Recently I was invited to speak at an event taking place Saturday 7 November at the BFI Southbank in London, on women and British silent cinema. There is increasing interest in the role of women in the early years of filmmaking (as demonstrated by Duke University’s Women Film Pioneers project), and as part of this trend the industrious Women and Silent British Cinema project has been investigating all traceable women filmmakers active in Britain in the silent era – including some rather obscure names, for whom little information survives. For my talk I offered to take on a scriptwriter about whom little was known, Mary Murillo, to demonstrate the research process and some of the online sources available. This blog post serves as part of my response.

Mary Murillo does not turn up in any standard motion picture encyclopedia or reference book. Her name is absent from all of the histories of the silent film era that I have consulted (bar a film credit or two), yet she was a significant screenwriter in American film for ten years, then worked in British films for six or more years where her name brought prestige to three different film companies, before she moved to work in French films at the start of the talkies. The fact that she has almost disappeared from film history says a lot about the way in which women filmmakers have been allowed to slip out of early film history, and about the low status of scriptwriters generally. So, how do we go about recovering that history?

Type her name into Google

Type “mary murillo” into Google and you get 15,500 hits. Initially this seems the very opposite of obscurity, but one quickly discovers that the same film credit data has been lifted from one or two sources to be reproduced on numerous filmographic and DVD sales sites, and what is useful information about her is very thin on the ground (one also finds many sites which refer to paintings of the Virgin Mary by the Spanish artist Murillo).

So there’s Wikipedia, which does have a short entry for her – a one-paragraph biography, a filmography and a couple of links. The biography tells us that she was born in Britain, wrote for the Fox, Metro and Stoll studios (the latter in Britain), that most notably she wrote for Theda Bara and Norman Talmadge, and that she was Irish by nationality, though some sources have her as being Latina. This is useful – and correct, because unfortunately the major piece on Mary Murillo available online, ‘Mary Murillo, Early Anglo Latina Scenarist‘ by Antonio Ríos-Bustamante, makes the fatal assumption that her surname meant that she was of Latin American extraction, despite evidence that she was born in Bradford. The writer has uncovered some useful information, but having made a wrong turning at the start, goes off in totally the wrong direction. There are other errors, notably in the filmography, and one is better off with her credits on the Internet Movie Database – over fifty titles – yet one should never accept the IMDb as being accurate or complete, especially for the silent film era, when credits can be difficult to determine (particularly for scriptwriters). Certainly she made more films that are listed there.

Family history sources

For a proper grounding in biographical film research, it is essential to use family history sources. This is where some small investment is necessary, because apart from the volunteer-produced FreeBMD (births, marriages and deaths in the UK, roughly to 1900), the major sources – Ancestry, Findmypast.com etc. – require payment. Ancestry, however, is essential, offering not just births, marriages and deaths, but census records, shipping registers, military records, and much more. The Bioscope has produced a guide to using family history sources in film research, here. Mary Murillo is a problem, however, because it was an assumed name. Her real name was Mary O’Connor. She was of Irish parentage, which is a problem because there are few Irish family history resources online and most pre-1901 census records were destroyed in 1922 during the Civil War. However, Murillo / O’Connor was born in Bradford (explained below) in 1888, yet I can find no official birth record – the first indication of what seems to have been an unconventional childhood.

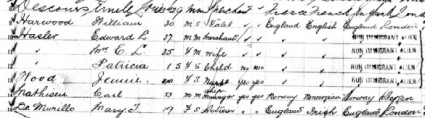

Mary De Murillo, bottom line of this insert from the ship’s register for the S.S. New York, sailing from Southampton 2 August 1909, from http://www.ancestry.com

Shipping records

These are essential. One of the great boons for biographical research recently has been the publication of shipping records, particularly between Britain and the USA before 1960, which give access to passenger registers, or manifests, which contain much biographical information, as well as certain dates. Ancestry has some, Findmypast provides Ancestors on Board using records from The National Archives, but best of all is Ellis Island, a free database with digitised documents of New York passenger records 1892-1924. From Ancestry’s shipping records we discover that Mary first went to American in 1908, under the name Mary de Murillo, where we learn her age (19), that she was Irish but living in England, that she was born in Bradford, that she was an actress, and that she was travelling with her step-sister, Isabel Daintry.

