Lillian Gish knows just what it’s like in north Kent, from Way Down East

The snows of winter are piling up in fantastic drifts about the portals of Bioscope Towers. Icy blasts find their way through every crack and cranny. Outside, civilization grinds to a glacial halt, and the end of the year now beckons. In the relative warmth of the Bioscope scriptorium, I’ve been thinking it would be a good idea to look back on what happened in the world of silent film over 2010. So here’s a recap of highlights from the past twelve months, as reported on the Bioscope (and in a few other places) – silent memories to warm us all.

There were three really big stories in 2010. For many of us, the most welcome news story of this or any other year was the honorary Oscar that went to Kevin Brownlow for a lifetime dedicated to the cause of silent films. The restored Metropolis had its premiere in a wintry Berlin in February. It has now been screened acround the world and issued on DVD and Blu-Ray. And there was the sensational discovery by Paul E. Gierucki of A Thief Catcher, a previously unknown appearance by Chaplin in a 1914 Keystone film, which was premiered at Slapsticon in June.

It was an important year for digitised documents in our field. David Pierce’s innovative Media History Digital Library project promises to digitise many key journals, having made a good start with some issues of Photoplay. The Bioscope marked this firstly by a post rounding up silent film journals online and then by creating a new section which documents all silent film journals now available in this way. A large number of film and equipment catalogues were made available on the Cinémathèque française’s Bibliothèque numérique du cinéma. Among the books which became newly-available for free online we had Kristin Thompson’s Exporting Entertainment, and the invaluable Kinematograph Year Book for 1914.

Among the year’s restorations, particularly notable were Bolivia’s only surviving silent drama, Wara Wara, in September, while in October the UK’s major silent restoration was The Great White Silence, documenting the doomed Scott Antarctic expedition.

We said goodbye to a number of silent film enthusiasts and performers. Particularly mourned in Britain was Dave Berry, the great historian of Welsh cinema and a friend to many. Those who also left us included Dorothy Janis (who starred in The Pagan opposite Ramon Novarro); film restorer and silent film technology expert Karl Malkames; the uncategorisable F. Gwynplaine Macintyre; and film archivist Sam Kula. One whose passing the Bioscope neglected to note was child star Baby Marie Osborne, who made her film debut aged three, saw her starring career end at the age of eight, then had a further ninety-one years to look back on it all.

Arctic conditions in Rochester uncannily replicated in Georges Méliès’ A la Conquête du Pôle (1912)

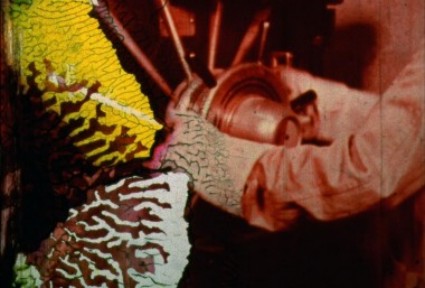

On the DVD and Blu-Ray front, Flicker Alley followed up its 2008 5-disc DVD set of Georges Méliès with a sixth disc, Georges Méliès Encore, which added 26 titles not on the main set (plus two by Segundo de Chomón in the Méliès style). It then gave us the 4-DVD set Chaplin at Keystone. Criterion excelled itself by issuing a three-film set of Von Sternberg films: Underworld (1927), The Last Command (1928) and The Docks of New York (1928). Other notable releases (aside from Metropolis, already mentioned) were Flicker Alley’s Chicago (1927) and An Italian Straw Hat (1927), Kino’s Talmadge sisters set (Constance and Norma), the Norwegian Film Institute’s Roald Amundsen’s South Pole Expedition (1910-1912) and Il Cinema Ritrovato’s Cento anni fa: Attrici comiche e suffragette 1910-1914 / Comic Actresses and Suffragettes 1910-1914, while the Bioscope’s pick of the growing number of Blu-Ray releases is F.W. Murnau’s City Girl (1930), released by Eureka. But possibly the disc release of the year was the BFI’s Secrets of Nature, revealing the hypnotic marvels of natural history filmmaking in the 1920s and 30s – a bold and eye-opening release.

New websites turned up in 2010 that have enriched our understanding of the field. The Danish Film Institute at long last published its Carl Th. Dreyer site, which turned out to be well worth the wait. Pianist and film historian Neil Brand published archival materials relating to silent film music on his site The Originals; the Pordenone silent film festival produced a database of films shown in past festivals; the daughters of Naldi gave us the fine Nita Naldi, Silent Vamp site; while Kevin Brownlow’s Photoplay Productions finally took the plunge and published its first ever website.

