Title of ‘The Kinetoscope of Time’, from Cornell University Library

Tales of Fantasy and Fact is an 1896 collection of short stories by James Brander Matthews. He was Professor of Literature at Columbia University, subsequently America’s first professor of drama, among whose achievements was his own theatre museum. The collection includes a remarkable story, ‘The Kinetoscope of Time’, which is the reason for adding the collection to the Bioscope Library.

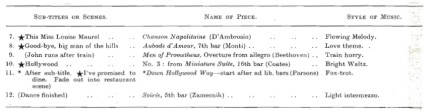

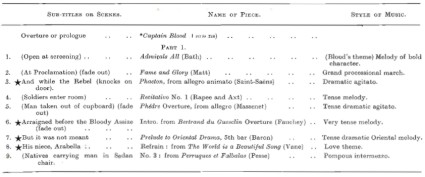

‘The Kinetoscope of Time’ was originally published in Scribner’s Magazine, December 1895. It takes the form of a Gothic horror story. The narrator finds himself at midnight in a large hall, the walls furnished with dark velvet. He comes across “four curiously shaped narrow stands”, about one foot wide and four feet high, each equipped with eye-pieces inviting the beholder to look within.

So of course he does, and he sees a succession of visions which, though they are not immediately identified as such, are the dance of Salomé, Hester Prynne and Little Pearl from The Scarlet Letter, Topsy dancing in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Nora in A Doll’s House, the fight between Achilles and Hector, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, the duel of Faust and Valentine, and Custer’s Last Stand. The narrator raises his head from these visions and is approached by a man who, though middle-aged, says that he had witnessed all these scenes, even though they mingle fact with fiction. He may or may not represent Time itself. He invites the narrator to behold two further visions, for which there will be a charge, one to witness his past, the other his future. The narrator refuses, and exists the hall to find himself in the outside world, “in a broad street”, with an electric light flashing and a train clattering by. He sees a shop window, and in it there is a portrait of the man he has just met, who is revealsed to be Cagliostro, the 18th century Italian occultist and adventurer.

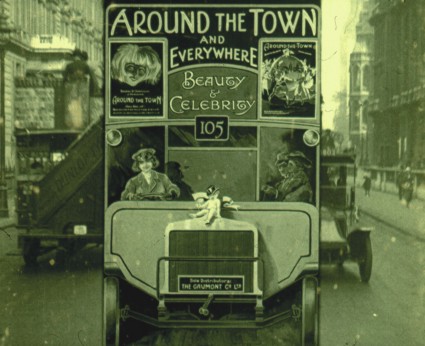

Kinetoscope parlour in San Francisco

This is a remarkable tale in a number of ways. Firstly, its Poe-like fantasy clearly takes place somewhere akin to a Kinetoscope parlour, where the Edison peepshow viewers that preceded projected film shows were placed side by side, offering a view of one film per machine. But the velvet walls, the dark of the hall and that disorienting exit into what Matthews calls “the world of actuality” seem to be a premonition of the cinemas that were to come, while the subjects are remarkably prescient, almost all of them soon to become iconic scenes in motion pictures.

But the story’s real subject is the Kinetoscope’s relationship with time. The great fascination that motion pictures held for many observers when they first appeared was their quality as a time machine. The Kinetoscope turned one, potentially, into the observer of all time – able to witness the continuum of time as events passed before one’s eye on a ribbon of film. As Mary Ann Doane writes in The Emergence of Cinematic Time:

The story conjoins many of the motifs associated with the emerging cinema and its technological promise to capture time: immortality, the denial of the radical finitude of the human body, access to other temporalities, and the issue of the archivability of time … Its rhetoric echoes that which accompanied the reception of the early cinema, with its hyperbolic recourse to the figures of life, death, immortality, and infinity. The cinema would be capable of recording permanently a fleeting moment, the duration of an ephemeral smile or glance. It would preserve the lifelike movements of loved ones after their death and constitute itself as a grand archive of time.

The story provides a metaphor for the fundamental mysteries of the moving image, in what it shows, in what it supposes it shows, and in what it supposes it is able to capture. What does it mean to represent time in any case? The cinema is a mechanical thing, a conjuror’s illusion, a Cagliostro trick. It does not portray time but rather an idea of time. The narrator does not realise this, but maybe Matthews did.

‘The Kinetocope of Time’ has been much cited down the years, and the full text is reproduced in George C. Pratt’s classic compilation of original texts about the silent cinema, Spellbound in Darkness.

Tales of Fantasy and Fact is available from the Internet Archive in PDF (17MB), b/w PDF (6.2MB), full text (219KB) and DjVu (5.2MB) formats. It is available as a single story from a number of sources – Cornell University Library‘s version reproduces the look of the individual pages from the Scribner’s Magazine original, each page (GIF image) with an illustration of the appropriate vision.