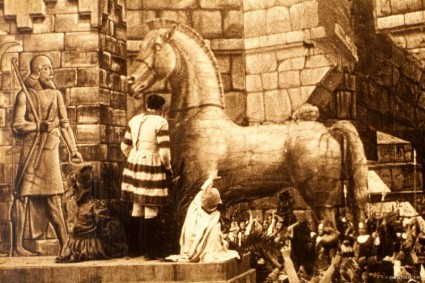

La caduta di troia (Italy 1910), from http://www.mondomostre.it

A few words of praise are in order for a marvellous early cinema event which took place in London this week. The Ancient World in Silent Cinema (which was trailed by the Bioscope a while back) tookplace at the Bloomsbury Theatre on 28 January. It was an afternoon and an evening of films from the silent era on Ancient Greek and Ancient Roman themes, organised by the University College London’s Department of Greek and Latin.

This was a significant part of the interest, that a classical studies department had undertaken to exhibit these films, offering the promise of fresh insights and new angles into material that cannot only be the preserve of we early cinema hacks. Of course, we hacks turned up an occupied the front row, but the theatre was full of some 250 or so new enthusiasts, who had for the most part never seen such films, and who were clearly thrilled at the sense of discovery. Yes there was a giggle or two, but no more giggles than Brad Pitt in Troy got – in fact, probably a good deal fewer. Stephen Horne accompanied the films in bravura style, on piano, electronic keyboard and flute. He didn’t quite manage to play all three at the same time, but he did manage two (and that’s piano and flute, folks, not just piano and second keyboard). A number I spoke to afterward couldn’t believe it was all improvised and that he hadn’t seen the films beforehand.

I only saw the afternoon screening of Ancient Greece on film, alas (if anyone attended the Roman show, do add your comments). But what a well-selected delight it was. All of the films came from the BFI National Archive. Amour d’esclave (France 1907) was an effective pocket melodrama with some poignancy behind the histrionics, as Polymos falls in love with a slave girl and prefers to take poison with her and die rather than return to his wife. In the middle came a delightfully incongruous dream sequence featuring the Pathé dancing girls. La Morte di Socrate (Italy 1909) gave us Socrates’ death by drinking hemlock, fresh from the pages of Plato, so it felt, once you’d allowed for a certain amount of arm-flailing. Elettra (Italy 1909), given an extraordinary jagged piano accompaniment by Horne, portrays the bloody revenges of Greek tragedy with enthusiastic passion.

Louis Feuillade’s La Légende de Midas (France 1910) was just wonderful. In contrast to the high tone of the previous films, here was the humour to be found in Greek myth. King Midas prefers Pan’s music to that of Apollo, so the latter punishes him by giving him asses’ ears. Midas tries desperately to hide the disfigurement under a hat, but his barber discovers the secret and has to tell someone, so he says what he knows into a hole in the ground. Reeds grow up and whisper the secret to couples passing by, who then tease the hapless Midas. It was done in such a spirit of fun, with effects that got across just the right sense of magic.

Then came La caduta di Troia (Italy 1910). What a fine filmmaker Giovanni Pastrone was, a point made all the clearer by L’Odissea (Italy 1911) which followed it, which covered the same territory with some fine special effects but none of the genius for action, spectacle and connection beween scenes that Pastrone displayed. Among the gems were Paris and Helen floating across screen on a giant seashell on their way to Troy, the wooden horse (of course), and expertly orchestrated mayhem as the Greeks pour into the city. Anyone who read Homer (or Homer-based stories) when young and remembers the thrill of character and incident that marks out the myths would have had to thrill at such dedicated attempts to recreate their look and spirit. One also saw the early cinema stretching its boundaries – more space, more people, more movement, boldness in invention,delight in the stimulus to the imagination. L’Odissea had less directorial imagination, but we had a fantastic cyclops, convincingly huge against Odysseus and his men (thanks to superimposition) and graphically blinded, and a startling Scylla and Charybdis.

It was a pity that the show was concluded by showing two fragments from Alexander Korda’s otherise lost The Private Life of Helen of Troy (USA 1927). In other circumstances this mocking burlesque would have been great fun, but here in took us into another world from that of the early cinema productions, which had so earnestly tried to recapture the thrill of the ancient world to the impressionable imagination.

As said, I missed the Ancient Rome half of the day, but for the record the films shown were Julius Caesar (USA 1908), Giulio Cesare (Italy 1909), Cléopatre (France 1910), Lo Schiavo di Cartagine (Italy 1910), Dall’amore al martirio (Italy 1910), Patrizia e Schiava (Italy 1909), A Roman Scandal (USA 1924) and Jone O Gli Ultimi Giorni di Pompei (Italy 1913).

There has been a reasonable amount written about representations of the classic world on film, but little of it devoted to the silent era. The films were being shown as part of a research project on the theme, and one of the academics involved, Maria Wyke, has written Projecting the Past: Ancient Rome, Cinema and History,which covers the silent era. Other relevant titles are David Mayer’s Playing Out the Empire: “Ben-Hur” and Other Toga Plays and Films, 1883-1908, William Uricchio and Roberta E. Pearson’s Reframing Culture: Case of the Vitagraph Quality Films.

The UCL project is to return with a second set of screenings and talks on 22 June at the Bloomsbury Theatre, when the theme will be films set in Biblical or Near Eastern Antiquity. More news on this when I have it. It will be the place to be.