Wednesday, June 11

Keynote address

Jane Gaines – Women and the Cinematification of the World

11:00–12:45

Parallel Sessions 1.1

National and Transnational

Rosanna Maule – Feminist Film History and the (Un)problematic Treatment of Trans-nationalism in Early Cinema

Christine Gledhill – Mary Pickford: Emerging Stardom and Transnational Circulation

Sanjoy Saksena – Image of Women in Colonial and Post-Colonial Indian Cinema

Phil Powrie – Josephine Baker and Pierre Batcheff in La Sirène des tropiques (1927)

Sharpened Pencils

Domenico Spinosa – The didactic-instructive task of cinema (1907-1918) in the Italian women writings

Luca Mazzei – Going to movies wearing a skirt and handling a pen. Women writing about cinema 1898-1916

Luigia Annunziata – Matilde Serao and the cinema

Louis Pelletier – Ray Lewis and the Birth of Canadian Film Culture

Germaine Dulac

April Miller – Pure Cinema, Pure Violence: Murder as Avant-Garde Aesthetic in Germaine Dulac’s La Coquille et le Clergyman and La Souriante Madame Beudet

Tami M. Williams – An Invitation to a Voyage: Cross medial spatial metaphors, modes of transport and sexual liberation in the cinema of Germaine Dulac

Catherine Siberschmidt – The concept of spectatorship in Germaine Dulac’s film theory

Sarah Keller – “Optical Harmonies”: Sight and Sound in Germaine Dulac’s Integral Cinema

13:45–16:00

Parallel Sessions 1.2

Conceptualizing “Female Pioneers”

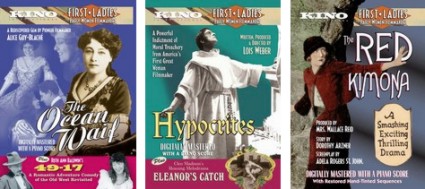

Shelley Stamp – Lois Weber’s ”Feminine Hand” at Rex

Karen Ward Mahar – Working Girls: The Masculinization of American Business in Film and Advice Literature in the 1920s

Isabel Arredondo – Forgetting Women Film Pioneers: Juliet Rublee and the Myth of the Avant-Garde

Mark Lynn Anderson – The Real Dorothy: Mrs. Wallace Reid, the Newspaper, and Feminist Film Historiography

Monica Dall’Asta – What Means to Be a Woman: Theorizing Feminist Film History Beyond the Essentialism / Constructionism Divide

Case Studies in Stardom

Tijana Mamula – Ideal Situation: Projecting Knowledge in Prix de Beauté

Miya Tokumitsu – f(Swoon): The Function of the Female Swoon in Silent Film

Nicole Beth Wallenbrock – The Hollywood Flapper dies an Expressionist Death (Louise Brooks in Pandora’s Box)

Galen Wilson – Performance of Anxiety: Les Vampires and the Crisis of Gender in the Fin-de-Siecle

Hélène Fleckinger -“The wicked woman” On the character of Irma Vep in Les Vampires of Louis Feuillade

Authorship and Screenwriting

Vincent L. Barnett – The Novelist as Hollywood Star: Author Royalties and Studio Income in the 1920s

Alexis Weedon – Elinor Glyn the Author On Page and Screen

Stephan Michael Schröder – The conditions of freelance script writing – example Harriet Bloch

Claus Tieber – Between Sentimentalism and Modernity: The narrative structure of Frances Marion’s screenplays

Anke Brouwers – The Name Behind the Titles: Women, Authorship and Silent Screenwriting

Thursday, June 12

9:00–10:45

Parallel Sessions 2.1

Cross-Gender Casting and Lesbian Characters

Astrid Söderbergh Widding – Flickan i frack – A Case of Cross-Dressing

Laura Horak – Edna/Billy Foster, the Biograph “Boy”

Fiona Philip – Veiled Disclosures and ‘Speaking Back’: Borderline (1930) and the Presences of Censorship