This seems a wonderful clue, though it has proven to be a bit of a dead-end. I’ve not been able to trace a family history for Daintry, who was an actress herself, appearing in a few films in the early 1910s, before fading from history, leaving just a photo (left) from the Billy Rose Theatre Collection in New York Library. One also discovers from the shipping record that Murillo does not give a family member as contact back in England, instead naming a Mrs Henderson of Eton Avenue, London as her friend. One her assumes that her parents were dead. We also learn that she was 5′ 4″ tall, with fair complexion, fair hair and brown eyes, and that she was in good health.

Databases

Why was she travelling to America? Well, she was calling herself an actress, and she was looking for work. Among the several handy databases that one can employ to find biographical information for those in the performing arts, a particularly useful one is the Internet Broadway Database, a free database of production credits for all stage performance’s on New York’s Broadway. And sure enough, there early in 1909 is Mary Murillo appearing alongside Isabel Daintry in the chorus of a musical, Havana. It was not a notable dramatic career – she has three further credits on the IBDB in 1912 and 1913, from which we may infer that she was on tour in stage productions during this period. As newspaper and theatre records reveal, she was a member of Annie Russell’s Old English Comedy Company, performing way down the cast list in plays such as She Stoops to Conquer and The Rivals. This correlates with shipping records, because we find she sailed again from Britain to New York in October 1912, this time on her own, revealed by the manifest for her departure (on Ancestors on Board) and for her arrival (on Ellis Island), with useful the information that her previous stay in the country had lasted for three-and-a-half years.

Census records

Normally census records are the bedrock of biographical research. You get a person’s age, place of birth, family members, occupation, place of residence, and incidental information that one can glean, such as social status. Unfortunately I have not been able to find Mary Murillo/O’Connor on any British or Irish census, though I have found family members (her sisters, but not her parents). However she does turn up in the 1910 New York census, where she is a lodger in Manhattan, given as born in England, profession stage actress, no other family member with her. Something to be wary of – the electronic versions of such data, in this case Ancestry, are based on transcriptions and often the names have been written down wrong – for the 1910 census, Ancestry has her name as Mary Minter. Later census records have not yet been made publicly available.

Newspapers

At some point in 1913 or 14, Mary Murillo sold a film scenario to the husband-and-wife production team of Phillips Smalley and Lois Weber. Her career as an actress had not taken off, and like many others before her she looked to the movie industry as a way out, though in her case it was through her pen. She clearly had talent, because within two years she was one of the leading film scenarists in the American film business, becoming chief scriptwriter at Fox in 1915. This rise to fame one can trace through the best source for any online research of this kind, the newspaper archives. There are so many of these, though few are free, so either you pay a subscription or you hope your local library subscribes. Major resources include Newspaper Archives.com (for American papers), the Times Digital Archive and Guardian Archive. Free resources include Australian Newspapers, New Zealand’s Papers Past and a private archive of American papers, Old Fulton NY Post Cards. Film publicity departments sent out supporting bumf worldwide, and you can find Mary Murillo’s name scattered all over the place, becase such was her prominence that her name was frequently mentioned as a leading feature – in ‘reviews’, advertisments and posters. The Bioscope has produced a guide to newspaper archives online, though it’s in need of some updating.

