News in 2011, clockwise from top left: The White Shadow, The Artist, A Trip to the Moon in colour, Brides of Sulu

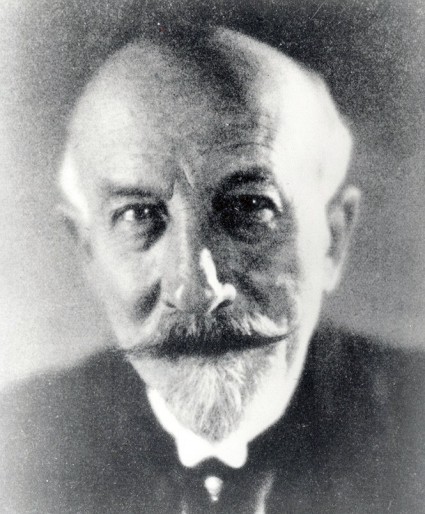

And so we come to the end of another year, and for the Bioscope it is time to look back on another year reporting on the world of early and silent film. Over the twelve months we have written some 180 posts posts, or well nigh 100,000 words, documenting a year that has been as eventful a one for silent films as we can remember, chiefly due to the timeless 150-year-old Georges Méliès and to the popular discovery of the modern silent film thanks to The Artist. So let’s look back on 2011.

Ben Kingsley as Georges Méliès in Hugo

Georges Méliès has been the man of the year. Things kicked off in May with the premiere at Cannes of the coloured version of Le voyage dans la lune / A Trip to the Moon (1902), marvellously, indeed miraculously restored by Lobster Films. The film has been given five star publicity treatment, with an excellent promotional book, a new score by French band Air which has upset some but pleased us when we saw it at Pordenone, a documentary The Extraordinary Voyage, and the use of clips from the film in Hugo, released in November. For, yes, the other big event in Méliès’ 150th year was Martin Scorsese’s 3D version of Brian Selznick’s children’s novel The Invention of Hugo Cabret, in which Méliès is a leading character. Ben Kingsley bring the man convincingly to life, and the film thrillingly recreates the Méliès studio as it pleads for us all to understand our film history. The Bioscope thought the rest of the film was pretty dire, to be honest, though in this it seems to be in a minority. But just because a film pleads the cause of film doesn’t make it a good film …

And there was more from Georges, with his great-great-grandaughter Pauline Duclaud-Lacoste Méliès producing an official website, Matthew Solomon’s edited volume Fantastic Voyages of the Cinematic Imagination: Georges Méliès’s Trip to the Moon (with DVD extra), a conference that took place in July, and a three-disc DVD set from Studio Canal.

For the Bioscope itself things have been eventful. In January we thought a bit about changing the site radically, then thought better of this. There was our move to New Bioscope Towers in May, the addition of a Bioscope Vimeo channel for videos we embed from that excellent site, and the recent introduction of our daily news service courtesy of Scoop It! We kicked off the year with a post on the centenary of the ever-topical Siege of Sidney Street, an important event in newsreel history, and ended it with another major news event now largely forgotten, the Delhi Durbar. Anarchists win out over imperialists is the verdict of history.

Asta Nielsen in Hamlet

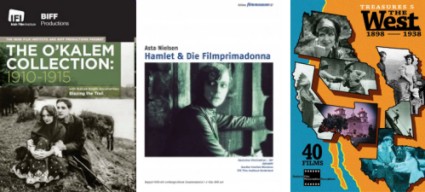

We were blessed with a number of great DVD and Blu-Ray releases, with multi-DVD and boxed sets being very much in favour. Among those that caught the eye and emptied the wallet were Edition Filmmuseum’s Max Davidson Comedies, the same company’s collection of early film and magic lantern slide sets Screening the Poor and the National Film Preservation Foundation’s five disc set Treasures 5: The West, 1898-1938. Individual release of the year was Edition Filmmuseum’s Hamlet (Germany 1920), with Asta Nielsen and a fine new music score (Flicker Alley’s Norwegian surprise Laila just loses out because theatre organ scores cause us deep pain).

