The Bioscope is off to the Giornate del cinema muto (the Pordenone silent film festival) for the next week. A full Pordenone Diary will be published on my return.

The passion of Joan of Arc

In the Nursery is a Sheffield-based group which has made a speciality of soundtracks to silent films, including The Cabinet of Caligari, Asphalt, Man with a Movie Camera, Hindle Wakes, A Page of Madness and the Mitchell & Kenyon compilation Electric Edwardians. Its latest production is Carl Th. Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc, which they have been touring since April. A CD of the soundtrack has just been released, which, we are ressued, “reflects the film’s dramatic highs and lows – from the emotional close-up photography of the trial through to the fevered final scenes surrounding Joan’s death”. More information on the In the Nursery site, which has ample information on recordings and shows, with an MP3 download section.

There’s no such thing as a bad home movie

Frame still of Mavis and Margaret Passmore (holding a piece of 35mm film), from the Passmore family films, c.1903, held by the BFI National Archive

So says John Waters, and while we’ve probably all sat through some relative’s earnest document of their holiday abroad and wished that some of the panning shots of scenery could have been a little shorter, he has a point. Home movies aren’t to be judged by the usual film rules. They are made for an interior purpose; every frame speaks to a select family audience which alone can decode the film’s particular references. And yet, as time passes, and such films turn up in archives, they then speak in a different way to us all, as we see the manners, the customs, the backgrounds, the clothing, the choice of subjects, that make these films such rich social historical documents. Moreover, in other people’s home lives, we see our own. In all these respects, there can be no such thing as a bad home movie.

Image from a Kinora portrait record of the polar explorer Ernest Shackleton and his son Edward, c. 1912, from http://www.jates.co.uk

Home movies are as old as cinema. They were produced throughout what was the silent era in commercial cinema, and continued to be shot silent for several decades thereafter. Some have argued for the scenes of their family life filmed by the Lumière brothers in 1895-96 to be the first home movies, but these were studied compositions for commercial consumption. However, cameras and projectors were soon aimed at the amateur market – indeed, in those first years of cinema some believed that the real money would be made by targeting the home. After all, the Kodak camera had shown where the business lay for still photography. Probably the first motion picture device for amateur use was the Birtac, a camera-printer-projector utilising 17.5mm film, introduced by Birt Acres (hence the name) in 1898. The Biokam, developed by Alfred Darling and Alfred Wrench followed in 1899. Gaumont in France came up with the Chrono de Poche, using 15mm film, in 1900. The Lumières themselves were behind the Kinora, a hand-held, flick-card viewer for which you could either have films made of your family as a ‘portrait’ in a studio, or film them yourself with camera using paper negatives (it was patented in 1896 but the first Kinora camera for amateur use appeared in 1907).

See a QuickTime movie of a Kinora in action, from the Royal Collection

Other such systems followed, employing narrow gauges which were cheaper and easier to handle. Initially the film used was flammable nitrate, but in 1912 there came the Edison Home Kinetoscope using 22mm safety film, and in the same year the Pathéscope, or Pathé Kok, using 28mm safety film. However, these were mostly for showing commercial films in the home, and it was 9.5mm film (introduced 1922) that was the format taken up most avidly by amateurs seeking to shoot their own films, though 16mm (introduced 1923) was used by the wealthy, and some of the first home movies in archives are those shot by the well-to-do upper middle class in the 1920s. A rival to 9.5mm that would soon overtake it in popularity was 8mm, introduced in 1932, and Super 8 appeared in 1965.

Thomas Edison with his Home Kinetoscope, introduced 1912, from Adventures in Cybersound

35mm was rarely used for home movies, such was the expense (and the fire hazard), but some examples exist, including what I think must be the earliest surviving home movies, those of the Passmore family of Streatham, filmed 1902-1908 and held in the BFI National Archive. They are a delight (they were shown at the Pordenone silent film festival in 1995). Home movies have grown in importance for film archives, or rather film archives have grown up which value such productions highly because of the way they record people and place. The smaller, or regional film archives around the world, are preserving a picture of our private selves which is likely to be rather more highly valued by future generations than the progressively quaint commercial entertainment films that still dominate moving image archiving philosophy generally.