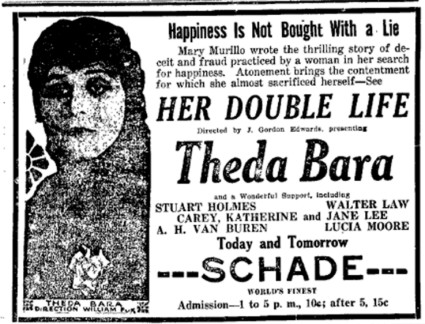

Advertisment for Her Double Life, from the Sandusky Star Journal, 28 September 1916, available from Newspaper Archives.com

Mary Murillo specialised in exotic melodrama, and wrote five scripts for Theda Bara, Hollywood’s archetypal vamp. The films were Gold and the Woman, The Eternal Sapho, East Lynne, Her Double Life and The Vixen. From an article in the New York Clipper, 1 May 1918 (found at Old Fulton’s NY Post Cards), entitled ‘The Scenario Writer’, we learn this:

Even as late as the year 1914, there were few companies who deemed the writer worthy of mention on the screen and as for proper financial reward, many an excellent five reeler brought the magnificent sum of seventy-five dollars. Slowly but surely, however, the big film producers have come to realize the importance of the scenario writer in the general scheme of things with the result that from being one of the most poorly paid individuals connected with the industry, the men and women who create the successful screen plays today, now receive monetary recompense of substantial proportions. Mary Murillo, for example, a scenario writer, who made over twenty-five thousand dollars last year, sold her first script for twenty-five dollars, four years ago. She is but one of many scenario authors, who unsung and ignored but a few years back, are now reaping similar big rewards in the scenario field.

Quite a leap from stage obscurity to $25K a year in just four years. Newspaper records also tell us that Murillo left Fox at the end of 1917 to go independent, working for Metro amongst others, before joining the staff of Norma Talmadge productions in 1919, where she scripted such titles as Her Only Way, The Forbidden City and The Heart of Wetona, plus others such as Smilin’ Through where her name does not turn upon official credits but where she seems to have been a script doctor – a role she performed many times, making her exact filmography a difficult subject on which to be precise.

She ended her American film career in 1922. Why this was one can only speculate. Perhaps she wanted new challenges, perhaps her penchant for high-flown romanticism was starting to be out of fashion, or perhaps it was related to a revealing report in the New York Times of 18 March 1923, where we learn of the seizure by a deputy sheriff of a five-storey at 338 West Eighty-Fifth Street leased by Miss Mary Murillo, “a scenario writer, now said to be in Hollywood”. She had defaulted on her payments. Among the goods seized were “tapestries alleged to be valuable, a mahogany grand piano, phonograph and a quantity of records, a lot of silver and a leopard skin”. Mary had been living the movie life, and how.

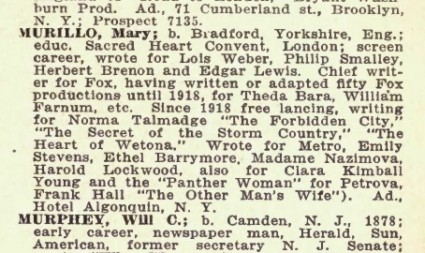

Contemporary movie guides

It’s worth remembering that there were reference guides produced from the early 1910s onwards that provide biographical information on those before and behind the camera in the film business. Often the personal information provided needs to be taken with a pinch of salt, but it’s always a handy starting point. Some of these are available on the Internet Archive: for example, Charles Donald Fox and Milton Silver’s Who’s Who on the Screen (1920), and the 1921 edition of William Allen Johnston’s Motion Picture Studio Directory and Trade Annual. The latter has an entry on Mary Murillo, which seems to be wholly accurate, as follows:

Motion Picture Studio Directory and Trade Annual 1921

Trade papers

There is plenty one can find about Mary Murillo from American newspaper sources, even if mostly of a superficial kind. Once she moved to Britain, the online sources dry up, because she gets little mention in the digitised British newspapers. She started writing for Stoll Film Productions, the major British studio of the early 1920s, resulting in five films: The White Slippers (1924), The Sins Ye Do (1924) and A Woman Redeemed (1927), plus two (possibly three) titles for other studios. Information on these is best found in film trade papers, such as the Bioscope and the Kinematograph Weekly, which do not exist online and need to be located at the BFI National Library, British Library Newspapers (which has produced a useful list of British and Irish cinema and film periodicals that it holds), or on microfilm sets at film research centres. There are no indexes to such resources – you just have to scroll through them and hope to strike lucky, though the BFI’s onsite database provides many references (these are missing from the online version of the database). One trade journal that does have a handy index is the American Moving Picture World, and it is from Annette M. D’Agostino’s invaluable Filmmakers in the Moving Picture World: An Index of Articles, 1907-27 that I found an article on Murillo from 16 March 1918 – though only after looking twice, because her name was indexed as Murrillo (remember never to trust indexes implicitly – always look laterally, and be prepared for mispellings etc). From that I got the photograph at the top of this post and some tantalising biographical information, including her schooling at a convent in Roehampton, near London. (By the way, the American journal Variety does publish indexes, for film titles and an obituaries index, only in printed form).

Ask people

Of course, asking people is a hugely important part of research. It’s always best to do a bit of research yourself rather than expect others to do all your work for you, but armed with some information you’ve been able to gather, turn to the experts. Having taken my research so far, I posted a query on the classic film forum Nitrateville, which is jam-packed full of knowledgeable people only too willing to help. It so happened that none knew anything about Mary Murillo directly, but one or two respondees came up with excellent leads. One used Google Books, which enables you to search through snippets of texts from books old and current and found a mention of her in a Belgian memoir – more of that below. Another looked in the Irish Times Digital Archive, a subscription site, and found that there seemed to be an article on her in 1980. I have access to the site at work (see here for a list of all full-text, word-searchable newspapers and journals available electronically at the British Library), and discovered that the article was a piece by Irish film historian Liam O’Leary on the director Herbert Brenon, with whom Murillo worked. O’Leary, as an aside, revealed the precious information that her real name was Mary O’Connor, and that she came from Tipperary.

Tipperary and Bradford? Something odd there, but the Liam O’Leary papers are held in the National Library of Ireland, where former cameraman and known walking encyclopedia of Irish film history, Robert Monks, has care of the papers. Bob looked up Liam’s card index for me and found reference to an article on her in the October 1917 issue of Irish Limelight, a short-lived film trade journal. Happily, the British Library has Irish Limelight. From this I learned that her family came from Ballybroughie – though there’s a problem there, as there is no such place as Ballybroughie, at least as far as I can find. Her early years were spent near Tipperary, though as she and her sisters (more of them in a minute) were born in Bradford the family clearly moved around a bit. She mentions her father (no name) but not her mother, boasts of her great muscial gifts when young, says that she chose the name Murillo because she was compared when young to a Murillo madonna painting, and describes how tough she found it finding work as an actress.

She also mentions the convents she went to – St Monica’s in Skipton, Yorkshire, and Convent of the Sacred Heart School in Roehampton. This is now Woldingham School and the archivist there told me that Mary O’Connor (born 22 January 1888) and her sisters Philomena and Margaret were at Roehampton for a year (1903-04) before deciding that its tough regime was not for them. The parents’ (parent?) address is given as Thomas Cook c/o Ludgate. He, or they, were overseas (the travel agents Thomas Cook’s main offices were in Ludgate Circus, London). In the 1901 census Philomena, Margaret and another sister Winifred (but not Mary) are given as boarding at St Monica’s, aged respectively 4, 3 and 7. What were the first two doing in a boarding school at that age? Were the absent parents touring performers, or involved in international (Empire?) business, or just plain neglectful?