We recently produced a round-up of the best silent film publications of 2011, including such titles as Bryony Dixon’s 100 Silent Films, Andrew Shail’s Reading the Cinematograph: The Cinema in British Short Fiction 1896-1912 and John Bengston’s Silent Visions: Discovering Early Hollywood and New York Through the Films of Harold Lloyd. But we should note also Susan Orlean’s cultural history Rin Tin Tin: The Life and the Legend, which has made quite an impact in the USA, though we’ve not read it ourselves as yet.

There were all the usual festivals, with Bologna championing Conrad Veidt, Boris Barnet and Alice Guy, and Pordenone giving us Soviets, Soviet Georgians, polar explorers and Michael Curtiz. We produced our traditional detailed diaries for each of the eight days of the festival. But it was particularly pleasing to see new ventures turning up, including the Hippodrome Festival of Silent Cinema in Scotland, which launched in February and is due back in 2012. Babylon Kino in Berlin continued to make programming waves with its complete Chaplin retropective in July. Sadly, the hardy annual Slapsticon was cancelled this year – we hope it returns in a healthy state next year.

The Artist (yet again)

2011 was the year when the modern silent film hit the headlines, the The Artist enchanting all-comers at Cannes and now being touted for the Academy Award best picture. We have lost count of the number of articles written recently about a revival of interest in silent films, and their superiority in so many respects to the films of today. Jaded eyes are looking back to a (supposedly) gentler age, it seems. We’ve not seen it yet, so judgement is reserved for the time being. Here, we’ve long championed the modern silent, though our March post on Mr Bean was one of the least-read that we’ve penned in some while.

Among the year’s conferences on silent film themes there was the First International Berkeley Conference on Silent Cinema held in February; the Construction of News in Early Cinema in Girona in March, which we attended and from which we first experimented with live blogging; the opportunistically themed The Second Birth of Cinema: A Centenary Conference held in Newcastle, UK in July; and Importing Asta Nielsen: Cinema-Going and the Making of the Star System in the Early 1910s, held in Frankfurt in September.

In the blogging world, sadly we said goodbye to Christopher Snowden’s The Silent Movie Blog in February – a reminder that we bloggers are mostly doing this for love, but time and its many demands do sometimes call us away to do other things. However, we said hello to John Bengston’s very welcome Silent Locations, on the real locations behind the great silent comedies. Interesting new websites inclued Roland-François Lack’s visually stunning and intellectually intriguing The Cine-Tourist, and the Turconi Project, a collection of digitised frames for early silents collected by the Swiss priest Joseph Joye.

The Bioscope always has a keen eye for new online research resources, and this was a year when portals that bring together several databases started to dominate the landscape. The single institution is no longer in a position to pronounce itself to be the repository of all knowledge; in the digital age we are seeing supra-institutional models emerging. Those we commented on included the Canadiana Discovery Portal, the UK research services Connected Histories and JISC Media Hub, UK film’s archives’ Search Your Film Archives, and the directory of world archives ArchiveGrid. We made a special feature of the European Film Gateway, from whose launch event we blogged live and (hopefully) in lively fashion.

Images of Tacita Dean’s artwork ‘Film’ at Tate Modern

We also speculated here and there on the future of film archives in this digital age, particularly when we attended the Screening the Future event in Hilversum in March, and then the UK Screen Heritage Strategy, whose various outputs were announced in September. We mused upon media and history when we attended the Iamhist conference in Copenhagen (it’s been a jet-setting year), philosophizing on the role of historians in making history in another bout of live blogging (something we hope to pursue further in 2012). 2011 was the year when everyone wrote their obituaries for celluloid. The Bioscope sat on the fence when considering the issue in November, on the occasion of Tacita Dean’s installation ‘Film’ at Tate Modern – but its face was looking out towards digital.

Significant web video sources launched this year included the idiosyncractic YouTube channel of Huntley Film Archives, the Swedish Filmarkivet.se, the Thanhouser film company’s Vimeo channel, and George Eastman House’s online cinematheque; while we delighted in some of the ingenious one-second videos produced for a Montblanc watches competition in November.