The crew for Alfred Hitchcock’s The Mountain Eagle, ready for anything the elements can throw at them

Among film discoveries, in March we learned of the discovery of Australia’s earliest surviving film, the Lumière film Patineur Grotesque (possibly October 1896); in June we heard about a major collection of American silents discovered in New Zealand; and digital copies of ten American silents held in the Russian film archive were donated to the Library of Congress in October. That same month the Pordenone silent film festival unveiled the tantalising surviving frgament of F.W. Murnau’s Marizza, Genannt die Schmuggler-Madonna (1921-22). There was also time for films not yet discovered, as the BFI issued its Most Wanted list of lost films, most of them silents, while it also launched an appeal to ‘save the Hitchcock 9” (i.e. his nine surviving silents).

The online silent video hit of the year was quite unexpected: Cecil Hepworth’s Alice in Wonderland (1903) went viral after the release of the Tim Burton film of Lewis Carroll’s story. It has had nearly a million views since February and generated a fascinating discussion on this site. Notable online video publications included UCLA’s Silent Animation site; three Mexican feature films: Tepeyac (1917), El tren fantasma (1927) and El puño de hierro (1927); and the eye-opening Colonial Films, with dramas made in Africa, contentious documentaries and precious news footage.

2010 was undoubtedly the year of Eadweard Muybridge. There was a major exhibition of the photographer’s work at Tate Britain and another at Kingston Museum (both still running), publications including a new biography by Marta Braun, while Kingston produced a website dedicated to him. He also featured in the British Library’s Points of View photography exhibition. There was also controversy about the authorship of some of Muybridge’s earliest photographs, and a somewhat disappointing BBC documentary. In 2010 there was no avoiding Eadweard Muybridge. Now will the proposed feature film of his life get made?

Ernest Shackleton’s ship Endurance trapped in the Medway ice, from South (1919)

It was an interesting year for novel musical accompaniment to silents: we had silent film with guitars at the New York Guitar Festival; and with accordions at Vienna’s Akkordeon festival. But musical event of the year had to be Neil Brand’s symphonic score for Alfred Hitchcock’s Blackmail (1929), given its UK premiere in November.

Noteworthy festivals (beyond the hardy annuals of Pordenone, Bologna, Cinecon etc) included the huge programme of early ‘short’ films at the International Short Film Festival at Oberhausen in April/May; and an equally epic survey of Suffragette films in Berlin in September; while the British Silent Film Festival soldierly on bravely despite the unexpected intervention of an Icelandic volcano.

On the conference side of things, major events were the Domitor conference, Beyond the Screen: Institutions, Networks and Publics of Early Cinema, held in Toronto in June; the Sixth International Women and Film History Conference, held in Bologna also in June; and Charlie in the Heartland: An International Charlie Chaplin Conference, held in Zanesville, Ohio in October.

It wasn’t a great year for silent films on British TV (when is it ever?), but the eccentric Paul Merton’s Weird and Wonderful World of Early Cinema at least generated a lot of debate, while in the US sound pioneer Eugene Lauste was the subject of PBS’s History Detectives. Paul Merton was also involved in an unfortunate spat with the Slapstick festival in Bristol in January over who did or did not invite Merton to headline the festival.

The art of the silent film carried on into today with the feature film Louis (about Louis Armstrong’s childhood), and the silent documentary feature How I Filmed the War. Of the various online modern silent shorts featured over the year, the Bioscope’s favourite was Aardman Animation’s microscopic stop-frame animation film Dot.

Charlie Chaplin contemplates the sad collapse of Southeastern railways, after just a few flakes of snow, from The Gold Rush

What else happened? Oscar Micheaux made it onto a stamp. We marked the centenary of the British newsreel in June. In October Louise Brooks’ journals were opened by George Eastman House, after twenty-five years under lock and key. Lobster Films discovered that it is possible to view some Georges Méliès films in 3D.

And, finally, there have been a few favourite Bioscope posts (i.e. favourites of mine) that I’ll give you the opportunity to visit again: a survey of lost films; an exhaustively researched three-part post on Alfred Dreyfus and film; the history of the first Japanese dramatic film told through a postcard; and Derek Mahon’s poetic tribute to Robert Flaherty.

It’s been quite a year, but what I haven’t covered here is books, largely because the Bioscope has been a bit neglectful when it comes to noting new publications. So that can be the subject of another post, timed for when you’ll be looking for just the right thing on which to spend those Christmas book tokens. Just as soon as we can clear the snow from our front doors.

And one more snowy silent – Abel Gance’s Napoléon recreates the current scene outside Rochester castle, from http://annhardingstreasures.blogspot.com