Susan Potter – Opening up Pandora’s Box

American Stardom

Mary Desjardins – A Method to this Madness? The Myth of the Mad Silent Film Star

Charlie Keil – ’Studio Girls’: Female Stars and the Logic of Brand Names

Jeannette Delamoir – Mary Pickford and Louise Lovely: The silent motion-picture star in the age of reproduction

Tricia Welsch – From Pratfalls to Glamour: Gloria Swanson at Triangle

(Re)discovering Female Filmmakers 1

Nathalie Morris – “Alma isn’t Talking”: The Early Career of Alma Reville aka Mrs Alfred Hitchcock

Claudia Preschl and Elisabeth Streit – Making Noice (Proud to be loud). Women in the Silent-Period of Austrian Film History

Anne Bachmann – Parallel stories? Ebba Lindkvist’s brief career and the film version of a

theatrical play

Annemone Ligensa – “A Cinematography of Feminine Thought”: The Novel The Dangerous Age (1910) by Karin Michaelis and Its Filmic Adaptations

Parallel Sessions 2.2

(Re)considering Genres and “Feminine Tastes”

Lea Jacobs – On Hating Valentino: The Rejection of the Romantic Drama in the American Cinema of the 1920s

Annette Förster – Humorous reflections on acting, filmmaking and genre in comic film productions by Adriënne Solser, Musidora, and Nell Shipman

Kristen Anderson Wagner – “Ever on the Move”: Silent Comediennes and the New Woman

Fashion and Fandom

Mila Ganeva – Women between Screenwriting and Fashion Journalism: The Case of Ruth Goetz

Therése Andersson – Beauty Box – Film Stars and Beauty Culture in Early 20th Century Sweden

Andrea Haller – “Flimmeritis” and Fashion – Early intermedial practices of female movie fandom in Imperial Germany

Lisa Stead – “It costs nothing to wish!” Female Fan Writing and Self-Representation in the British Silent Cinema

(Re)discovering Female Filmmakers 2

Marcela de Souza Amaral – Alice Guy and the narrative cinema

Mike C. Vienneau – The discursive Art of Alice Guy: The cinema and the feminine silent word

Jindiška Bláhová – “The lady crazy about film” – demystifying Thea ervenková, the mystery woman of the early Czechoslovak cinema

Micaela Veronesi – A woman wants to create the world. Umanità by Elvira Giallanella

14:00–15:45

Parallel Sessions 2.3

Stardom and Intermediality

Anne Morey – Geraldine Farrar: A Film Star from Another Medium

Victoria Duckett – A new anachronism: Sarah Bernhardt and the modern theatrical film

Elena Mosconi – The Star as an Artist: Italian Divas between Symbolism and Liberty

Maria Elena D’Amelio – Damned Queens. Two case studies on the dark ladies in Cabiria and Maciste all’inferno films

(Re)discovering Female Filmmakers 3

Begoña Soto Vázquez – How to research the exception: the power of the unknown

María Cami-Vela – Women, bullfighters and identity in Spanish Silent Cinema: Musidora

Bárbara Barroso – Virgína de Castro e Almeida: writing, producing and envisioning film

Nadi Tofighian – Isabel and José – the pioneer tandem filmmakers of the Philippines

More than Filmmakers

Anne Marit Myrstad – Film censorship, morality and female identity: Fernanda Nissen, a case study

Joshua Yumibe – The Gendering of Color and Coloring of Films: Female Film Colorists of the Silent Era

Christopher Natzén – Greta Håkansson – a female conductor in a time of change during the transition to sound film in Sweden 1928-1932

Tony Fletcher – Laura Eugenia Smith and the Biokam Films

16:15–18:00

Parallel Sessions 2.4

Film Festivals and Screening Networks

Kay Armatage – Women’s Cinema, Film Festivals and Their Contribution to Women’s Film History

Ingrid Stigsdotter and Kelly Robinson – ‘Clowning Glories’: A Case Study of a Festival Programme and its Audiences