It was a year when digitised film journals made a huge leap forward, from occasional sighting to major player in the online film research world, with the official launch of the Media History Digital Library. Its outputs led to Bioscope reports on film industry year books, seven years of Film Daily (1922-1929) and the MHDL itself. “This is the new research library” we said, and we think we’re right. Another important new online resource was the Swiss journal Kinema, for the period 1913-1919.

It has also been a year in which 3D encroached itself upon the silent film world. The aforementioned Hugo somewhat alarmingly gives us not only Méliès films in 3D, but those of the Lumière brothers, and film of First World War soldiers (colourised to boot). The clock-face sequence from Harold Lloyd’s Safety Last (also featured in Hugo) was converted to 3D and colourised, much to some people’s disgust; while news in November that Chaplin’s films were to be converted into 3D for a documentary alarmed and intrigued in equal measure.

The Soldier’s Courtship

Film discovery of the year? The one that grabbed all the headlines – though many of them were misleading ones – was The White Shadow (1923), three reels of which turned up in New Zealand. Normally an incomplete British silent directed by Graham Cutts wouldn’t set too many pulses running, but it was assistant director Alfred Hitchcock who attracted all the attention. Too many journalists and bloggers put the story ahead of the history, though one does understand why. But for us the year’s top discovery was Robert Paul’s The Soldier’s Courtship (1896), the first British fiction film made for projection, which was uncovered in Rome and unveiled in Pordenone. It may be just a minute long, but it is a perky delight, with a great history behind its production and restoration.

Another discovery was not of a lost film but rather a buried one. Philippine archivists found that an obscure mid-1930s American B-feature, Brides of Sulu, was in all probability made out of one, if not two, otherwise lost Philippines silents, Princess Tarhata and The Moro Pirate. No Philippine silent fiction film was known have survived before now, which makes this a particularly happy discovery, shown at Manila’s International Silent film Festival in August. The Bioscope post and its comments unravel the mystery.

Among the year’s film restorations, those that caught the eye were those that were most keenly promoted using online media. They included The First Born (UK 1928), Ernst Lubistch’s Das Weib des Pharao (Germany 1922) and the Pola Negri star vehicle Mania (Germany 1918).

Some interesting news items throughout the year included the discovery of unique (?) film of the Ballet Russes in the British Pathé archive in February; in April Google added a ‘1911’ button to YouTube to let users ‘age’ their videos by 100 years (a joke that backfired somewhat) then in the same month gave us a faux Chaplin film as its logo for the day; in May the much-hyped film discovery Zepped (a 1916 animation with some Chaplin outtakes) was put up for auction in hope of a six-figure sum, which to few people’s surprise it signally failed to achieve; and in July there was the discovery of a large collection of generic silent film scores in Birmingham Library.

Barbara Kent

And we said goodbye to some people. The main person we lost from the silent era itself was Barbara Kent, star of Flesh and the Devil and Lonesome, who made it to 103. Others whose parting we noted were the scholar Miriam Hansen; social critic and author of the novel Flicker Theodore Roszak; the founder of Project Gutenberg, Michael Hart; and the essayist and cinéaste Gilbert Adair.

Finally, there were those ruminative or informational Bioscope posts which we found it interesting to compile over the year. They include a survey of cricket and silent film; thoughts on colour and early cinema; a survey of digitised newspaper collections, an investigation into the little-known history of the cinema-novel, the simple but so inventive Phonotrope animations of Jim Le Fevre and others, thoughts on the not-so-new notion of 48 frames per second, the amateur productions of Dorothea Mitchell, the first aviation films, on silent films shown silently, and on videos of the brain activity of those who have been watching films.

As always, we continue to range widely in our themes and interests, seeing silent cinema not just for its own sake but as a means to look out upon the world in general. “A view of life or survey of life” is how the dictionary defines the word ‘bioscope’ in its original use. We aim to continue doing so in 2012.