All of which leads us to Home Movie Day. This is an international event, now in its sixth year, and for 2008 it falls on 18 October. Home Movie Day celebrates amateur film and amateur filmmaking through a wide number of events held locally at venues across the world. The events provide ordinary people with the opportunity to see home movies, show their home movies to others, to discover about home movie heritage, and to learn how best to care for such films. This year there are events taking place in Argentina, Australia, Canada, Germany, Italy, Japan, Mexico, the Netherlands, Slovenia, the United Kingdom, and at many points across the USA. The Home Movie Day site provides information on all the events and the home movie day ethos. In the UK, there will be events in Manchester and London. This is the blurb for the London event:

On Saturday October 18, archivists and film lovers around the world will take time out of the vaults to help the public learn about, enjoy, and rescue films forgotten with the advent of home video. Home Movie Day shows how home movies on 8mm, Super8 and 16mm film offer a unique view of decades past, and are an essential part of personal, community, and cultural history.

Home Movie Day returns to London this year at the Curzon Soho cinema bar. It’s a free event and open to everyone. There will be a Film Clinic, offering free film examinations by volunteer film archivists from the British Film Institute, Wellcome Library and BBC, who will check the film for any damage and deterioration, and offer advice about how to store film in the home.

After examination, the films can be passed to one of the projectionists, who will be continuously screening home movies throughout the day.

You don’t need to bring a film to attend and enjoy the event; everyone has a chance to win prizes generously donated by the BFI and Wellcome Collectionjust by viewing any of the films on the day. Prizes include BFI DVDs and tickets to the IMAX.

The archivists can also offer advice about preserving films in film archives around the UK and transferring films to other formats such as DVD so they’remore easily watchable in the home.

Don’t throw your films away; bring them to Home Movie Day!

The London event takes place at 12-5pm at the Curzon Soho, 99 Shaftesbury Avenue, London W1D 5DY. For more information, contact Lucy Smee, at Dearoldsmee [at] gmail.com. The Manchester event takes place at the North West Film Archive.

The history of amateur film remains underwritten, though work has been done of late to remedy this. You could start with by Karen L. Ishizuka and Patricia R. Zimmermann’s Mining the Home Movie: Excavations in Histories and Memories (2007), or seek out Zimmermann’s earlier Reel Families: A Social History of Amateur Film (1995). There’s also Alan Kattelle’s Home Movies, A History of the American Industry, 1897-1979 (2000).

For the cameras and projectors designed for amateur use in the ‘silent’ era, the best source is Brian Coe’s The History of Movie Photography (1981), while the Kinora is covered by Barry Anthony in The Kinora – motion pictures for the home, 1896-1914 (1996). For images and information on narrow gauge film formats from the early period, visit the excellent (if increasingly out of date so far as its name is concerned) One Hundred Years of Film Sizes.

To find out about the work of regional film archives in the UK, visit the Film Archive Forum website. Film Forever is a good online guide to the preservation of films at home. Our history is in your hands.

Bioscope centenary

I cannot let September 2008 pass without noting a modest centenary, which is that of the original Bioscope. On 18 September 1908 The Bioscope, the British film trade journal was first published, having its roots in two earlier magazines, The Amusement World and The Novelty News. It continued as a weekly until 4 May 1932. For most of that period it was published by Ganes Ltd, and edited by John Cabourn. It took its name from what was then a common term for the new venues for exhibiting motion pictures (i.e. cinemas), but which was also known as a type of film projector and a term for fairground film shows. It was a redolent and versatile term, describing both its subject it the widest terms and its own view on the world.

The Bioscope reported on British and world film production and exhibition, reporting the latest news and studio gossip, reviewing films, reporting on technology, interviewing leading figures in the industry, and keeping a sharp eye on the business side of film. For the film historian, it is one of the key primary sources for the study of silent film – certainly in Britain, and with much of great value for film from other nations as well. It was a major source for Rachael Low’s The History of the British Film series, and has been cited in countless studies since, not least on account of the British Film Institute’s library having a complete run.

