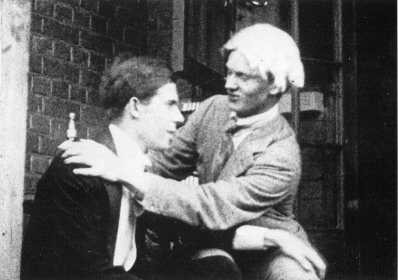

Fritz Rasp as the spy Schmale © Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung; Bildbearbeitung: Dennis Neuschäfer-Rube

A day on from all the excitement of the news that a print of the previously ‘lost’, complete Metropolis had been found in Argentina, the dust has settled a little, and more information has filtered through. So here’s a round-up of the film’s history, the discovery of the print, and why the news is so significant.

Let us travel to the year 2026, not so far away now. The giant city of Metropolis is maintained by a slave army which runs the machines which served the pampered ruling class. Freder, son of the city’s ruler, is captivated by a beautiful woman, Maria, and in following her discovers the horrors of the underground life of Metropolis. Maria is a figurehead for the restless workers, and Freder’s father instructs the scientist Rotwang to build a robot in her image so that the workers will follow ‘her’ and be duped into avoiding revolution. But the robot goes beserk and incites a rebellion. Eventually the workers see how they have been misled. They destroy the robot, while Freder, his father and Maria are reunited in happiness, Capital and Labour united at last. So, your typical tale of twenty-first century life.

Such was the vision conjured up by German film director Fritz Lang and his scenarist wife Thea von Harbou for the 1927 film Metropolis, one of the most ambitious, expensive (for the German film industry) and iconic of all silent films. However, at the time it was something of a flop with audiences. The industry reponded as the industry will, and cut the film drastically, to the extent of losing scenes essential to the film’s dramatic logic. Some 950 metres were removed; almost a quarter of its original length. The film at its original length of 4189 metres (147 mins at 25fps, though there is argument over the correct running speed) was therefore only seen for a short while (until May 1927 in Berlin); thereafter a cut version of around 113 mins was all that could be seen, and – so far as posterity aware – all that had survived thereafter, despite various restored versions being produced, most recently that overseen by Enno Patalas in 2001 (which runs at 118 mins).

Move forward to 2008. Paula Félix-Didier, newly installed as curator of the Museo del Cine in Buenos Aires, learns from her ex-huband (director of the film department at the Museum of Latin American Art) of a curiously long screening of a print of Metropolis at a cinema club some years before, a print which was now believed to be in the Museo del Cine. According to ZEITmagazin, which has reconstructed the story, one Adolfo Z. Wilson, who in 1928 ran the Terra film distribution company of Buenos Aires, had secured a copy of the full length version of Metropolis for screening in Argentina. A copy then found its way into the hands of film critic Manuel Peña Rodríguez. In the 1960s he sold the film to Argentina’s National Art Fund, with seemingly neither party to the deal realising the unique value of the film. A print (on 16mm) then came into the hands of the Museo del Cine in 1992. Sixteen years later, Paula Félix-Didier found it.

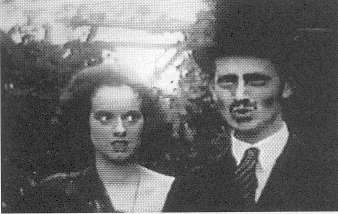

Maria (Brigitte Helm) flees from the mob © Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung; Bildbearbeitung: Dennis Neuschäfer-Rube

Félix-Didier then acted with care. Rather than announce the discovery in Argentina (where, apparently, she believed it would not attract so much attention) she chose to have the discovery announced in Germany, where the film had been produced, and where the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung had been responsible for the most recent restored version of the film. She also had a friend who was a journalist for ZEITmagazin, which is how it ended up getting the exclusive and the stills which reveal that the print is indeed a well-worn 16mm copy, but whose very murkiness and lack of sharpness seem only to add to their haunting quality. (Word is that the stills are frame grabs from a DVD copy, so they look a little worse than the print actually is)

