites – illuminating aspects of cinema history – is also now available online:

There are hundreds more local topicals awaiting re-discovery in the nation’s archives – come and find them!

Janet McBain

Curator

Scottish Screen Archive,

Glasgow

December 2009

As pointed out, you can see the two Regent films at the Scottish Screen Archive’s excellent site (where there are over 1,000 film clips freely available to view), the subject of

a Bioscope post a year or so ago. Other UK film archives with local topicals can be found via the

Film Archive Forum site, or you can see examples on

Moving History, a sampler site of films from archives around the UK. For example, check out the North West Film Archive’s

Milnrow and Newhey Gazette (1913) or the Media Archive of Central England’s

The Meet of the Quorn Hounds 1912, each of which is accompanied by a mini-history of the local topical genre..

If by chance you haven’t come across Mitchell & Kenyon as yet, the BFI provides a handy guide which gives an overview of the collection, the history of their production, images, and links to DVDs and books, particularly Vanessa Toulmin, Simon Popple and Patrick Russell (eds.), The Lost World of Mitchell and Kenyon: Edwardian Britain on Film (2004). And there are numerous examples of M&K films available to videw for free on the BFI’s YouTube channel.