In recognition of this Bioscope’s honourable forebear, I am going to start up a new series, at least once a month reproducing texts from The Bioscope of 100 years ago. Whether this Bioscope will last another twenty-four years seems unlikely (how long will blogs last?), but we’ll trace how The Bioscope reported on the rise of the cinema business from 1908 for as long as it does.

Professor Pepper at the Polytechnic

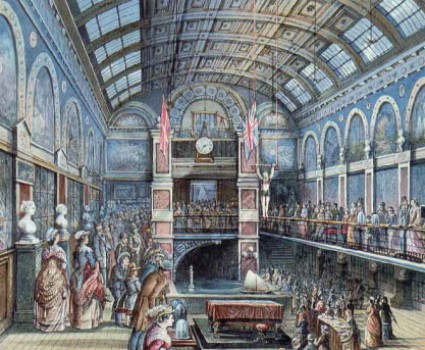

Interior of the Great Hall at the Royal Polytechnic, from http://www.magiclantern.org.uk

The Magic Lantern Society and the University of Westminster have organised a series of talk and events to be held at the University of Westminster’s central London site at 309 Regent Street, which was formerly the Royal Polytechnic Institution. For much of the nineteenth century the Polytechnic was London’s leading centre for the popularisation of science, hosting lectures, lantern shows, scientific demonstrations, and – on 20 February 1896 – the debut of the Cinématographe Lumière in Britain.

Visual technologies and performance were a stape attraction of the Polytechnic, and it is in this spirit that the series is being presented, under the name of one of the most popular of contemporary stage illusions, Pepper’s Ghost. This invention of ‘Professor’ John Henry Pepper, a director of the Polytechnic, this simple but ingenious illusions whereby ghostly figures could appear on stage was the subject of an earlier post, after its unexpected use in a Paul McCartney pop video.

As the blurb for the series puts it, the one hour talks and events

celebrate the spirit of the old Polytechnic featuring rarely-seen London-based historical material, physical demonstrations of “lost media” and surprisingly new applications of ancient optical techniques by contemporary visual artists, stage performers, filmmakers and designers.

‘Professor Pepper’s Ghost: Six Evenings of Optical Magic at the Old Polytechnic‘ got underway on 23 September, so apologies for being late with the news, but here’s the full line-up:

Tuesday 23 September

The World’s First Projection Theatre

Jeremy Brooker provides a guide (both virtual and actual) to the Royal Polytechnic’s famous optical theatre.Tuesday 7 October

3D or Seeing Double

Dr David G. Burder offers a ‘sensational’ guide to the art and history of seeing things in 3-dimensions.Tuesday 21 October

The Diorama: Weaving Time and Space

Photographer and video artist Simon Warner looks at the work of Daguerre and the Diorama phenomenon in the 1820s and 30s.Tuesday 4 November

The Charing Cross Whale and the Fleas of Regent Street

Professor Vanessa Toulmin presents an illustrated and astonishing look at the wide range of ephemeral entertainments which captured the public imagination of visitors to London in the 19th century, drawing on rarely-seen flyers and bill material in the National Fairground Archive.Tuesday 18 November

Old Media: New Light

Freelance illustrator Geoff Coupland showcases his own work and that of his students from the Camberwell College of Art applying what are often referred to as 19th century and earlier ‘dead media’ forms such as the magic lantern, shadow-play and flickbooks, to illustrate modern ideas and points of view.Tuesday 2 December

The Magic Lantern Believe it or Not

In this unruly entertainment ‘Professor’ Mervyn Heard highlights some of the more bizarre, surprising and often horrifying lantern ‘entertainments’ of the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries and attempts to prove that, in the right hands, ‘the lantern lecture’ could be much more than a naive precursor to cinema: instead the basis for inspired live performance.