Rebeca Ibanez-Martin and Andrea Gautier Sansalvador – Women as Archivers of Films Made by Women: the Project of Envideas

Russian Pioneers

Dunja Dogo – Re-editing History in the Works of Esfir’ I. Šub (1927-30)

Ilana Sharp – Esfir Shub’s Costructivist Non-Fiction Film and Soviet Silent Cinema

Lauri Piispa – Vera Kholodnaia: Queen of Screen, Slave of Love

Michele Torre – A woman of all trades: Zoia Barantsevich, a pioneer in early Russian cinema

Asta Nielsen

Ansje van Beusekom – Asta Nielsen in the Netherlands in 1920

Annette Brauerhoch – Between Pleasure and Pain: Asta Nielsens Acting Acts

Heide Schlüpmann – Playing History – Asta Nielsen in Early Cinema

Karola Gramann – Screening and discussion

Friday, June 13

9:00–10:45

Parallel Sessions 3.1

Three Histories, One Archive

Jennifer Horne – Premediations: Previewing for Better Motion Pictures, 1916-1930

Mark Garrett Cooper – The Universal Women: An Institutional Explanation

Richard Abel – Unexplored Margaret Herrick Library Resources, 1910-1916

Chinese Stardom

Yiman Wang – Between “Yellowface” and “Yellow Yellowface” – Anna May Wong and Her Chinese Audience during the Interwar Era

Erin Kelley – Dance, Stardom, and the Trans-National Celebrity Status of Anna May Wong

Qin Xiqing – Pearl White and the New Female Image in Chinese Silent Cinema

Yuan Chen – Wang Hanlun, a ‘successful’ Runaway Nora in Early Chinese Film Industry

Ruixue Jia – Silence can kill: rethinking Rua Ling-yu’s tradgedy

Images of Women

Constance Balides – Moralizing Typologies to Sociological Personalities: Delinquent Women in Early Social Problem Films

William Van Watson – Enrico Guazzoni’s Marcantonio and Cleopatra: The Feline-Feminine Construct and the Colonial Dangers of Heavy Petting

Selin Tüzün Gül – From stage to the screen: Actresses as one of the symbols of Turkish modernization project

Tommy Gustafsson – The Significance of the New Woman in Swedish Silent Film

11:15–13:00

Parallel Sessions 3.2

Politics of Ethnicity

Denise McKenna – What Happened to Myrtle? Latina Stars in Early Hollywood

Ora Gelley – Race and Gender in D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915): Patterns of Narration and Vision

Nina Cartier – I Get Lifted?: Delineating Uplift’s Restrictions Upon Black Female Desire in Silent Era Race Films

Kyna B. Morgan – The First African American Woman Film Producer: Maria P. Williams and The Flames of Wrath

European Stars and Audiences

Dominique Nasta and Muriel Andrin – Engaging National Emotions on Screen: European Silent Women in “strikingly effective” Melodramas

Anna Cabak Rédei – Garbo as ’Greta’ in Pabst’s The Joyless Street (1925)

Irina Novikova – Female Stars of Cinematic Peripheries – Lilita Berzinja (Latvia)

Silvia Horváth – Feminine (self-)staging in the Hungarian Silent Film of the 1910th

Strike a Pose: Female Models and Magicians

Cynthia Chris – Censoring Purity

Pierre Chemartin and Nicolas Dulac – The pose as performance: Early cinema acting and the female stereotype

Matthew Solomon – Women and the Trick Film

An extraordinary line-up indeed. And here are the films scheduled for evening screenings, with the conference organisers’ notes and comments. Note in particular the premiere of the restoration of the recently rediscovered Mary Pickford title, The Dawn of Tomorrow:

LA RUSE DE MISS PLUMCAKE / MISS PLUMCAKE’S TRICK (France, 1911)

35mm b/w print from the Nederlands Filmmuseum

180 meters, 5 mins (18fps)

