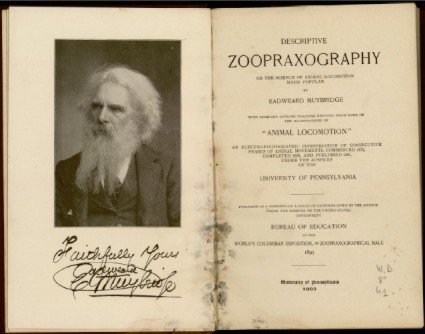

Projecting with the De Forest Phonofilm system, from The Gramophone, March 1927

It’s been a while since we’ve been able to bring you news of digitised newspapers or journals accessible online, but here’s a treat for the new year. The Gramophone, the esteemed classical music journal, has just put up in its entire archive since 1923.

It’s searchable by keyword, date range and type of item, with results refinable by decade. So searches can be narrowed to the 1920s, and there is plenty on silent cinema for us to investigate. Search results give you the item title, the first few lines, date and page number. Individual items then give you a PDF of the page (though it is necessary to register first to access these), with the option to browse further through that issue, and the OCRed text (with the occasional wobble in the character recognition). It is very easy to use,with an array of handy extras you can explore for yourselves. How it was paid for, it doesn’t say, but the service is free.

So, what will we find on silent films in The Gramophone? A surprising amount, if sometimes tangentially expressed. A good example is this piece by J.B. Hastings, from April 1925, entitled ‘The Gramophone and Film Music’, on how cue sheets were put together:

The average person will be astonished to find how much time and trouble are spent in fitting suitable music to film plays. But the big film companies have come to realise that a really good picture play can be ruined by the accompaniment of inappropriate music, and, incidentally let me whisper, they have found that even a feeble production can be made fairly, tolerable by the ingenious use of the orchestra. So, with each super film, is issued a list of ” musical suggestions,” complete with the cues and signs necessary to fit the various selections to the screen action. In many cases the actual full music score, timed to a note, is hired out with the film. Since I have had the experience of compiling a large number of such lists—I forget whether the exact number runs into millions or merely thousands—perhaps I may be permitted to indicate here how it is done.

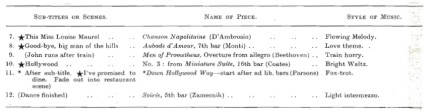

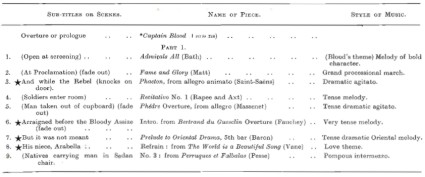

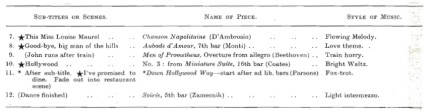

The film is projected in the cinema company’s private theatre and there I see the film with an assistant—and a stop watch. From the moment the first scene starts I am literally thinking in music. With a love scene I try to imagine just that type of sentimental melody that will exactly fit the picture, and move on in sympathy with it. A fight—then I endeavour to find an “agitato” of a tempo that will synchronise as near as possible with the speed and tensity of the film. Dramatic situations, storms, fires, sea scenes—all call for special treatment. As the film goes through, the “changes” are noted either by the sub-titles that precede them, or action on screen. In illustration of this I reproduce here a fragment of a typical “musical suggestions” sheet.

The first column contains the cues, column 2 the music and composer, column 3 the style of the piece. Those cues marked with a (*) are the opening words of the sub-titles. Brackets indicate action on screen. Both types of cue indicate a change in the action or tempo. No. 9, for instance, shows a quick change from a quiet appealing melody to a pulsating allegro. It will be easily seen that a cinema orchestral leader must be on the alert the whole time. It might almost be said that he must work with one eye on the screen and the other on his music.

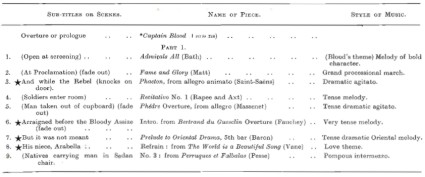

Many big photoplays call for a great number of “changes”—absolutely essential if the resultant entertainment is to be perfect. One of the most difficult films I have ever had to “fit” is Captain Blood, which is now showing throughout the country.

Mr. Rafael Sabatini’s story is so full of action and varying moods, and has been filmed with such faithfulness that no less than seventy changes are necessary, though this does. not mean seventy different selections. The chief “themes” in this story are (a) love; (b) dramatic; (e) sea battles and (ci) the “Captain Blood” theme itself. All these are there in various shades and emphasis.

As an introduction we start with the Captain Blood song, specially written as an overture or prologue. This is followed by Admirals All (Hubert Bath) and is used, in all, in eight different places.. For the love theme I have chosen The World is a Beautiful Song (Vane), and the principal seafighting scenes, Beethoven’s King Stephen overture from “presto,” varying this with various “incidental symphonies” specially written for film use.

Here is an extract from the music which I have fitted to the comparatively quiet first reel of Captain Blood:

Compare this with the smashing character of the music towards the end, when the terrific battle of Port Royal, Jamaica, is introduced. Here you will notice indication of “effects”.

Naturally, many cinemas cannot, for various reasons, follow the “official” musical suggestions in their entirety, especially as it is only in cases of exceptional films like Captain Blood that the complete score, correctly numbered and marked, can be hired from the film company.

No orchestra library under the sun can hope to contain every composition that may be wanted; and no musical director knows off-hand the exact nature of every composition in existence. It is here that the gramophone is so useful. When he finds himself “stuck” for a suitable number the musical director can always turn to the gramophone for guidance as to the style and tempo of any selection, the title of which seems to indicate possibilities. Moreover, many cinema orchestral leaders, to my knowledge, gain valuable hints from the reviews of records and music published in THE GRAMOPHONE.

In conclusion, I would say that the modern super-cinema, with its often excellent orchestra, together with the great study given to the musical side of films by cinema companies, is having a marked effect upon the musical taste of the British public.

What with this and broadcasting—both tending to familiarise the “Man in the Street” with all that is best in music—it is not surprising that the gramophone firms are experiencing what can most aptly be termed “a record boom.”

And, briefly, an editorial from April 1929 casts an interesting light on payment for musical accompaniment in cinemas, in this case involving the future composer of many a British film score, Malcolm Sargent:

Dr. Malcolm Sargent, at the age of thirty-three, has just refused to play the cinema organ for half an hour every day at 12s. 9d. a minute. This shows a more genuine horror of the instrument than even I could have fancied possible in these days of hard struggling for economic existence. What puzzles me, however, even more than Dr. Sargent’s devotion to art is why it should be worth while for a West End cinema theatre to pay £7,000 a year to any man, whatever his acrobatic and musical ability, to play their organ three times daily throughout the year for ten minutes at a session. I really should very much like to know the name of the cinema theatre which was prepared to offer this price, and I think Dr. Sargent owes it to his professional brethren with lower ideals than himself to reveal the name…

And there’s much more to discover, including some fascinating material on the coming of sound, as the illustration of the De Forest Phonofilm system at the top of this post indicates. Just type in ‘cinema’ or ‘film’ as a keyword, and start browsing.