Les Bains de Diane à Milan (1896)

We return to Edward G. Turner’s 1926 reminiscences of the early days of the film business in Britain. We are still in the 1890s, and changes in the business are already necessary. Turner and colleagues discover that they have pitched their product too highly…

The Crash

We soon found out, however, that we were altogether too scientific in our entertainment. The average person could not promounce the word “kinematograph,” and, if they could, it conveyed nothing to them in the way of entertainment. They all thought it was something educational, and in those days, as to-day, the public would not pay to be educated when they wanted to be amused, and so, after three months’ touring, we returned to London sadder but wiser men, and in the process of gaining wisdom, we lost our entire capital.

On the last day of the old year 1896, three unhappy men met to discuss ways and means for carrying on or closing down – the three men being J.D. Walker, J. Mackie and E.G. Turner. Mackie was demonstrator or operator, Walker was lecturer, and myself manager and treasurer – the latter office being a mere sinecure, as there were no funds to treasure, and I had to draw upon private means to pay our way.

As the bells announced the birth of a New Year (1897), we closed the books of the North American Animated Picture Company [and] reorganised our finances by my agreeing to provide £100 (which I hoped to borrow and which I succeeded in doing). Walker agreed to take half-share, and pay for his share as and when the business permitted, and Mackie withdrew as it looked an almost hopeless proposition.

Playing to the Gallery

Our policy was now altered: instead of spending a large amount of money in circularising all the best people in the towns and villages, by means of very good stationery, excellent printing and sending and sealing our letters with a penny stamp so as to attract the attention of the recipient, we went for the working classes. The results of our fresh policy was that, when the performance began, we had two or three people only in the stalls, our chief patronage came from the cheaper seats. So we decided to stop playing to the stalls, and in future to play to the gallery. From this date we were known as Walker and Turner.

On January 1, 1897, we visited the Central Working Men’s Club and Institute in Clerkenwell Road – had an interview with the entertainment secretary, who gave us an engagement for the following Saturday night, provided we gave a show of one hour’s duration for the magnificent sum of 30s.

As we had to find two cylinders of gas, and get our apparatus to and from the hall, also take two men to do the job, one will understand that it was not a profitable transaction, but the secretary personally promised us that he would send round a letter to secretaries of all the clubs in London, invite them to be present, and if our show was all we claimed it to be, there were prospects of good bookings to be obtained.

The secretary carried out his promise, and on Saturday night, when we arrived to do our show, the hall was packed to suffocation. The pictures projected were most enthusiatically received, and after the show was over we had the satisfaction of booking up dates amounting to over £200.

As we executed these dates, which were all close, others rolled in upon us from all parts of the country, principally from working men’s clubs, and that was the first step towards success; in three months our business had grown to such an extent that we had two machines operating.

Turner now moves on to some of the strategies of exhibition in the 1890s, interestingly revealing that gaps in the programme and the common practice of running films backwards were employed to spin out meagre, expensive films. He then describes the innovation in film business practice that he was central in introducing – renting, or film distribution.

A Shilling a Foot

In those days we were paying 1s. per foot for our films, the average length being 500 feet. It will, therefore, be understood that the cost of running an hour’s programme was very expensive.

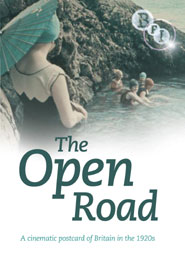

It is true that to eke out our meagre supply of films we used to take a minute or two between the change, and further, we had what was known as a reversing prism, and, after we had shown a film through, e.g., “The High Divers at Milan” (which was a very effective subject for the purpose), we would then rewind the film, put it through the machine backwards, and, by means of the prism, instead of the man diving into the water from the high diving boards, there would be a splash of water, out of which the man, feet foremost, would come and go back on to the diving board – in fact, the whole subject being reversed. This used to create not only great amusement but wonder as to how it was done, and used to help us very considerably in making our programme last out the necessary time. And if they applauded, well, on went the film a second time.

The Beginning of Renting

The price of films quickly dropped from 1s. to 8d. per foot, and then became standard at 6d. a foot; this allowed us to increase our store, but it soon became evident that to have to provide new films every time we took a repeat engagement was too expensive. So we conceived the idea, first of all, of an interchange of films with other exhibitors, who experienced the same difficulties in regard to new supplies. From this we eventually evolved the renting of films to other people, because we found that we had by far a larger stock than any of the other men. By buying films regularly we could use them ourselves and hire them to the other people, and so in such small beginning was evolved the great renting system as known to-day.

The First Woman Operator

At the end of 1897 we had three machines working. Walker operated one, myself the second, and the third was handled by Mrs. J.D. Walker, though a man went with her to fit up and do the donkey work. Mrs. Walker handled the mixed gas jet and operated, and she can claim without fear of contradiction to be the first woman operator in the world. She is still in business as managing director of the Empire cinema, Watford.

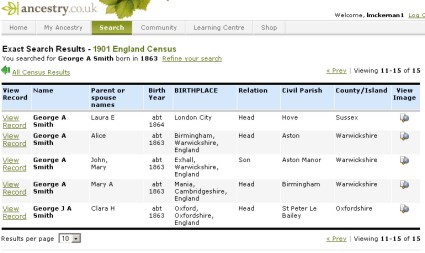

Was the redoubtable Mrs Walker the ‘first women operator in the world’? The evidence of the 1901 census, as reported in a recent post, shows that there were certainly other women operators around at the same time. More investigation is needed. ‘The High Divers of Milan’ is Les Bains de Diane à Milan (1896), Lumière catalogue no. 277, and is illustrated above. Reversing prisms, which were fitted onto the lens, were available from equipment suppliers at the time. They were used when film could not simply be reversed by cranking in the opposite direction i.e. the film had to be re-threaded in reverse, with the prism necessary to turn the image the correct way round. Is that a correct explanation, you experts out there?