Dutch inter-titles

Prod: Pathé Frères / SCAGL

Director: Georges Monca

Script: unknown

Cast: Mistinguett, Andree Pascal, Charles Lorrain

This comedy offers us the music-hall star and future ‘queen’ of the revue, Mistinguett, in the role of a maid that is mistaken for her American mistress while visiting Paris. Mistinguett makes a parody of the

attractiveness of American women and lampoons Parisian men’s idolatry with them. The film’s inclusion in the program serves three purposes: first, because the print is incomplete, it may be taken as an example of a fragment, one of the core topics of this conference; second, bringing the existence of this rare print of a Pathé-SCAGL comedy with Mistinguett to the attention of feminist film historians; and third, calling attention to Mistinguett’s significance to the relations between French music-hall and cinema in the early 1910s, which deserves more research.

DIE LANDPOMERANZE / THE UNWIELDY COUNTRY WOMAN (Germany, 1917?)

35mm (Desmet method) colour print from the Nederlands Filmmuseum

540meters (ca)., 26mins (18fps)

German intertitles

Prod: Treumann-Larsen Film GmbH

Director: Dr. R. Portegg aka Rosa Porten and Franz Eckstein

Script: Rosa Porten

Cast: Rosa Porten (Isa), Franz Verdier (Caspar Freiherr), Max Wogritsch (Jürgen von Oesterlingk)

Isa’s father, a wealthy gentleman of the countryside, wants her to marry Jürgen. However, Jürgen is rather prejudiced towards country women. Furthermore, he is attracted to a rich girl from the city. Upon hearing this, Isa, who doesn’t want to get married anyway, swears to teach Jürgen a lesson. For this purpose, she leaves her house and applies for a job (disguised as a boy) at Jürgen’s household. This fast-paced comedy, written and directed by Rosa Porten herself, appears in almost no written sources. It is therefore no surprise that this film was lost for many years, until this incomplete print appeared in the Nederlands Filmmuseum collection, carrying the original German titles. Die Landpomeranze has been preserved in 2008 in order to be presented for the very first time at this conference. Given the impossibility to complete the missing ending, due to complete lack of written sources, the preserved print has an open end, in hope that the missing reel(s) get discovered somewhere in the future.

Trailer DIE GESUNKENEN / THE SUNKEN (Germany, 1925)

35mm b/w print from the Nederlands Filmmuseum

65 meters, 3 mins (18fps)

German inter-titles

Prod: Aafa Film

Director: Rudolf Walther-Fein

Script: Ruth Goetz and Leo Heller, based on the novel by Luise Westkirch

Cast: Asta Nielsen, Olga Tschechova, Hans Albers, Wilhlem Dieterle, Otto Gebühr

Dutch trailer from the presumed lost Asta Nielsen film Die Gesunkenen (1925), a drama based on a scenario by Ruth Goetz after the novel Diebe (Thieves) by Luise Westkirch. The Dutch censorship board noted about the film (2340 meters, + 117 minutes): ‘rough milieu’, ‘cocaine abuse’, ‘prostitution’, ‘ladies and gents of suspect repute’. In addition to Nielsen, the film featured the actors William Dieterle, Otto Gebühr, Olga Tschechowa and Hans Albers.

‘A SANTANOTTE / HOLY NIGHT (Italy, 1922)

35 mm colour print restored by Associazione Orlando (Bologna), Cineteca Nazionale (Rome) and George

Eastman House (Rochester, USA), with the endowment of the Italian Ministry of Culture.

1250 meters, 61 mins (18 fps)

Italian inter-titles

Prod: Films Dora (Neaples), “Serie grandi lavori popolari.”

Director: Elvira Notari

Script: Elvira Notari, based on the song ‘A Santanotte by Eduardo Scala (words), Francesco Buongiovanni

(music).

Photography: Nicola Notari.

Principal cast: Rosè Angione (Nanninella), Alberto Danza (Tore Spina), Eduardo Notari (Gennariello), Elisa

Cava (madre di Tore), Carluccio, a student of Notari’s school of acting.

Original length: mt. 1285.