The prize goes to Professor Vanessa for the catchiest title, but all sound enticing. All the lectures start at 7pm, and admission is free, with tickets issued from 6pm. For further information, visit the University of Westminster site.

Projection Box Awards

Phenakistiscope, from Stephen Herbert’s not-MOMI site

A reminder to you all that entries are welcomed for the 2008-09 Projection Box Essay Awards. Established last year by the UK independent small publisher, The Projection Box, the awards are for essays on a theme relating to historical, artistic or technical aspects of popular optical media. The subject of this year’s competition is Popular Optical Media (to 1900), including nineteenth century photography, Dioramas, Zoetropes, the magic lantern, shadow theatre, panoramas, Victorian cinema, and optical toys.

First prize is £250 and publication in the journal Early Popular Visual Culture (Routledge). Plus book prizes. Last year’s first prize went to Dr John Plunkett for his essay ‘Selling Stereoscopy 1890-1914: penny arcades, automatic machines and American salesmen.’

Submissions are invited for unpublished essays of between 5,000 and 8,000 words. Entry is open to all, and the deadline for entries is 24 January 2009. Full details, including competition rules, are available on the Projection Box Awards site.

(You’ll find not-MOMI (a recreation of parts of the defunct Museum of the Moving Image) at http://easyweb.easynet.co.uk/~s-herbert/momiwelcome.htm.)

Bioscope Newsreel no. 7

Bardelys on TV

Bardelys the Magnificent (1926), the recently-discovered King Vidor feature starring John Gilbert, will get its television premiere on France 3 on 12 October, as part of the Cinéma de Minuit strand. The film will also be appearing the same week on the big screen for the first time in eight decades at the Pordenone Silent Film Festival. Read more.

Conference call

The 30th Annual Meeting of the Southwest/Texas Popular and American Culture Association takes place 24-28 February 2009 at Hyatt Regency, Albuquerque, New Mexico. The meeting covers many aspects of cinema, and the Area Chair for Silent Film is seeking papers and presentations on any aspect of Silent Film. Suggested topics include D.W. Griffith’s art, Garbo, Modern Silent Films and Filmmakers, Bronco Billy and the Rise of the Western, Studios and companies during the silent age, The birth of Talkies, Al Jolson, Lillian Gish, Silent Documentaries, Silent Horror films, Hitchcock’s silent movies, Edison, Birth of Science Fiction and the Fantasy Film, Edwin Porter. Abstracts and titles should be sent by 15 November to Rob Weiner (Rweiner5 [at] sbcglobal.net). Read more.

Quasimodo rocks

Vox Lumiere, the enterprising troupe that puts on rock musical versions of silent film classics, is bringing its intepretation of Lon Chaney’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame to DPTV-Detroit Public TV in the USA. The production is scheduled to air in December as part of the PBS National Pledge Drive. Read more.

Memories of Lloyd

The Ghent Film Festival, which runs 7-18 October, is including a retrospective of Harold Lloyd comedies, under its ‘Memory of Film’ section. The films featured are Movie Crazy, Safety Last, Speedy, and the sound film Welcome Danger. Read more.

‘Til next time!

The Bioscope Guide to … Italy

Lyda Borelli (left) and Francesca Bertini, drawn by Tito Corbella

Time to start up another series, and this time it’s going to be an occasional series looking at the history of silent cinema in various countries, with a list of resources (offline and online) to aid the researcher. One can argue against the need for national histories of cinema, even that such nationalism creates myopic and self-serving accounts, but their value (and popularity) probably outweigh such qualms – and they do provide us, quite literally, with boundaries. And so we start with Italy.

History

Italy’s contribution to silent cinema was a considerable and a distinctive one, but it was slow off the mark. Although it had some pioneer experimenters in the 1890s, such as Fileteo Alberini, for the most part film in the first years meant exhibition of films from other nations or actuality filmmakers such as Vittorio Calcina (who was a Lumière representative) and Italo Pacchioni, perhaps the first independent native filmmaker. At this period, when films were widely exhibited in Italy but local production was minimal, the leading figure was probably Leopoldo Fregoli, an immensely popular comedian and mimic who introduced film (the Fregoligraph) into his act in 1898.

