The 2008 Domitor conference has changed its title and varied somewhat its terms of reference. Previously it was going to be called ‘The Regional Dimension in Early Cinema’. Now it rejoices in the title ‘Peripheral Early Cinemas’. By which they seem to mean early cinema on the edges: geographically, industrially, culturally and temporally. But let them express it in their own words:

Call for Papers: Domitor 2008

The next biannual conference of Domitor will take place from Tuesday 17 June-Saturday 21 June in Catalonia, that is, Girona, Spain, and Perpignan, France. For the first time a Domitor conference will traverse national frontiers. The topic selected, appropriate for this unique setting, is:

PERIPHERAL EARLY CINEMAS

Rationale

The notion of “Peripheral cinemas” is geographical concept: cinema that is made or viewed far from the institutional center (for example, national capitals). But the designation is not only spatial. It also involves cinemas produced on the margins of developing industrial and cultural institutions.

“Peripheral” then, connotes “regional” or “provincial,” but these characterizations are relative to the specific historical period. It was Barcelona, for instance, that was the actual capital of Spanish filmmaking in 1900. Furthermore, the idea of “regional” or “provincial” is not relevant to numerous places (Italy, USA, not to mention non-Western countries).

As a result, the concept of “local cinema” becomes very problematic.

Issues and Questions envisioned

1. Institutional context. The operative conceptual tool of the Center-Periphery antinomy. To identify peripheral early cinemas reflects as well the institutional forms of centrality that were springing up. Where is the institutional “center” in early cinema?

2. Models and types of production. Can we speak of a “central model” —such as the cinema of attractions—and other “peripheral models,” such as travel films, tableaux vivants, publicity, etc…? Amateur films and military films are “peripheral” today in relation to commercial institutional production. Were they in the time of early cinema? Was women’s cinema, to the extent that it existed in the early period, peripheral?

3. The sociological level. Is there a sociological center —“bourgeois” film—for example, an English “working class” cinema? Is this distinction valid at the level of production? Reception? The two combined?

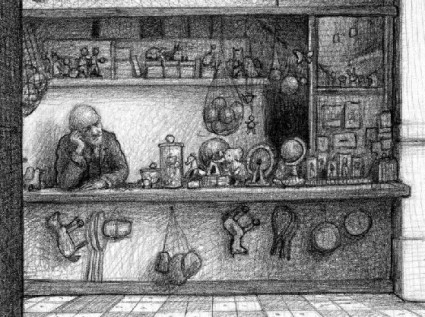

4. Industrial and peripheral exhibition systems. How did exhibition systems develop from a center? Were they aligned with specific ideas of a geographical center? Were there alternative forms of film exhibition not dependent on a center, for example in rural locations or the outskirts of large cities? Examples would be comparisons between Torino/Roma in Italy, Paris/Marseille or Paris/Nice in France or Madrid/Barcelona in Spain. Did this dichotomy function in cinematic environments everywhere, especially outside of Europe?

5. Historiography. Film history traditionally has been written from the center about the center. This is becoming less the case in recent years and relates to early cinema. Has historiography established a certain centrality in early films studies that we should consider revising? Furthermore, was it like that in the writing of the time? Is this centrality the norm in Western countries? At the same time, is the history of non-Western cinemas relegated to the periphery?

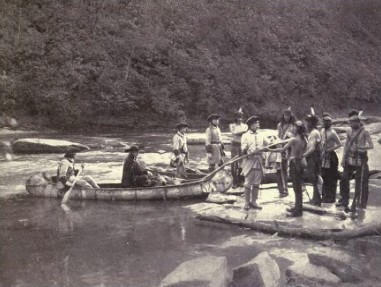

6. The study of representation: the “colonial” gaze. One puts in this category all the forms of viewing that emanate from the center to the periphery. How did that function in cinema at its origins? Peripheral and folkloric relationships? How did cinema take into account “minority” cultures at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries? The relationship of periphery to center would accordingly by first and foremost defined in terms of the gaze.

Included in this examination are “peripheral” cinematographic practices that gaze upon peripheral” cultures from outside as subjects. This would include “tourist,” “ethnographic” and neighboring filmmaking.

In order to avoid over-extending and overflowing the topic, we are not counting scientific, advertising or instructional films. Certainly, this is another issue, since one could maintain that they were “peripheral” in relation to institutional cinema.

Sending Proposals

Those wishing to submit a proposal should send a proposal of no more than one page to the selection committee by 31 December 2007. (The e-mail addresses will be posted on the Domitor website when available.) The papers must be original unpublished research. Languages accepted are English, Catalan, Spanish and French. The papers should be no more than 10 pages (A4) or 12 pages (US letter). The final text must be submitted by 30 April 2008 to allow for translation. The presentation should last no more than 20 minutes.

A selection of papers from the conference will be published in a trilingual volume.

Membership in Domitor is not required to submit a proposal. However, in order to present a paper at the conference, membership in the organization is mandatory.

Why the prejudice against scientific, advertising or instructional films, eh? There’s always something that gets pushed to the margins. And if everything’s on the edge of something else, is there a mainstream or a centre at all? Further information (if not necessarily illumination) can be found on the Domitor website. For those who don’t know, Domitor is the leading international organisation for the study of early cinema, its main activities being a bi-annual conference followed by a volume of published papers. Details of past publications from conferences going back to 1990 can be found here.

Networks of Entertainment, from http://www.johnlibbey.com

Not on the Domitor site as yet are details of the most recent publication, Networks of Entertainment: Early Film Distribution 1895-1915, edited by Frank Kessler and Nanna Verhoeff, and published by John Libbey, which derives from the 2004 conference. The publisher’s blurb describes the book thus:

This collection of essays explores the complex issue of film distribution from the invention of cinema into the 1910s. From regional distribution networks to international marketing strategies, from the analysis of distribution catalogues to case studies on individual distributors these essays written by well-known specialists in the field discuss the intriguing question of how films came to meet their audiences. As these essays show, distribution is in fact a major force structuring the field in which cinema emerges in the late 19th and early 20th century, a phenomenon with many facets and many dimensions having an impact on production and exhibition, on offer and demand, on film form as well as on film viewing. A phenomenon that continues to play a central role for early films even today, as digital media, the DVD as well as the internet, are but the latest channels of distribution through which they come to us. Among the authors are Richard Abel, André Gaudreault, Viva Paci, Gregory Waller, Wanda Strauven, Martin Loiperdinger, Joseph Garncarz, Charlie Keil, Marta Braun, and François Jost.

I thumbed through it at Pordenone, and it looks well worth getting hold of.