A Spirograph with disc in position, from http://www.westlicht-auction.com

We all know about having motion pictures in disc form. DVD and increasingly Blu-Ray are the domestic formats of choice, and we all understand that films need not appear as strips of film. What is not generally known is that there is nothing new about films in disc form, indeed that films could be found in this form from the earliest years of cinema – indeed the disc form precedes the motion picture film. The recent appearance online (40MB) of a catalogue for the most significant of the film disc formats before DVD – the Spirograph – is the spur for this quick history of the format.

Before there were films there were motion pictures in disc or in circular form. A number of the optical toys and motion picture devices of the nineteenth century involved sequences of images arranged around a disc, with some form of intermittency to enable the viewer to experience the illusion of movement. They included the Phenakistoscope (figures on a disc with slotted edges, effect illustrated here from MOMI), the Zoetrope (sequential images aranged around the inside of a drum with slit holes) and Eadweard Muybridge’s Zoöpraxiscope, which projected images in motion arranged around the edge of a glass disc.

When inventors first began combining the principles of such optical devices with photography, again some looked to discs to provide the solution, particularly if they were reproducing brief sequences (i.e. brief enough to fit within one rotation of the disc. In 1884 John Rudge patented a device which exhibited seven sequential lantern slides of posed photographs (so not motion truly captured by photography) arranged in a circle. The 1887 Tachyscope of Ottomar Anschütz exhibited a disk of twenty-four glass 9×12 cm diapositives turned by a crank. In 1892 Georges Demenÿ took sequential photographic images on celluloid film which were transferred to a glass disc and projected by means of his Phonoscope device (also known as a Bioscope, above). The sequences, of which a man mouthing the words ‘Je vous aime’ is the most famous, were fleeting, but they were motion pictures derived from photographs.

The problem with the use of glass discs was the brevity of the motion sequences. However, before he introduced his successful motion picture system utilising 35mm film strips, Thomas Edison had instructed his engineers to produce a viewing system which arranged celluloid images in micro-form around a cylinder. This wasn’t just being circular for circularity’s sake – the idea was to match motion pictures to devices for the playback of sounds (in this case, Edison’s Phonograph), and early motion picture efforts at creating a disc-based system were clearly driven by a belief that emulating the gramophone disc was the route to creating a successful device for home use.

Kammatograph, from http://www.victorian-cinema.net

It is often forgotten that many of the first motion picture producers saw the domestic market as being their route to riches. This made sense. The Eastman Kodak had put still photography in the hands of anyone; surely the same would occur for motion photography. It was a market that would remain elusive until the introduction (by Eastman) of 16mm film in 1923, but among the various attempts to crack the amateur market were disc-based systems, which offered a simpler, safer option to cameras and projectors using inflammable film.

Among the first and most significant of these was the Kammatograph. Invented in 1898 and marketed from 1900 by Leonard Ulrich Kamm, a Bavarian-born, London-based engineer, the Kammatograph utilised a 12-inch circular glass plate with notched edges caught by gearing with provided the necessary intermittency. There were 350 or 550 sequential images on the disc, arranged in a spiral, giving 30 or 45 seconds running time. It was aimed at the amateur market, and with those lengths of ‘film’ the idea must have been to encourage the filming of portrait shots, akin to snapshots. Not that much is known about the actual use of the Kammatograph, but two of the most prominent users of the device were not ordinary members of the public. William Norman Lascelles Davidson used a Kammatograph for his 1901 experiments on colour cinematography, while Rina Scott (Mrs D.H. Scott) was a botanist who used a customed Kammatograph to make time-lapse films of plant growth.

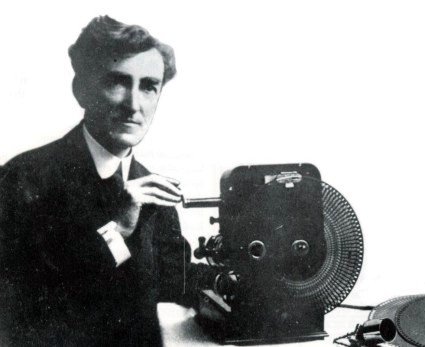

Theodore Brown with his invention, the Spirograph

There were other disc-based systems at this time, often developed as toys for children, among them Cinéphot developed by Clermont-Huet in 1904 and the Animatograph of Alexander Victor in 1909. However the great name is the pre-DVD history of disc-based cinema is the Spirograph. Its history is one of what-might-have-been, and it has of late become an almost cultish subject for those interested in forward-thinking technologies that nevertheless failed to succeed commercially.

The Spirograph was the creation of British inventor Theodore Brown (his wife Bessie was co-patentee) in 1907. It followed the basic idea behind the Kammatograph in presenting motion pictures in the form of miniaturised images arranged on a disc – though Brown’s original idea was to have the images arranged concentrically (he was thinking of very brief sequences and aiming for the toy market), and was tending towards using celluloid rather than glass. However his patent stated that the images could be arranged concentrically or spirally. Brown took the idea to documentary producer Charles Urban, who purchased the patent outright from Brown (supposedly for the hefty sum of $18,000, or £3,600). Urban did not work on the idea immediately, and indeed it was in need of considerable development work before it could be brought to market on the scale that Urban envisaged.