Italian film production properly began in 1905 with the production by Alberini and fellow exhibitor Dante Santoni of La Presa di Roma (The Capture of Rome), Italy’s first dramatic film, prophetic in its choice of classical-historical subject matter. A year later their company took on the name of Cines. The growth in cinemas, and a great upsurge in audiences, encouraged an explosion in native film production. Among the leading companies were Cines, Ambrosio, Pasquali, Itala, Comerio (later Milano) and the Pathé offshot Film d’Arte Italiana. The leading production centres were Rome and Turin, and Italian films were exported worldwide as well as locally, establishing a strong reputation for costume dramas and comedies. Italy became one of the world’s leading film production centres.

Italian filmmakers (and audiences) delighted in classical and literary subjects, tackling Shakespeare, Dante and Edward Bulwer-Lytton (the much-filmed The Last Days of Pompeii), films which delighted in emphasising opulence, elevated drama and a classical heritage that was especially theirs. This taste for the cultured came in part from the aristocratic leanings, indeed blood, of some Italian producers and investors, men like actor and director Gustavo Serena, Alberto Fassini (who owned Cines), Giuseppe Di Liguoro, who ran Milano Films and was the company’s main director, and Baldassare Negroni, another aristocrat-filmmaker, this time for Celio.

To demonstrate that their cinema was not all high-minded, Italian comedians developed a rudely cinematic, knockabout style that blended chase, social satire and film trickery, with such notable comics as Cretinetti (the Frenchman André Deed), Kri Kri (Raymond Frau), Lea (Lea Giunchi) and Tontolini (Ferdinando Guillaume) and Robinet (Marcel Fabre). Delightfully Italian in their particular vaudeville style, such films also point the way to the American slapstick that was eventually to supplant them on the world market.

Cabiria (1914), from http://www.bfi.org.uk/features/cinemaitalia

As films grew longer, Italian ambitions grew. The taste for classical subjects led inexorably to grander treatments – the literal cast of thousands – as films started to dazzle audiences with scale and spectacle. Out of the major Italian studios came a succession of epic, feature-length productions that caused amazement worldwide: L’Inferno (1911), which shocked many with its scenes of writhing nudity, La caduta di Troia (The Fall of Troy) (1911), Quo vadis? (1913), Cajus Julius Caesar (1914) and grandest and maddest of them all, Giovanni Pastrone’s Cabiria (1914). Cabiria, a tale of the Punic Wars, was 4,000 metres long (over three hours) and came burdened with grossly verbose titles courtesy of Italy’s great poet/dramatist Gabriele D’Annunzio. Cabiria‘s commanding sense of space (accentuated by distinctive slow camera tracking shots), visual design, and the movement of crowds impressed all who saw it, even while the human drama was dwarfed. It particularly influenced the epic film in America, most noticeably D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance. Cabiria also introduced the character Maciste, the Hercules-like strongman, played by Bartolomeo Pagano, who would feature as the leading character in a great many films throughout the 1910s and 20s, and then revived as a character in the 1960s.

Cinema fascinated Italian intellectuals. Futurism, the modernist art movement that largely centred on Italy, theorised rhapsodically about film and its relation to the urban and the mechanical. Futurists Arnaldo Ginna and Bruno Corra made experimental films in 1910-1912 which combined motion picture colour with music, and Ginna made the film Vita futurista (1916). Conversely, Luigi Pirandello’s wrote a novel Si gira (1915), revised in 1925 as Quaderni di Serafino Gubbio operatore (English title Shoot!), in which cinema is representative of all that is mechanised and soulless.

