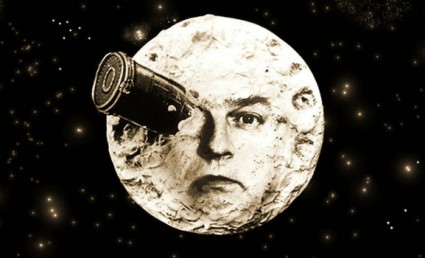

Cover for Photoplay, January 1927

As we’ve said before, while there is an embarrassment of riches when it comes to digitised historic newspapers now available online, for the specialist things are tougher and those interested in the study of film history have bemoaned the absence of the major trade paper and fan magazines in digitised form.

But while most of us have done the moaning, others have been acting. Today the Media History Digital Library project was announced. This announces itself as a major conservation and access project for histoical printed materials related to cinema, broadcasting and recorded sound. Concentrating on American media industry journals, and with recourse to private funds, the project has been established by film archivist and historian David Pierce. The project has hugely ambitious plans, but it has kicked off with eight volumes (covering four years) of Photoplay, and one volume each of Motion Picture Classic (1920) and Moving Picture World (April-June 1913), taken from the collection of the Pacific Film Archive. All have been made available via the Internet Archive, as follows:

Motion Picture Classic (Volume 9 – 11 (1920))

The Moving Picture World (Volume 16 (Apr. – Jun. 1913))

Photoplay (Volume 28 – 29 (Jul. – Dec. 1925))

Photoplay (Volume 30 – 31 (Jul. – Dec. 1926))

Photoplay (Volume 31 – 33 (Jan. – Jun. 1927))

Photoplay (Volume 33 – 34 (Jan. – Jun. 1928))

Photoplay (Volume 35 – 36 (Jan. – Jun. 1929))

Photoplay (Volume 36 – 37 (Jul. – Dec. 1929))

Photoplay (Volume 37 – 38 (Jan. – Jun. 1930))

This link will take you to all of the documents on one page: Media History Digital Library

As said, this is just the start. The Media History Digital Library’s press release outlines the ambitions:

The history of American media industries exists in the magazines of the day, but is largely inaccessible. Primary materials, such as Exhibitors Herald World and Photoplay are of significant research value to media scholars, historians, and the general public; however, use of these resources is severely limited by necessary noncirculating access restrictions and/or the lack of indexing or fifinding aids.

Using private funds, a pilot project is currently underway to digitize 300,000 journal pages, including volumes of Moving Picture World and Photoplay, and a range of additional materials to appeal to varied research interests.

Several major libraries and the owner of the largest private collection of such materials are participating in the pilot.

The goal of the Media History Digital Library project is to establish additional partnerships with libraries and archives for a joint digitization project to conserve and provide broad free access to these important resources.

These are the the titles that the project is targeting:

Industry Magazines – Billboard, Box Office, Cine-Mundial, Daily Variety, Exhibitor’s Herald, Exhibitor’s Trade Review, The Film Daily, The Film Index, The Hollywood Reporter, Motion Picture Daily, Motion Picture Herald, Motion Picture News, Motography, The Moving Picture World, Radio Broadcast, Radio Daily, Talking Machine World, Variety

Company Magazines – The Lion’s Roar, Publix Opinion, RCA News, Radio Flash, Reel Life, Universal Weekly

Fan Magazines – Motion Picture Classic, Motion Picture Magazine, Motion Picture Digest, Radio Mirror, Screenland, Shadowplay

Technical Journals – American Cinematographer, American Projectionist, The International Photographer, International Projectionist, Motion Picture Projectionist, Projection Engineering, Radio Engineering, Sound Waves, Transactions of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers

Well, that should keep us all busy. Of course this will take time and money (it’s costing 10 cents a page at the moment), but a model has been established whereby institutions holding such collections can work together efficiently, avoiding duplication of effort and adhering to common standards and formats to provide researchers with the best possible search and access opportunities.

The project outline is as follows:

- Each archive or library agrees to offer its pre-1964 public domain journals for digitization.

- Each archive or library will provide an inventory of its holdings, perform condition inspections and pack selected materials for shipping. The project will pay transportation and reasonable insurance both ways. Any funds for digitization will be welcome, but not required.

- Each digitized volume will have an inserted page with the name and logo of the organization contributing the original volume, the organization that manages that part of the workflow, and the funder.

- The Internet Archive will execute some of the digitization and will host the master and derivative format access files.

- In return for contributing materials, each organization is entitled to receive copies of all digital files for any non-commercial purpose including hosting on their website.

- David Pierce will raise financial support for the project as well as perform copyright searches.

As some may have noticed from the Bioscope’s recent survey of silent film journals online that the first fruits of this project have been available on the Internet Archive for a few weeks now, but the formal announcement of the project was held back while some digitisation issues were resolved. But Leonard Maltin spilt the beans in his enthusiastic blog post earlier today, so David Pierce went public today.

What can one say? This is a sensational development, with a myriad of opportunities for the researcher – not just in film studies, but social history, media history, histories of communications and technology, fashion history, genealogy, advertising studies, gender studies and so much more. But there is much that we can do to help. There’s the invitation for collection owners to participate in the project, but also each one of us can prove the value of this project by just using the documents. Download them, study them, blog about them, cite them in papers, curate them – demonstrate that this is what we need. The best way of saying thank you is to start using them. Go explore.