The Silent Film Bookshelf was started by David Pierce in October 1996 with the noble intention of providing a monthly curated selection of original documents on the silent era (predominantly American cinema), each on a particular theme. It ended in June 1999, much to the regret to all who had come to treasure its monthly offerings of knowledgeably selected and intelligently presented transcripts. The effort was clearly a Herculean one, and could not be sustained forever, but happily Pierce chose to keep the site active, and there it still stands nine years later, undeniably a web design relic but an exceptional reference resource. Its dedication to reproducing key documents helped inspire the Library section of this site, and it is a lesson to us all in supporting and respecting the Web as an information resource.

Below is a guide to the monthly releases (as I guess you’d call them), with short descriptions.

October 1996 – Orchestral Accompaniment in the 1920s

Informative pieces from Hugo Riesenfeld, musical director of the Rialto, Rivoli and Critierion Theaters in Manhattan, and Erno Rapee, conductor at the Capitol Theater, Manhattan.

November 1996 – Salaries of Silent Film Actors

Articles with plenty of multi-nought figures from 1915, 1916 and 1923.

December 1996 – An Atypical 1920s Theatre

The operations of the Eastman Theatre in Rochester, N.Y.

January 1997 – “Blazing the Trail” – The Autobiography of Gene Gauntier

The eight-part autobiography (still awaiting part eight) of the Kalem actress, serialised over 1928/1929 in the Women’s Home Companion.

February 1997 – On the set in 1915

Photoplay magazine proiles of D.W. Griffith, Mack Sennett and Siegmund Lubin.

March 1997 – Music in Motion Picture Theaters

Three articles on the progress of musical accompaniment to motion pictures, 1917-1929.

April 1997 – The Top Grossing Silent Films

Fascinating articles in Photoplay and Variety on production finance and the biggest money-makers of the silent era.

May 1997 – Geraldine Farrar

The opera singer who became one of the least likely of silent film stars, including an extract from her autobiography.

June 1997 – Federal Trade Commission Suit Against Famous Players-Lasky

Abuses of monopoly power among the Hollywood studios.

July 1997 – Cecil B. DeMille Filmmaker

Three articles from the 1920s and two more analytical articles from the 1990s.

August 1997 – Unusual Locations and Production Experiences

Selection of pieces on filmmaking in distant locations, from Robert Flaherty, Tom Terriss, Frederick Burlingham, James Cruze, Bert Van Tuyle, Fred Leroy Granville, H.A. Snow and Henry MacRae.

September 1997 – D.W. Griffith – Father of Film

Rich selection of texts from across Griffith’s career on the experience of working with the great director, from Gene Gauntier, his life Linda Arvidson, Mae Marsh, Lillian Gish and others.

October 1997 – Roxy – Showman of the Silent Era

S.L. Rothapfel, premiere theatre manager of the 1920s.

November 1997 – Wall Street Discovers the Movies

The Wall Street Journal looks with starry eyes at the movie business in 1924.

December 1997 – Sunrise: Artistic Success, Commercial Flop?

Several articles documenting the marketing of a prestige picture, in this case F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise.

January 1998 – What the Picture Did For Me

Trade publication advice to exhibitors on what films of the 1928-1929 season were likely to go down best with audiences.

February 1998 – Nickelodeons in New York City

The emergence of the poor man’s theatre, 1907-1911.

March 1998 – Projection Speeds in the Silent Film Era

An amazing range of articles on the vexed issue of film speeds in the silent era. There are trade paper accouncts from 1908 onwards, technical papers from the Transactions of Society of Moving Picture Engineers, a comparative piece on the situation in Britain, and overview articles from archivist James Card and, most importantly, Kevin Brownlow’s key 1980 article for Sight and Sound, ‘Silent Films: What was the right speed?’

April 1998 – Camera Speeds in the Silent Film Era

The protests of cameramen against projectionsts.

May 1998 – “Lost” Films

Robert E. Sherwood’s reviews of Hollywood, Driven and The Eternal Flame, all now lost films (the latter, says Pierce, exists but is ‘incomplete and unavailable’).

June 1998 – J.S. Zamecnik & Moving Picture Music

Sheet music for general film accompaniment in 1913, plus MIDI files.

July 1998 – Classics Revised Based on Audience Previews

Sharp-eyed reviews of preview screenings by Wilfred Beaton, editor of The Film Spectator, including accounts of the preview of Erich Von Stroheim’s The Wedding March and King Vidor’s The Crowd, each quite different to the release films we know now.

August 1998 – Robert Flaherty and Nanook of the North

Articles on the creator of the staged documentary film genre.

September 1998 – “Fade Out and Fade In” – Victor Milner, Cameraman

The memoirs of cinematographer Victor Milner.

October 1998 – no publication

November 1998 – Baring the Heart of Hollywood

Somewhat controversially, a series of articles from Henry Ford Snr.’s anti-Semitic The Dearborn Independent, looking at the Jewish presence in Hollywood. Pierce writes: ‘I have reprinted this series with some apprehension. That many of the founders of the film industry were Jews is a historical fact, and “Baring the Heart of Hollywood” is mild compared to “The International Jew.” [Another Ford series] Nonetheless, sections are offensive. As a result, I have marked excisions of several paragraphs and a few words from this account.’

December 1998 – Universal Show-at-Home Libraries

Universal Show-At-Home Movie Library, Inc. offered complete features in 16mm for rental through camera stores and non-theatrical film libraries.

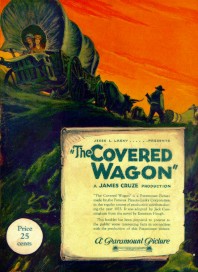

January 1999 – The Making of The Covered Wagon

Various articles on the making of James Cruze’s classic 1923 Western.

February 1999 – From Pigs to Pictures: The Story of David Horsley

The career of independent producer David Horsley, who started the first motion picture studio in Hollywood, by his brother William.

March 1999 – Confessions of a Motion Picture Press Agent

An anonymous memoir from 1915, looking in particular at the success of The Birth of a Nation.

April 1999 – Road Shows

Several articles on the practive of touring the most popular silent epics as ‘Road Shows,’ booked into legitimate theatres in large cities for extended runs with special music scores performed by large orchestras. With two Harvard Business School analyses from the practice in 1928/29.

May 1999 – Investing in the Movies

A series of articles 1915/16 in Photoplay Magazine examining the risks (and occasional rewards) of investing in the movies.

June 1999 – The Fabulous Tom Mix

A 1957 memoir in twelve chapters by his wife of the leading screen cowboy of the 1920s.

And there it ended. An astonishing bit of work all round, with the texts transcribed (they are not facsimiles) and meticulously edited. Use it as a reference source, and as an inspiration for your own investigations.