The epic productions made Italy the talking point in world cinema for a brief period, but another national form of film – and one more localised in its appeal – was the diva film. These were slow moving but artfully designed melodramas, with scenarios where strong leading ladies suffered glamorously, usually dying for love in the final reel. Italian diva actresses included Pina Menichelli (Tigre Reale, 1916), Francesca Bertini (Assunta Spina, 1915, which she co-directed), Lyda Borelli (Malombra, 1917), Maria Jacobini (Resurrezione, 1917) and Italia Almirante Manzini (L’inamorata, 1920), while their celebrated stage equivalent was Eleonora Duse (who made just the one film, Cenere, in 1916).

Post-war, Italian cinema withered away. The dominance achieved by America worldwide, and the competition in Europe from German cinema, had a deleterious effect on the Italian film industry, which could no longer afford to produce the lavish films of which its reputation had been based. Production dwindled almost to nothing by the mid-1920s, and quality declined in tandem (with some brave exceptions, such as Maciste all’Inferno, 1926). Fascism, dominant in Italian life from 1922, showed little interest in film until sound arrived in 1930, and with it a revival in Italian cinema – but that is another story.

Notable filmmakers

Arturo Ambrosio, Mario Caserini, Giuesppe De Liguoro, Enrico Guazzoni, Gerolamo Lo Savio, Luigi Maggi, Baldassare Negroni, Elvira Notari, Roberto Omegna, Ernesto Maria Pasquali, Giovanni Pastrone, Eleutrerio Rodolfi

Notable performers

Franceca Bertini, Lyda Borelli, Leopoldo Fregoli, Emilio Ghione, Lea Giunchi, Ferdinando Guillaume, Leda Gys, Maria Jacobini, Italia Almirante Manzini, Pina Menichelli, Amleto Novelli, Bartolomeo Pagano, Ruggero Ruggeri

DVDs

These are Italian silents currently on DVD (more will be added here as I find them):

- Assunta Spina (d. Francesca Bertini, Gustavo Serena 1915) [Kino]

- Cabiria (d. Giovanni Pastrone 1914) [Kino]

- Christus (d. Giuseppe Di Liguoro 1914) [Grapevine]

- Diva Dolorosa [Zeitgeist]

Peter Delpeut’s ‘found footage’ documentary on Italian silent melodrama, using fourteen films including La donna nuda (1914) and Tigre reale (1916) - Gli ultimi giorni di Pompei (d. Mario Caserini 1913) [Kino]

- Maciste all’inferno (d. Guido Brignone 1926) [Grapevine]

- Marcantonio e Cleopatra (d. Enrico Guazzoni 1913) [Grapevine]

- Salammbo (d. Dominico Gaido 1914) [Grapevine]

- Silent Shakespeare [BFI] [Milestone]

Includes Re Lear (d. Gerolamo Lo Savio 1910) and Il mercante di Venezia (d. Gerolamo Lo Savio 1910)

Publications

The finest publications on silent Italian cinema are, inevitably, in Italian. This is a selection of some of the leading titles, with a smattering of English language texts. Current academic interest tends to lie with the leading actresses of the teens and women directors such as Elvira Notari and Elvira Giallanella.

- Aldo Bernardini, Cinema muto italiano vols. 1-3 (1980-1982)

- Aldo Bernardini, Cinema muto italiano: I film “dal vero”, 1895-1914 (2002)

- Ivo Blom, ‘Italy’, in Richard Abel (ed.), Encyclopedia of Early Cinema (2005)

- Giuliana Bruno, Streetwalking on a Ruined Map: Cultural Theory and the City Films of Elvira Notari

- Angela Dalle Vacche, Diva: Defiance and Passion in Early Italian Cinema (2008) [The book is accompanied by Peter Delpeut’s DVD Diva Dolorosa]

- Jean A. Gili, André Deed (2005) [in Italian]

- Vittorio Martinelli, Le dive del silenzio (2001)

- Geoffrey Nowell-Smith, The Companion to Italian Cinema (1996)

- Renzo Renzi, Sperduto del buio: Il cinema muto italiano e il suo tempo (1905-1930) (1991)

- Pierre Sorlin, Italian National Cinema 1896-1996 (1996)