Based on a popular Neapolitan song by Eduardo Scala and Francesco Buongiovanni, ‘A santanotte was one of the greatest hits of Elvira and Nicola Notari’s Dora Films. It tells the tragic story of Nanninella, a waitress who supports her alcoholic and abusive father Giuseppone. She is in love with Tore, but her father prefers the deceptive Carluccio. When Giuseppone accidentally dies, Carluccio accuses Tore of murder. Nanninella is forced to accept Carluccio’s marriage proposal hoping that this will convince him to withdraw his accusations against Tore. As she tries to escape with Tore on the day of her wedding, the film ends in death and misery. The story has several points in common with that of Assunta Spina, a popular theatrical drama by Salvatore Di Giacomo that Francesca Bertini had adapted into a film in 1915. Yet Notari’s film surpasses its predecessor in its crude representation of patriarchal oppression, offering a powerful melodramatic interpretation of the everyday experience of so many Italian working class women at the beginning of the century.

DIE BÖRSENKÖNIGIN / THE QUEEN OF THE STOCK-EXCHANGE (Germany, 1916)

35mm colour print from the Nederlands Filmmuseum

1090 meters, 52 mins (18fps)

Dutch inter-titles

Prod: Neutral Film

Dir: Edmund Edel

Script: Edmund Edel

Cast: Asta Nielsen, Aruth Wartan, Willy Kaiser-Heyl

Asta Nielsen plays the proprietor of a copper mine on the verge of ruin. After the plant manager has traced a new copper vein, she buys the almost worthless shares and therewith secures the finances of the mine and herself. Gratefully, she makes the manager, with whom she is also in love, a share-holder. But when he deceives her with another woman, she takes revenge with great sovereignty. The film is particularly interesting for its setting – the male-dominated milieus of an industrial plant and of the stock-exchange – and for Nielsen’s superior role in it, which she plays with both style and gusto.

Trailer VADERTJE LANGBEEN / DADDY LONGLEGS (The Netherlands, 1919)

35mm b/w print from the Nederlands Filmmuseum

32 meters, 1 min (18fps)

Dutch inter-titles

Prod: Mary Pickford Co.

Director: Marshall Neilan

Script: Agnes Johnson, based on the novel by Jean Webster

Cast: Mary Pickford (Jerusha Abbott), Milla Davenport (Mrs. Lippett)

Among the few silent trailers of the Filmmuseum collection, this stylish trailer is remarkable for the drawings it contains. Discovered and preserved in 2004 during the international Mary Pickford research project by Christel Schmidt, this film has only been shown in Amsterdam during the Pickford program. Although the trailer shows nothing of the film itself, it constitutes an important evidence to prove the

popularity of Mary Pickford with Dutch audiences.

THE DAWN OF A TOMORROW / NATTENS SKUGGOR (USA, 1915)

35mm colour print from the Archival Film Collections of the Swedish Film Institute

1283 meters, 66 mins (17 fps)

Swedish inter-titles

Prod: Famous Players Film Co.

Director: James Kirkwood

Script: Eve Unsell, based on the novel and the play The Dawn of a Tomorrow by Frances Hodgson Burnett

Principal cast: Mary Pickford (Glad), David Powell (Dandy), Forrest Robinson (Sir Oliver Holt), Robert

Cain (his nephew)

This conference screening will be the premiere of the restored Mary Pickford film The Dawn of a Tomorrow, a film that was considered lost until a tinted nitrate print with Swedish inter-titles surfaced in 2005. The film is set in London and Pickford plays Glad, ”the poorest and happiest of all orphans”. During the course of the film, this angel in a Dickensian world gives shelter to an evicted mother and child, prevents a suicide, intervenes to inhibit domestic violence, and convinces her sweetheart to reform. The beauty of the close-ups displays an extraordinary preciseness of expression that makes this long lost Pickford film a revelation to watch.

