And the good things just keep on coming. A while ago the Bioscope wrote about the Cinémathèque française’s Bibliothèque numérique du cinéma, a collection of digitised books on early cinema and pre-cinema. We are slowly making our way through these to put some of them in the Bioscope Library, but now many extra titles have been added by the Cinémathèque’s distinguished historian Laurent Mannoni which demand special attention. They include film catalogues, equipment catalogues and programmes. There are 170 documents all told.

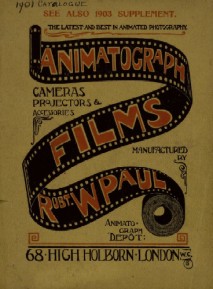

The first of these that we’re going to highlight is something quite special – a 1903 catalogue for Paul’s Animatograph Works. It is a catalogue covering the films and equipment sold by one of the leading British film producers of the period, and it is an absolute treasure trove.

The catalogue is fifty-one pages long, and it begins with an introduction to the company and its founder, Robert W. Paul. There is a short company history and photographs of the offices, laboratories, studio, dark rooms, drying rooms and more. There are details of the services provided by the company, then a special feature on their star offering, the Animatograph projector. Other equipment described includes arc lamps, lenses, limelight jets, perforators and of course cameras, with prices given.

Then come the films. These are described in some detail, and most come with frame stills, plus details of length, price and telegraph code for ordering. The catalogues includes such gems as The Automatic Machine; or, What a Surprise!, Garters versus Braces; or, Algy in a Fix and Thrilling Fight on a Scaffold:

BRICKLAYERS, labourers and carpenters are seen busily engaged on different portions of the building of PAUL’S ANIMATOGRAPH WORKS. On a high scaffold, two men are carrying hods of mortar. A quarrel arises between them, and, throwing down their hods, they fight their way along the scaffold until they reach the portion nearest the spectator. The struggle goes on until one of the two throws his mate, who falls with a fearful crash, about 30 feet to the ground. As he lies helpless, his faithful dog runs towards him, and his mates hurry up from all directions, some sliding down the poles. On examination, he proves to be seriously injured, and is only able to rise slightly. His mates help him on to a stretcher and carry him off. A thoroughly exciting picture, well appreciated by country audiences. Code word—Scaffold. Length 100 feet. Price 75s.

Now that’s product placement. Other films described include the recruiting series Army Life, a series of films of the Epsom Derby, music hall acts (including Fregoli, Chirgwin and David Devant), trick films, comedies, actuality subjects, Boer War films and ‘sensational films’, including The Last Days of Pompeii (all 65 feet of it). The volume is available as a 17MB word-searchable PDF, and makes available the kind of precious volume that researchers previously had to travels miles at great expense to find. Now it’s yours (for you can download it, of course) at the click of a mouse.

Pages from the 1903 Paul’s Animatograph Works catalogue, advertising Sensational Films

The Mannoni collection has more on Paul alone. There is a separate Army Life catalogue, a series of films of the West of Ireland and his main catalogue for 1906-07 (17MB), another forty-three pages covering Paul’s later films – without the equipment this time, but with ample details about the films (so many of them lost, of course, with this catalogue providing the only available descriptions), including wonderful illustrations and an index as well. It will have to be the subject of another post.

There are all too few early or silent film catalogues available online as yet, though the Mannoni collection has already changed that quite a little. We’ve championed the digitisation of books, newspapers and journals – now the call needs to go out for catalogues to follow. And to encourage this, we are going to introduce a new section in the Bioscope Library, for silent film catalogues and databases. This section will include the few digitised print catalogues that are out there, but it will also cover online databases.

So welcome to Catalogue Month. Yes, August (we’ve started a bit late so it’ll probably have to run into September for a bit too) is going to see the Bioscope publishing a series of posts that highlight catalogues and electronic databases freely available to all that will help you locate and identify silent films. We will describe how to find them (fairly obviously), what they contain, what they don’t contain, things to look out for, searching tips, and whatever else might come to mind. It won;t cover equipment catalogue, because I just can’t get that excited about cameras and projectors, sorry. As each one is described, a shortened account will go into the Bioscope Library under the new Catalogues and Databases section, so it’ll build up into a collection to treasure. I hope you are going to find it useful.