Il Cinema Ritrovato, the festival sponsored by the Mostra Internazionale del Cinema Libero and the Cineteca del Comune di Bologna, invites film lovers from around the world to Bologna from Saturday June 27th through Saturday July 4th, 2009. Eight days and evenings of cinephilic joy to be experienced in various locations: the twin screens of the Cineteca’s Lumière cinemas, one dedicated just to silent cinema, the other to sound; the Bologna Opera House and the Arlecchino Cinema (where we can experience the miracle of big screen projection as films were meant to be seen, but almost never are these days).

Let’s get started with some of this year’s titles. We pay homage to certain films simply because they have a special place in film lovers’ memory: Michael Powell’s and Emeric Pressburger’s The Red Shoes in its splendid new Technicolor restoration by UCLA Film & Television Archive with The Film Foundation; a brand new restoration of Sergio Leone’s The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (for the closing night); Make Way for Tomorrow (Leo McCarey, 1937), the predecessor of Ozu’s Tokyo Monogatari and its equal as a deeply emotional experience.

As always, evening screenings with a live orchestra promise to be some of the most exciting events: Timothy Brock, with a new score for the print restored by Cinémathèque française of Marcel L’Herbier’s Feu Mathias Pascal, the greatest Pirandello film; and Otto Donner, the grand maestro of Scandinavian jazz, with King Vidor’s The Crowd. Of course, there are also films that will be shown because they have been forgotten for too long such as Village of Sin by Ol’ga Preobraženskaja (1927), a rural melodrama and a key film from a particularly rich period of Soviet silent cinema.

The director of the year is the great Italian-American Frank Capra: his entire silent output, of which amazingly little is known today. We will be enchanted by works from the already fully-formed comic mastermind during Capra’s silent period, with their incisive view of social life and without the ready-made formulas of his later years. We will also dive into the dynamic, original and little-known beginning of his first 8 sound films, culminating in decisive masterpieces like Platinum Blonde and The Bitter Tea of General Yen. The program was created in full partnership with Sony-Columbia and with the participation of scholar and screenwriter Joseph McBride.

Vittorio Cottafavi is comparable to Sirk or Fassbinder or Leone in his capacity to treat any marginal genre with respect, literary sophistication, visual flair (with beautiful ideas about space, irony and rhythm) and a deeply nuanced popular sensibility which he lavished upon everything he touched, especially historical subjects and the peplum, which in his hands became a noble genre. The series of 12 films is curated by Adriano Aprà and Giulio Bursi.

The pleasure dome of the Arlecchino Cinema will offer two special sections: CinemaScope, widening horizons for the sixth year in a row, and color, the beginning of something that will bless our programs for some years to come. Our CinemaScope selection offers treasures like The Track of the Cat (William Wellman’s strange western with an even stranger color concept) and three famous epic movies by Vittorio Cottafavi. The first session dedicated to color is an introduction to the most notable uses of color during the first 50 years of cinema history, including the oldest hand-painted films, like masterpieces from Méliès and de Chomón, the first full color systems (Gaumont Chronochrome, Kinemacolor), tinted films, early Technicolor (in films like Scherzinger’s Redskin) and of course the miracle of the full three-strip Technicolor, both through restorations using contemporary film stock and in examples of original prints that have survived from its glory days. In other words, unforgettable viewing: Drums along the Mohawk (Ford), Pandora and the Flying Dutchman (Lewin), and of course The Red Shoes.

One Hundred Years Ago, a time travel journey that began 6 years ago, will again showcase the most exciting documentaries and fiction films about the life and imagination of people who lived exactly one century ago, with two special features: an homage to the miracle of Méliès and a reconstruction of the very first film festival in history, which took place, of course, in 1909. Mariann Lewinsky is this section’s curator.

Among the silent highlights we’ll present two small-scale portraits of notable personalities. First up is director Eleuterio Rodolfi (1876-1933), who started as an actor and later became a director of a number of films, including the celebrated 1917 version of Hamlet. And Anita Berber (1899-1928), who was a legendary, androgynous figure of Weimar Berlin: an actress, nude dancer, writer, celebrated in a portrait painted by Otto Dix, and equally impressive in the surviving examples of her appearances on screen.

Chaplin’s influence was unlimited and can be seen in the high quality of his assistants’ work. After Monta Bell last year, we present an equally creative mind, Harry d’Abbadie d’Arrast, with his two most remarkable films, A Gentleman of Paris (1927) and Laughter (1930).

Mornings too will have a special start: a full pack of Maciste, thanks to the restorations of seven films in collaboration with Museo Nazionale del Cinema di Torino. The Italian superman was a personification of the mythical hero adventuring in the past or right in the middle of modern times – the first and arguably the greatest of all the strong men of film history. The films, celebrated by Fellini and others, are totally fascinating as such, and moreover present a kind of synthesis of the film history of their day, combining – as Vittorio Martinelli put it – elements of Méliès and Lang, Gustave Doré and Flash Gordon…

Sponsored by the Cinémathèque de Toulouse and Gosfilmofond, curated by Valérie Pozner and Natacha Laurent, Kinojudaica is a series on Russian and Soviet films featuring Jewish actors, directors and themes, presenting little-known films from masters and equally fascinating films from filmmakers doomed to remain in total obscurity because of circumstances or because the films were forbidden for what seemed an eternity. Kinojudaica presents a rich flowering of Jewish films made in Russia and the Soviet Union: four silent programs and three little known sound films like Frontier by Michail Dubson (1935), The Return of Nathan Becker by Boris Špis and Rašel Mil’man (1931) and Nepokoronnye (The Taras Family) by Marc Donskoï (1945), with its terrifying re-creation of Babi Yar on screen.