During the First World War, Urban put his engineer Henry Joy onto the task. The images were now arranged in a spiral, the results looking remarkably close to Victor’s earlier Animatograph. The first commercial version was due to appear in the USA in 1917, under the name of the Spiragraph [sic], and then the Homovie. There was no camera planned for sale, only a projector. But a hoped for $1,000,000 flotation of the Urban Spiragraph Corporation was a failure, and further work was held off until after the war.

Spirograph disc and the disc in its sleeve, c.1924, from http://www.spiracollection.com

Urban attempted to re-introduce the re-named Spirograph through his post-war American business Urban Motion Picture Industries, located at Irvington-on-Hudson. The Spirograph in its final form was designed for simplicity of use, being a compact box on a small plinth, operated by a handle, with the exposed disc mounted on the front. The 10½ inch disc was made of safety (i.e. non-flammable) celluloid film, and carried 1,200 frames in a spiral of twelve rows, each frame being 0.22 inches x 0.16 inches. These were miniaturised via a microscopic device from standard 35mm films in the Urban library (using original films between 85 and 100 feet in length, or no more than one-and-a-half minutes long). The Spirograph could project an image four feet wide at a distance of twenty-five feet. It was hand-cranked, with an electrical lamp, and users could halt the disc at any point for illustrative purposes. It was a liberating technology, devised with the teacher in mind – portable, flexible, affordable (the price was to have been $125 per machine and $1.00 per disc), easy to use and useful, except that the films themselves were so short. You can only get so many physical images on a disc. And that probably spelled the Spirograph’s doom

Urban’s intention was to make a huge impact on the burgeoning educational market. While his initial target in 1917 seems to have the home user, now he saw schools, clubs and libraries as his main audience, and he devised imaginative subscription schemes for the hire and return of discs. Urban’s extensive library of non-fiction films stretching back to 1903 would supply the content, thereby finding a new outlet for films that had otherwise ceased to have a commercial value. By the end of 1922 a substantial library of discs was prepared, described in lavish catalogues, with 4,000 Spirographs ready for shipment [update: it is very unlikely that there were actually 4,000 Spirographs made], and a major publicity programme in readiness. But it never happened. Urban’s business overall hit the rocks in 1923 – a simple case of trying to do too much with too little money behind him – and Urban Motion Picture Industries went into receivership in 1924. The Spirograph never made it into the thousands of schools, clubs, halls and homes that Urban dreamt of, and 16mm film (introduced in that fateful year of 1923) gave the target audience a technology that was just as safe and could provide longer films. The Spirograph could be spun no more.

However, that wasn’t quite the end of the Spirograph. The appearance online at the Bibliothèque numérique du cinéma of a 1928 catalogue of Spirograph discs (40MB) shows that the Spirograph did have some sort of commercial life. After the collapse of Urban Motion Picture Industries in 1924 various parts of the Urban empire were picked up by a number of companies, some created for the purpose, among them the Spiro Film Corporation. Little is known about the New York-based company except the obvious source of its name, but clearly it was catering for a market which already had its Spirograph players, since the catalogue makes no mention of how to obtain these, instead restricting itself to listing and describing the 400 discs in the Spirograph collection under such headings as Science, Literature, Government, Physical Activities and Our Government. Theodore Brown himself picked up on residual rights in the Spirograph to market the device in the UK after 1924, but neither he nor Spiro made any success of a technology whose time had passed before it even had a chance to get going.

So the Spirograph Library of Motion Picture Discs (1928) goes into the Bioscope Library’s Catalogues and databases section as part of Catalogue month (which has now crept inexorably into September). The Spirograph is a fascinating technology, not just for its ingenuity but for its potential based around the needs of those outside the commercial exhibition sector. It put the individual user first. Film history, indeed technological history overall, is filled with blind alleys. Looking back on failed systems and collapsing businesses we can see different ways in which things might have gone, and contemplate an alternative cinema history. Instead it took until the 1980s for films to return to disc form for the domestic market (Laser Discs) and the mid-1990s for DVD to gain widespread acceptance among people at large, not because they wanted to be educated but because they wanted to be entertained. And the films were longer.

Finding out more

- Stephen Herbert’s Theodore Brown’s Magic Pictures is a beautifully-illustrated biography of the Spirograph’s multi-talented inventor

- On Charles Urban’s Irvington-on-Hudson venure, including the fateful development of the Spirograph, see my Charles Urban website

- Close-up images of a Spirograph and disc are available on the Spira Collection site (no connection with Spirograph itself – it is the collection of George Spira)

- A illustrated list of glass and disc-based motion picture systems is given on the very useful One Hundred Years of Film Sizes site (though the dates given for the Spirograph are incorrect)

- In 2003 a George Eastman House restoration of a Spirograph disc entitled Man’s Best Friends (i.e. dogs) was presented (on the big screen in 35mm!) at the Pordenone Silent Film Festival (the catalogue date of c.1913 is incorrect – the disc would be c.1921-22)