So, what is it that we have? What was found was a 16mm dupe neg of virtually the entire original version of Metropolis, minus just one scene, that of a monk in a cathedral, because it happened to be at the end of a reel that was badly torn (this information from Martin Koerber of the Deutsche Kinemathek, via the AMIA-L discussion list). The original 35mm nitrate print is lost. Precise details of the missing scenes (which were cut by the film’s American distributors, Paramount) are unclear, but it is reported that they reveal why the real Maria is mistaken by a rampaging mob for the robot created in her image; the significance of the role of the spy Schmale (played by Fritz Rasp), who pursues Freder, is made clear; and the scene where the workers’ children are saved by Freder and Maria towards the end of the film is revealed to be far more dramatic, and violent (a likely reason for its having been cut in the first place).

From Ain’t it Cool News, showing the trapped workers’ children trying to escape flood waters

And what will happen now? The above-mentioned restored version was produced in 2001, and has been made available on DVD in deluxe editions by Kino and Eureka. There is also a study or critical edition available from the Filminstitut der Universität der Künste Berlin. Kino recently announced that it would be issuing Metropolis on high-definition Blu-Ray early in 2009 – how will the news affect their plans?. The Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung has announced its intention to produce a ‘restored’ version, which would presumably simply mean inserting the relevant ‘lost’ sequences into the existing 35mm restoration. The reports from those who have seen the rediscovered print all indicate how coherent the complete work is, and hence how logically the extra scenes would slot in. Of course, there would be a somewhat brutal shift from pristine 35mm to battle-worn 16mm, but other such attempts at full restorations have shown similar changes in image quality where only inferior material remains, and the effect is not so jarring. Far more important will be the realisation of a story – and of one of the twentieth-century’s masterpieces of art in any form – made whole again. But what will get released, in what form, and when – it’s too soon to say.

© Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung; Bildbearbeitung: Dennis Neuschäfer-Rube

Where to find out more:

- David Hudson’s GreenCine Daily has plenty of background information on the film’s discovery, with updates from what’s being published in Die Zeit

- Kino, as well as having details of its DVD release, has QuickTime clips of the 2001 restored version.

- Kino also has a flashy (it uses Flash) special site on the film and its restoration, which has everything bar clips

- Extensive information on the film and its DVD versions is available on the Celtoslavica site

- There are reports on the discovery of the Argentinian print in ZEITmagazin (original report with images and follow-up report), Reuters, The Guardian and Variety

- There are more images from the 16mm print on Ain’t it Cool News

- A glossy history of the film is given in Zeit Online – in German, but with gorgeous images

- The best place online for information on German films of the 1920s is the very fine www.filmportal.de site (in English and German)

- Lastly, check yesterday’s post on this site, which has the text of a press release from the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung, with yet more information

One last thought. What other lost silents might be lurking in South American film archives, perhaps not as thoroughly investigated as their North American cousins, but a territory where many American prints will inevitably have turned up? After such a tremendous discovery, we can only be greedy for more.

Update (4 July): Today in Argentina journalists were shown extracts from the rediscovered print of Metropolis. Photographs show that they were shown a DVD with brief clips. Reports indicate that the clips they were shown were (i) a worker who has exchanged clothes with Frederer gets in a car and drives to Yoshiwara, Metropolis’ red-light district; (ii) Smale, the spy following Frederer, at a newspaper stand; (iii) the robot Maria is seen in Yoshiwara; (iv) Frederer and the real Maria rescue the workers’ children, including scenes where the children are seen trapped behind bars as the flood water rise.

According to Digital Bits, Kino are intending to include the rediscovered new sequences in their already-announced Blu-Ray release of Metropolis from early next year, though it is surely too early for such confident pronouncements.

Further update (12 February 2010): For a report on the restored film’s premieres and the latest news news, see https://bioscopic.wordpress.com/2010/02/12/the-new-metropolis/.