Mary Murillo turns up in a couple of British newspapers in the late 1920s when her name was used by two film companies issuing prospectuses in the hope of investment. In The Times, 29 November 1927, the British Lion Corporation (with backing from the author Edgar Wallace) announced that its grand plans included “a contract with Miss Mary Murillo, whereby she is to write two complete Film scenarios for the Company during the year 1928”. It also makes the surprise claim that she wrote the script for The Magician by Rex Ingram (Irish himself, of course), something not otherwise recorded in any source. She also turns up in the prospectus the Blattner Picture Corporation (found in The Daily Mirror 21 May 1928, available from pay site ukpressonline) where it declares that “the company will from its inception will have expert technical assistance, and in particular Miss Mary Murillo (formerly Scenarist for the Metro-Goldwyn Corporation, Messrs Famous-Players Lasky, Mr D.W. Griffith, Miss Norma Talmadge &c.) will write Scenarios for this Company’s first year’s programme”.

This is useful, though only a couple of films seem to have come out of her association with British Lion, and none with Blattner. She made some films in France, apparently working on English versions of French releases, though she is credited for the script of the 1930 classic Accusée, levez-vous!. Her last film credit is as a co-writer of the British film, My Old Dutch, in 1934. Then what? Well, the Belgian source I mentioned was Les Méconnus de Londres (2006), the memoirs of Tinou Dutry-Soinne, widow of the Secretary to the Belgian Parliamentary Office in London, which cared for Belgian exiles during World War II. She met Mary Murillo in London at that time, and provides a sketch of a lively, interesting character with a fascinating history in film behind her who was keen to help Belgian exiles. An email to the obliging people at the Belgian embassy in London got me Mme Dutry’s address, and she wrote me a most friendly and detailed letter with all the information she could find on her social contacts with Mary Murillo up 10 October 1941, the last time she saw her. Murillo wanted to do what she could to help the Belgian cause (she seems to have spent some time in Belgium before the war), but suddenly disappeared from the scene.

Archives

And then what? I don’t know. She just vanishes. She appears not to have married nor to have had children. I have found no death record, though admittedly Mary O’Connor is not an easy name to research. But for the film researcher the biographical information, though a necessary backbone, is not the main business. She was a scriptwriter, and we want to find film her surviving scripts, and surviving films. Firstly we need reliable film credits. I’ve said that IMDb is a good start, but always double-check with at least two other sources. The filmography at the end of this post comes from a combination of the IMDb, references in newspapers, the Library of Congress Catalog of Copyright Entries: Motion Pictures 1912-1939 (available in PDF form from the Internet Archive), the American Film Institute Catalog (for which the records for silent films are accessible to all), Denis Gifford’s British Film Catalogue 1895-1985 and the BFI database. There are some uncertain titles in the filmography – as said, she seems to have tidied up others’ scripts at times, or to have developed scripts which were then completed by other hands, so determining what is her work outright is not easy.

There is no register of all extant film scripts, and one has to search in multiple places. I found two Murillo shooting scripts in the indexes of the BFI National Library in London (The Sins Ye Do, A Woman Redeemed). The Margaret Herrick Library of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences has a Motion Picture Scripts Database, from which I found nine scripts, held by UCLA and AMPAS itself: Ambition, The Bitter Truth, The Little Gypsy, Love’s Law, The New York Peacock, A Parisian Romance, Sister against Sister, Two Little Imps and The Vixen (the poster, right, for her 1917 film Tangled Lives, comes from the Margaret Herrick Library site). Some of these scripts are also held in the Twentieth Century-Fox archives, as Antonio Ríos-Bustamante discovered. WorldCat, the union catalogue of world libraries, lists two scripts available on the microfilm set What women wrote: scenarios, 1912-1929. All in all, a remarkable fourteen Murillo scripts survive, a gratifyingly high number.