FLICKAN I FRACK / THE GIRL IN TAILS (Sweden, 1926)

35mm colour print from the Archival Film Collections of the Swedish Film Institute

2506 meters, 115 mins (19 fps)

Swedish inter-titles

Prod: AB Biografernas Filmdepôt

Director: Karin Swanström

Script: Hjalmar Bergman, Ivar Johansson, based on the novel Flickan i frack by Hjalmar Bergman

Principal cast: Einar Axelsson (Ludwig von Battwhyl), Magda Holm (Katja Kock), Nils Arehn (her father),

Georg Blomstedt (Starck, the headmaster), Karin Swanström (Hyltenius, the vicar’s wife), Erik

Zetterström (Curry, Katja’s brother)

An early example of cross-dressing in Swedish film, a restored version of the comedy Flickan i frack will be screened at the conference for the first time ever. Magda Holm plays Katja, a bright, small-town daughter of an inventor who cares more for the upbringing of his son than his daughter. When Katja’s request for money to buy a new dress for the examination ball is turned down by her father, she decides to attend the ball dressed in tails, creating a further scandal by drinking and smoking cigars. Flickan i frack was Karin Swanström’s fourth and last film as a director, and she also plays one of the leading parts in the film. The film was remade in 1956.

BILLY’S STRATEGEM / DE LIST VAN BILLY (USA, 1912)

35mm b/w print from the Nederlands Filmmuseum, courtesy of the AFI.

290 meters, 14 mins (18fps)

Dutch inter-titles

Prod: Biograph

Director: D.W. Griffith

Script: George Hennessy

Cast: Edna Foster (Billy), Wilfred Lucas, Claire McDowell, Inez Seabury, Robert Harron, William Butler

Billy and his sister are home with their grandfather, while their parents are out working. Their house gets attacked by the Indians, who get past the grandfather. However, Billy has a plan; he finds a way to get out of the house and blows up the house with the Indians in it. This Griffith film, starring Edna Foster as Billy, was repatriated from the Nederlands Filmmuseum archive to the USA, through the AFI, back in 1974. The film was then restored by the AFI, and a projection print, still carrying Dutch titles was kindly donated to the Filmmuseum Collection.

COURAGEOUS COWARD /SUKI’S REHABILITATIE (USA, 1919)

35mm (Desmet method) colour print from the Nederlands Filmmuseum

283 meters, 14 mins (18fps)

Dutch inter-titles

Prod: Haworth Pictures

Director: William Worthington

Script: Frances Guihan, based on a story by Tom Geraghty

Cast: Sessue Hayakawa (Suki Iota), Tsuru Aoki (Rei Oaki)

Suki Iota, a young Japanese-American lawyer, is investigating a murder case and is secretly in love with his custodian’s niece, Rei. When Suki realizes that Rei’s boyfriend Tom is involved in the murder case, he drops it, despite being called a coward for his actions. The only surviving fragment of this long lost film is its last reel. Despite the fact that most of the action is lost, Nederlands Filmmuseum decided to make a presentation print of this fragment, since it is still worthwhile to watch Tsuru Aoki and her real-life husband Sessue Hayakawa in the few romantic scenes that have survived. Another point of interest is the way in which Aoki’s character gets criticized in the film as a young woman of Japanese origins who in her eagerness to become Americanized neglects her own roots.

UMANITÀ / HUMANKIND (1919)

35 mm colour print restored by Associazione Orlando (Bologna) and Cineteca Nazionale (Rome), with

the endowment of the Italian Ministry of Culture.