Luigi Pirandello’s novel Si gira (1915), or Shoot! is available for free from Project Gutenberg (Australian version)

Journals

The following silent film era journals from the Museo Nazionale del Cinema are availablein digitised form from the Teca Digitale piemontese:

- Bollettino di informazioni cinematografiche – 1924-1925

- Bollettino edizioni Pittaluga – 1928-1929

- Bollettino staffetta dell’ufficio stampa della anonima pittaluga – 1929-1931

- Cine Mondo: rivista quindicinale illustrata de cinema – 1927-1931

- Al cinema: settimanale di cinematografia e varietà – 1922-1930

- Eco film: periodico quindicinale cinematografico – 1913

- Figure mute: rivista cinematografica – 1919

- Films Pittaluga: rivista di notizie cinematografiche: pubblicazione quindicinale – 1923-1925

- Il Maggese cinematografico: periodico quindicinale – 1913-1915

- Rassegna delle programmazioni – 1925-1926

Archives and museums

Italy has a couple of outstanding film/pre-cinema museums, and a profusion of film archives with silent film holdings to one degree or another.

- l’Archivio audiovisivo del movimento operaio e democratico

- La cineteca del Friuli

- Cineteca di Bologna

- Cineteca nazionale

- Fondazione cineteca Italiana

- Museo del precinema (Minici Zotti collection)

- Museo nazionale del cinema

- Museu del cinema (Girona)

Festivals

Italy is the home of film festivals, and boasts three that specialise in silent film, two of them exclusively. Pordenone and Bologna (which includes sound films) share honours for being the world’s leading festivals of early film.

- Il cinema ritrovato (Bologna)

- Giornate del cinema muto (Pordenone)

- Strade del cinema (Aosta)

Websites

- 100 Years of Cinema Exhibition in Italy

Part of a site on the history of cinema-going in Italy – includes basic information on cinemas and exhibition in the silent era - Archivio Storico

Thousands of newsreels and documentaries from 1928 onwards produced by Luce (and others), with many video clips - CinemaItalia

General history of Italian cinema written by David Parkinson, with a section on the silent era - Divina Lyda

Biographical site (in Italian) on Lyda Borelli, with many photographs - Dive cinema muto

Italian site (in Italian) devoted especially to the Italian ‘divas’ such as Lyda Borelli and Francesca Bertini (site no longer active – link is to Internet Archive record) - In penombra

Valuable new site on aspects of Italian silent film history, in Italian but with English translation software - Non solo dive

This site for a 2007 conference on women and Italian silent cinema seems no longer to be active, but conference details are on a Bioscope post - Unsung Divas of the Silent Screen

Mostly American actresses, but pages on Bertini, Borelli and Menichelli, with useful links

Quebec and Québec

F. Guy Bradford (left), Joe Rosenthal (right) and the Living Canada travelling company, c.1903 (Cinémathèque québécoise)

Another day, another site goes up with unique silent film content, richly contextualised. Truly the online world is our archive. This time it is Le cinéma au Québec au temps du muet/Cinema in Quebec in Silent Era, an impeccably bilingual site giving us the history of early cinema in Quebec, Canada.

Quebec has a distinctive early film history. It is a tale coloured by its geography, its French heritage, local regulations, audiences and enthusiasms, and by snow. Particularly, it is a tale shaped by the dedicated efforts of a hardy band of pioneers, such as James Freer, Henry de Grandsaignes d’Hauterives and Léo-Ernest Ouimet. It is a tale of travelling cameramen (Joe Rosenthal, William Paley) and travelling exhibitors (F. Guy Bradford), an adventurous cinema with a spirit of newness and discovery about it.