Finding what films exist in archives (as opposed to the DVD store – I think only two of Murillo’s films are available this way – The Forbidden City, from Grapevine and Accusée levez vous! from Pathé – but Silent Films on DVD is the place to check) is not easy. Again, no central register exists, and not all film archives publish catalogues of their holdings, let alone online catalogues. A list of world film archives is provided by the Federation of International Film Archives. A useful first source for checking whether a film survives and where (chiefly American titles, though) is the Silent Era website, which continues on its way to becoming the single-stop essential source for information on silent films. Otherwise, you just to check a lot of catalogues and ask in a lot of places (once again specialist fora such as Nitrateville or the Association of Motion Picture Archivists (AMIA) discussion list are home to many experts, archivists and collectors). The filmography at the end of this post lists the dozen Murillo films known to survive.

Round-up, and a few tips

This post documents some of the avenues down which I’ve travelled trying to uncover information on one obscure film scriptwriter from the silent era. It’s not a typical research enquiry, but then what such enquiry ever is? It should show that you start out with some basic sources and some key questions to ask, but then will find yourself led down all sorts of unexpected avenues, because people are unexpected.

And why research someone so obscure? You have to ask? Is there any nobler activity out there than to recover a life? Certainly it is always excellent when anyone recovers a corner of history that has been lost or ignored, however small it may seem. It’s a contribution to knowledge, and telling us something that we didn’t know before is a whole lot better way to spend your time as a researcher than re-telling that which we already know. So go out and do likewise – and then tell the world about it. Meanwhile, I’ve much more to try and find out somehow about Mary Murillo. What was her connection with D.W. Griffith? What films did she write for Nazimova? Who were her parents? Do any other photographs of her exist? When did she die? The quest goes on.

A few tips. Never trust any source on its own – always verify the information in two or three other places. Remember that people tell lies about themselves. Official documents such as birth certiifcates, census forms and shipping registers tell us much, but they can also mislead (sometimes deliberately – people lie about ages etc.) and the electronic databases suffer from mistranscriptions. Always think laterally. Remember when searching for female subjects that names change on marriage, and of course with Mary Murillo we have someone who lived under an assumed name. Don’t expect to find everything online, and don’t expect to find everything immediately, and be prepared to spend a little money for valuable resources that have taken a lot of money and effort to compile. Use the Bioscope Library for standard reference sources of the period, its FAQs page for tips on searching, and the categorised links on the right-hand column as a guide to the online world of silent film.

And have fun.

Filmography

This post is long enough as it is, so the Mary Murillo filmography can be downloaded here as a PDF of an Excel file. It includes script and print sources.

In incredible story or research and dogged determination. Fabulous post!

I’m wondering I’ve become so obsessive about this story, but thank you anyway.

None of us passengers on this bus are obsessive. Nope, not us. Nosireebob.

Brilliant detective work!

Thanks for telling us so much more about this intriguing woman. It’s a fascinating research trail… (NM)

It should be stressed that this is just a starting point. I’ve tried to demonstrate for anyone keen to undertake a similar journey that there is so much that can be found through online sources (a major theme for the Bioscope). However, so much more can only be discovered by trawls through the archives and by patiently scouring the trade papers. As it is, I now have the birth registration details of one of her sisters, so I can order a birth certificate and get the names of the parents, at last. So I’ll keep on the case, but I need also to move on to other women filmmakers for the Women and British Silent Cinema project and the planned Women Film Pioneers Sourcebook. Next stop, Jessica Borthwick…

I’ve written a biographical sketch of Mary Murillo, with sources and filmography, for the Women and British Silent Cinema site:

More information continues to emerge on Mary Murillo. In the mid-1930s she was heavily involved in the motion picture colour process Francita, known in the UK as Opticolor or Realita.

I have discovered much more information on Mary Murillo since writing this original post. Chiefly I have found that her partner was French cinematographer Maurice Velle, son of French early film pioneer Gaston Velle. This has led to many new avenues of enquiry. The story is brought up to date in this blog post on my personal site: http://lukemckernan.com/2015/05/16/gaston-maurice-and-mary/