720 meters, 35 mins (18 fps)

Italian inter-titles

Prod: Liana Film (Rome)

Director: Elvira Giallanella

Script: Based on Vittorio Emanuele Bravetta’s poem Tranquillino dopo la guerra vuol ricreare il mondo

Principal cast: a little boy (Tranquillino), a little girl (Serenetta)

Presented in an introductory title as a “humoristic-satirical-educational” work, the film is centered on two young siblings, Tranquillino and Serenetta, who get up during the night to steal from the jam jar and play with Daddy’s cigarettes. The smoke gives Tranquillino a terrifying dream: the world has been destroyed by a terrible war and his attempts to recreate the world only makes him retrace and redo the mistakes of humankind during the course of history, from dictatorship to war. The backward trip throughout the pastmakes the kids realise that history has been built on arms and war. Desperate and frightened, they seek help in prayer and are finally saved by a bearded God, who appears in the sky and takes them in his arms. Based on a poem for children by Vittorio Emanuele Bravetta, Umanità is the only title in Elvira Giallanella’s filmography as a director. A quite mysterious figure, Giallanella was involved in film production since 1913, when she participated in the founding of the Vera Film company, which produced one of the first Futurist films, Mondo baldoria (1913). It is uncertain whether Umanità was ever screened, as it’s not listed in the censorship archives and never mentioned in period film magazines.

KAERLIGHED OG PENGE / LOVE OR MONEY aka OUTWITTED (Denmark, 1912)

35mm colour print from the Nederlands Filmmuseum

260 meters, 13 mins (18fps)

Dutch inter-titles

Prod: Nordisk Films Kompagni

Director: Leo Tscherning

Script: Harriet Bloch

Cast: Else Frölich, Oscar Stribolt

Kaerlighed og penge is a comedy after a scenario by Harriet Bloch in which men’s intentions with women are getting spoofed. Both the situation and the plot are rather surprising. The main character, Karen, is a well-to-do single mother with a son. She has three admirers courting her: a lieutenant, a poet and a wealthy man. This amuses rather than impresses her, and she candidly questions if they are after her love or her money. One day, her friend from America, Ebba, visits Karin, who seizes the opportunity to throw a party. Together they concoct a test to find out about each man’s true intentions… and they are having a ball while evaluating the outcome.

PAS DE FEMMES! / NO WOMEN! (France, 1920)

35mm (Desmet method) colour print from the Nederlands Filmmuseum

506 meters, 27 mins (18fps)

Dutch inter-titles

Prod: Film Denizot, Marseilles

Director: Vincenzo Denizot

Script: unknown

Cast: unknown

This comedy is exceptional in two respects: first, it seems to be an unknown French production by the Italian director Vicenzo Denizot, known from Maciste-films; and most importantly in the context of this

conference, it seems a rare counterpart to the many anti-suffragette films of the time: it ridicules antifeminism. A luxury hotel by the sea is occupied by a bunch of spoiled girls eager for excitement beyond their daily routines of gourmet dining and playing tennis. The chief rascal among them is Suzy, who preferably drives her governess to despair with her unruliness. One day, a notorious anti-feminist arrives together with his nephew, to recover from the stress of campaigning against furious women. He demands to be served only by men and chases the chamber maid from his room. The girls agree that this is an affront to women’s dignity and Suzy is appointed by lot to scheme and lead their vengeance…

DIE LIST EINER ZIGARETTENMACHERIN / WANDA’S TRICK (Germany, 1918)

35mm colour print from the Nederlands Filmmuseum

920 meters, 45 mins (18fps)

French inter-titles

Prod: Treumann-Larsen Film GmbH

Director: Dr. R. Portegg aka Rosa Porten and Franz Eckstein

Script: Wanda Treumann

Cast: Wanda Treumann, Heinrich Schroth, Marie Grimm-Einödshofer

This is a film produced by and starring German comedienne Wanda Treumann, and co-written and co-directed by Rosa Porten. Rosa Porten made films in the 1910s together with her husband Franz Eckstein, using the pseudonym Dr. R. Portegg. According to contemporary press, they were known for their proficient direction. The film mixes comedy with romance and social drama. It focuses on the interrelations of gender and class and on a factory girl’s independent spirit, business competence, and sense of humour. The plot has a serious undertone, but both its comic twists and Treumann’s guileless acting lend it a striking breeziness and a pro-lib edge.

A remarkable selection, with a palpable sense of exciting discovery. All details of the conference and screenings, including registration, accommodation, location and so forth, can be found on the conference website.