At the recent British Silent Film Festival a walk was organised for delegates around some of central London’s early film sites. With the kind permission of the walk’s organiser and guide, Ian Christie, the Bioscope is able to reproduce his notes, and encourages you (should you be in London) to follow in these footsteps. The contemporary pictures are by Matthew Lloyd. The text is followed by a review of the walk from Kelly Robinson, to whom my thanks for suggesting the idea for this post. Hyperlinks in bold are to map references. Happy trails.

(Very) Early Film Sites in Central London

1. We start in Leicester Square, beside the Chaplin statue (John Doubleday, 1981) and the Shakespeare monument (copied from Westminster Abbey, 1874), looking around the perimeter, first at the Empire (1884), site of the first Lumière Cinématographe run in Spring 1896; also at the site of the Alhambra music hall (1858) where R.W. Paul ran a competing show featuring his ‘Animatograph’, also starting in 1896 (image from http://www.arthurlloyd.co.uk). Paul also shot his first fiction film on the roof of the Alhambra. The Odeon West End opened in 1930 as one of the new sound-era cinemas (refurbished 1968) and the flagship Odeon Leicester Square opened in 1937, and remains London’s leading ‘red carpet’ venue.

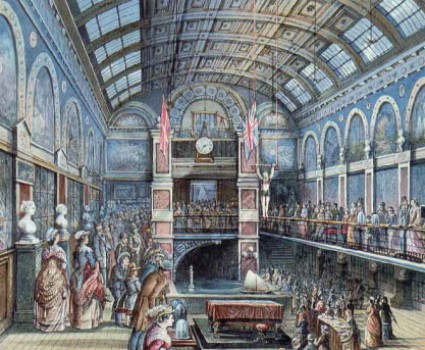

Into Leicester Place, north of main square, to look at French Catholic Church, Notre Dame de France, first built in 1865 on site of Robert Mitchell’s 1793-4 Panorama. Look north into Lisle Street, where De Loutherbourg ran the Eidophusikon in February 1781, described as ‘Moving pictures, representing phenomena of nature’. Review of Leicester Square history and entertainments since 18th century.

2. Out of Square at bottom, across Charing Cross Road, into Cecil Court once known as ‘Flicker Alley’, when it housed many early film companies, from 1897 to 1910 (detailed list in Simon Brown’s article, in Film Studies no. 10).

3. From Cecil Court, right into St Martin’s Lane, towards Trafalgar Square – noting location from which Wordsworth Donisthorpe shot frames of film in 1890.

Cecil Court and Trafalgar Square today

4. Then left into the Strand, to the site of Edison’s Kinetoscope parlour, opened on left of Adelphi Theatre in 1895 (not current Adelphi building).

5. Next to Adelphi Theatre, the Hotel Cecil, where W.K.L. Dickson lived from 1897 until his departure for South Africa.

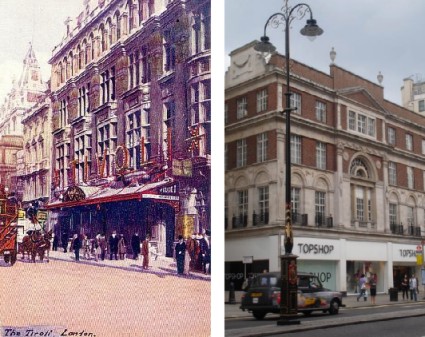

6. 64 Strand, where Dickson had his first lab, c.1903; and the site of the Tivoli Music Hall then Theatre, 65-70 Strand – which eventually became a cinema where the Film Society first met in the 1920s, but had the Biograph studio behind it in 1897.

A postcard for the Tivoli Theatre, sent in 1908, from http://www.arthurlloyd.co.uk, and the site where the Tivoli stands today

7. We turn off the Strand and head up through Covent Garden, noting site Jury’s Imperial Pictures, 142 Long Acre. Then on to St Giles Circus and crossroads of Tottenham Court Road and Oxford Sreet, to site of the Horse Shoe Hotel where the Kinetoscope launch dinner was held on 17 October 1894 (copy of the menu in the Bill Douglas Centre collection).

8. Then along Oxford Steet, looking out for no. 70, the original London Kinetoscope parlour, and the site of Hales Tours of the World, at 165 Oxford Street, from 1906.

9. We turn back into Wardour Street and identifying a series of sites associated with Charles Urban and other British pioneer producers and distributors. At the bottom of Wardour Street, we note Gerrard Street, another site of early companies such as Cricks and Martin), and Birt Acres’ Kineopticon, at 2 Piccadilly Mansions (“Britain’s first cinema” in 1896), also the Biograph offices nearby at 18-19 Great Windmill Street and Rupert and Denman Streets, where many early film businesses were based (see London Project website at http://londonfilm.bbk.ac.uk)

W.K.L. Dickson’s lab in Denman Street, image courtesy of Paul Spehr

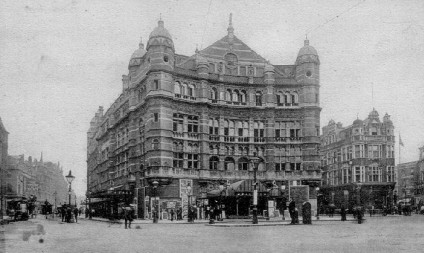

10. Then back up Shaftesbury Avenue to Cambridge Circus, where the Palace Theatre was first the home of Biograph exhibition, then of Urban’s Kinemacolor.

The Palace Theatre in the early 1900s, from http://www.arthurlloyd.co.uk

11. Finally, we finish in the Montagu Pyke public house, named after the early London cinema entrepreneur (and much else besides!).

Ian Christie

Birkbeck College – London Screen Study Collection, The London Project www.ianchristie.org

After apprehensively checking the weather forecast every day leading up to the walk we were all delighted that despite thunderstorms in the early morning it had cleared and the sun was shining. Ian Christie, our expert guide, had unfortunately various noises to contend with at the beginning including loud speakers at the Chaplin statue in Leicester Square, blaring all manner of strange sounds directly at us, and bells chiming at St Martin in the Fields. However, the walk was a delight – uncovering a hidden layer of London’s history that many of us were unaware of, including a Cocteau mural in the French Catholic Church in Leicester Place. It was a particular delight to imagine Cecil Court as ‘Flicker Alley’ a hustling and bustling street of film-related businesses before a fire encouraged relocation. With added impromptu contributions from W.K.L. Dickson’s biographer Paul Spehr and silent film historian and filmmaker Kevin Brownlow, the day was a spectacular treat. Down Wardour Street the gathering clouds could hold off no longer and we fought a torrential downpour. Luckily we were nearing the end of our walk and the Montagu Pyke pub our final destination and named after the rogue cinema entrepreneur. I’m looking forward to visiting these streets again and recollecting Ian’s anecdotes; my perception of London has certainly been transformed. Many thanks to Ian Christie and Bryony Dixon.

Kelly Robinson

British silent film enthusiasts on their walking tour of London, 7 June 2009. Photograph courtesy of Christian Hayes