http://www.cinemateca.gov.br/jornada

Last year we noted for the first time the remarkable festival of silent film in Brazil, the Jornada Brasiliera de Cinema Silencioso or Brazilian Journey of Silent Cinema. The festival returns again 6-15 August and has a strong enough programme to make you think seriously about chaning your holiday plans. The festival is organised by the Cinemateca Brasiliera, São Paulo and is curated by Carlos Roberto de Souza. As the festival press release puts it:

This annual event is dedicated to world cinema produced between the late nineteenth century until about 1930, when the arrival of sound changed the course of the cinematic art. Now in its 4th edition, the Journey has become an important part of the Brazilian cultural calendar, and allows an increasingly larger and more diversified audience to gain access to films from the silent cinema era.

All of the Festival’s scheduled features are to be accompanied by live musical performances in the Cinemateca-BNDES Theater, with ‘silent projections’ (I guess that means silent only) in the Cinemateca-Petrobras Theater.

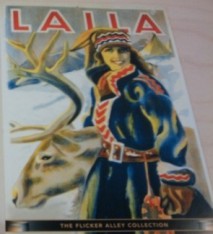

As in previous festivals, a special feature is made of the production of a national cinema of the silent period and the work of a particular country’s film archive. This year the focus is Swedish silent cinema, and the selected works are restorations from the Swedish Film Archive (Svenska Filminstitutet / Kinemateket). Altogether, there are thirty-five titles, curated into six programmes.

The Nordic countries developed a film industry whose films spread all over the world, until the outbreak of World War I. Although after the war European production had ceded its economic importance to Hollywood movies, Sweden had one of the most brilliant cinemas in film history, with directors like Victor Sjöström and Mauritz Stiller producing great works of artistic expression, not to mention exceptional actors like Lars Hanson and Greta Garbo. The Jornada presents a selection of works that will show a wider panorama of Swedish silent cinema and the film restoration work which has been developed in that country for decades. The opening event will present the film The Blizzard / Gunnar Hedes Saga (Mauritz Stiller, 1923), with live musical performance from Dino Vicente. Alongside the great works of Sjöström and Stiller, to be shown in recent restorations, the festival will present the first film record made in Sweden (Konungens af Siam landstigning vid Logårdstrappan / Arrival of the King of Siam in Logårdstrappan, 1897), and the celebrated Häxan (Benjamin Christensen, 1922), in a print considered by the archive’s curator as the most beautiful of the entire collection.

The Jornada’s inaugural lecture will be given by Jon Wengström, curator of the Swedish Film Institute’s Archival Film Collections; its main themes will be Swedish silent cinema and the conservation work carried out in Sweden. He will speak about the criteria that guided his selection of Swedish Film Treasures, which include two films starring Greta Garbo – Die freudlose Gasse / The Joyless Street (G.W. Pabst, Germany, 1925) and Flesh and the Devil (Clarence Brown, USA, 1926), as well as the single existing fragment of the actress’s collaboration with Sjöström, The Divine Woman (USA, 1928), the scandalous Afgrunden / The Woman Always Pays (Urban Gad, Denmark, 1910), and the extraordinary The Wind (USA, 1928), directed by Sjöström and starring Lillian Gish, which will be presented in the version with musical soundtrack that was released at the time.

The Wind

Other highlights are the films The Dawn of a Tomorrow (James Kirkwood, USA, 1915), starring Mary Pickford, and the audacious Tretya Meshchanskaya / 3 Meshchanskaya Street, or Bed and Sofa (Abram Room, USSR, 1927).

The Jornada has a section which features highlights from Pordenone’s Giornate del Cinema Muto. This year Paolo Cherchi Usai has selected some American productions, the oldest one being the surprising Regeneration (1915), directed by Raoul Walsh; When the Clouds Roll By (1919), directed by Victor Fleming and starring Douglas Fairbanks and Stage Struck (Allan Dwan, 1925), with Gloria Swanson.

Another regular feature is silent films from Brazil. This year the festival will show some documentary feature films restored by the Cinemateca Brasileira in recent years, such as Companhia Paulista de Estrada de Ferro and Companhia Mogyana, portraying industrial labour and the building of the main railways in different cities of the São Paulo region. In the feature drama O Segredo do corcunda (Alberto Traversa, 1924) the train has an important dramatic function, to connect the State’s capital, from the magnificent Estação da Luz, to a small town, with its modest little train station. Turibio Santos, legendary guitarist and the director for many years of the Villa-Lobos Museum, will perform with this film as a special guest of the festival.

The programme “Window to Latin America” will show Wara Wara, made in Bolivia in 1929 by José María Velasco Maidana, which depicts an episode of the Inca civilization during the Spanish invasion. One of the few surviving Bolivian silent films, it was restored at the laboratory L’Immagine Ritrovata in Bologna, Italy, and has been presented at the festival Il Cinema Ritrovato, organized annually by the Cineteca del Comune di Bologna.

To honor the 80th anniversary of Cinédia, the main Brazilian film company in the 1930s, founded by Adhemar Gonzaga, the festival will present Lábios sem beijos, directed by Humberto Mauro, the only silent film the company produced (its subsequent movies were early sound films with musical accompaniment and synchronized dialogue, followed by 100% talkies).

The musicians who will be part of the 4th Jornada Brasiliera de Cinema Silencioso are Zérró dos Santos, Daniel Szafran, Wilson Sukorski, Max de Castro, Ruggero Ruschioni, Ana Fridman, Ricky Villas, Zé Luis Rinaldi, Simone Sou, André Abujamra, Marcio Nigro, Dino Vicente, Laércio de Freitas, Eric Nowinski, Marcelo Poletto, Ricardo Reis, Gustavo Barbosa, Daniel Murray, DUO N1, Basavizi, Dante Pignatari, Ricardo Carioba, Matheus Leston, Turibio Santos, Wandi Doratiotto, Danilo and Livio Tragtenberg.

More details are available (in Portuguese), including titles and full descriptions of all films, on the festival site.