The site has been put together with impressive thoroughness and local pride. There are extensive, knowledgable texts on such themes as the history of cinema in the area, biographies, audiences, film companies, sponsorship (the Canadian Pacific Railway made much use of film to promote its activites), censorship and travelling cinema. There are twenty or so films, available in low and high bandwidth, mostly non-fiction, including such titles as Skiing at Quebec (Edison 1902), Mes espérances en 1908 (Ouimet 1908), The Building of a Transcontinental Railway in Canada (Butcher 1909), Put Yourself in their Place (Vitagraph 1912 – fiction film set in Quebec) and the sobering Forty Thousand Feet of Rejected Film Destroyed by Ontario Censor Board (James and Sons 1916). All have musical accompaniment by Canada’s own Gabriel Thibaudeau.

There are also three lively ‘interactive journeys’ which you can take through the ‘Rural Milieu (1897-1905)’, ‘Working-Class Milieu (1906-1914)’ and ‘Middle-Class Milieu (1915-1930)’, which is an interesting way in which to divide up cinema history. Plus you will find documents, photographs, further background texts (some in French, some in English, some in both), and educational activities and a good, eclectic set of links (where you may learn that The Bioscope is ‘Plus qu’un blogue’ – merci beaucoup). An historical timeline is also offered, though I’ve not been able to make the link work. All in all, an exceptional piece of work, lovingly constructed, with discoveries a-plenty to be made.

The site is a collaborative effort between GRAFICS, the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec and the Cinémathèque québécoise. Acknowledgments to Bruce Calvert on the indispensible silent film forum Nitrateville for information on this site.

Immersed in the past

Visitors viewing the Gettysburg Cyclorama, from http://www.washingtonpost.com

A step back from the silent film to one of its antecedents. On 26 September the Battle of Gettysburg cyclorama opens to the public at the new Gettysburg visitor centre after a five-year, $15 million restoration, contained within its own rotunda. The cyclorama is a 337ft x 42ft panoramic painting of the Battle of Gettysburg, painted by Frenchman Paul Philippoteaux (with twenty assistants) and first exhibited in 1884.

The painting (which weighs some three tons) is a 360-degree oil painting depicting “Pickett’s Charge,” a Confederate attack that took place on 3 July 1863. It was commissioned as a commercial venture by Chicago businessman Charles Louis Willoughby. Philippoteaux, an experience panoramic painter, began work in 1882, making hundreds of sketches of the Gettyburg battlefield and hiring a photographer to produce panoramic photographs of the site. He interviewed veterans to help him with the details, then spent eighteen months producing the painting, hiring assistants to work on specialised features such as horses, soldiers and landscape. The finished work was not just the panoramic painting but included three-dimensional features coming out of the painting, such as trees, walls and fences, which, when added to the tricks in perspective employed by the panorama painters, gave viewers a greater sense of the physical ‘reality’ of the experience. The 3-D aspects are recreated in the restored version.

The panorama was a patented invention, created by the Irishman Robert Barker in 1787. Giant panoramic paintings, known as cycloramas in their 360-degree form, became hugely popular visitor attractions throughout the nineteenth century, inviting audiences to lose themselves in historical scenes, Biblical scenes and exotic journeys, generally with a lecturer to guide them to the highlights to be seen along the way. The form therefore anticipated much of the spectacular and immersive qualities of cinema, and is seen as one of the ‘pre-cinema’ antecedents of motion picture films. Both are imaginatively constructed journeys through time and space.

View a QuickTime panorama of the top half of the pre-restored painting.

The Battle of Gettysburg was so successful following its Chicago debut that Philippoteaux produced a second version for exhibition in Boston, then two further copies (surely painting at its most mechanical and soulless). It is the Boston version, which later moved to the Gettysburg National Military Park, which has been restored. One other copy survives.

There are some thirty or so cycloramas in existence today, in one form or other. Information on these, with links to those with a web presence of some kind, can be found on the Visions & Illusions site. The International Panorama Council’s Panoramapainting.com describes and illustrates panoramas of all kinds to be found worldwide.

There is information on the restoration of the cyclorama from the National Park Service site. The Washington Post reviews the restoration with a somewhat jaundiced eye, looking at its propagandist qualities and its relationship to virtual reality, echoing the need for realistic thrills in modern museum installations. The report also has a short video on the Gettysburg panorama.