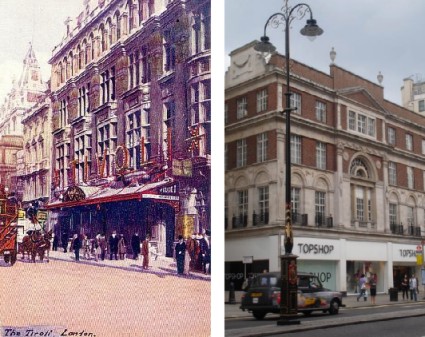

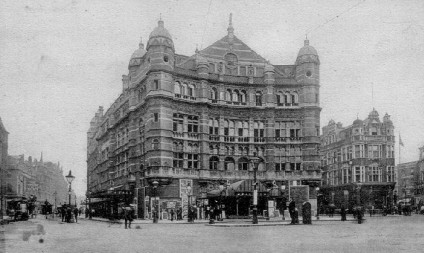

Then there are films that offer a cross-section of life, with 10-15 people from all walks of society who encounter each other in situations without any clear-cut protagonist. For unknown reasons, British cinema made this a subgenre all its own, with films like Rome Express (Walter Forde, 1932), Friday the Thirteenth (Victor Saville, 1933), The Passing of the Third Floor Back (Berthold Viertel, 1935), culminating with Carol Reed’s finest 1930s film, Bank Holiday (1938).

Richard Leacock will be our guest this year. The cameraman of Flaherty’s film, Louisiana Story, and as such a bridge between the greatest tradition and the new heights of “direct cinema”, Leacock will present his own masterpiece, A Portrait of Stravinsky.

The cinema of Vichy gives us a glimpse into that enigmatic, paradoxical period of French film, with the reconstruction of an entire program from April 17, 1942, feature films, short propaganda films from 1940-44, official Vichy and other collaborationist materials, and resistance films. This program was curated by Eric Le Roy with Les Archives Françaises du Film.

Last year’s von Sternberg series was such an astounding success that we can’t imagine it being over: so this year we are offering the master’s most sublime film of his later years (The Shanghai Gesture, the perfect Dietrich film without Dietrich) as well as a selection of fabulous footage from I Claudius, a film that was never finished and that still haunts the world’s cinephiles. And we will see Von Sternberg at work once again in an interview by Eric de Kuyper for Belgian TV.

The underlying theme of this all is again cinephilia, the absolute love of cinema. Several programs will be dedicated to this theme: films on notable personalities (Bernard Chardère, Henri Langlois’s television interviews), the unsurpassed Cinéastes de notre temps programs by André S. Labarthe.

The festival also sponsors the Film Publishing Fair (Books, DVDs, Antiquarian and Vintage Materials) and Il Cinema Ritrovato DVD Award (6th edition). We would like to remind you that Il Cinema Ritrovato will host two seminars: the continuation of the Film Restoration Summer School / FIAF Summer School 2009, organized by the Cineteca di Bologna, and a workshop for European cinema exhibitors organized by Europa Cinemas and Progetto Schermi e Lavagne. Enrollment in each seminar requires separate registration, available on this website.

On a sadder note, funding for our festival has been cut drastically, so we unfortunately have had to rethink the hospitality we can offer to our very dear public. The rates agreed on with various hotels in the city are still very advantageous, and we hope that the films we are showing this year will convince you to be with us once again this year.

You are most cordially welcomed to the most memorable eight days of 2009.

Artistic Director of Il Cinema Ritrovato

Peter von Bagh

Martedì 30 giugno

THE CROWD (La folla) Stati Uniti, 1928 Regia: King Vidor

Accompagnamento dal vivo del gruppo Jazz di Otto Donner

Giovedì 2 luglio

Progetto Chaplin

A DAY’S PLEASURE (Una giornata di vacanza) Stati Uniti, 1919 Regia: Charles Chaplin

SUNNYSIDE (Charlot in campagna) Stati Uniti, 1919 Regia: Charles Chaplin

ONE WEEK (Una settimana) Stati Uniti, 1921 Regia: Buster Keaton

Accompagnamento dal vivo diretto da Timothy Brock

Domenica 28 giugno

FEU MATHIAS PASCAL (Il fu Mattia Pascal) Francia, 1926 Regia: Marcel L’Herbier

Accompagnamento dal vivo dell’Orchestra del Teatro Comunale diretta da Timothy Brock

Cento anni fa: i film del 1909 – programmi a cura di Mariann Lewinsky

Omaggio a Eleuterio Rodolfi, Anita Berber e Georges Méliès

Frank Capra: il nome sopra il titolo

VISITA INCROCIATORE ITALIANO A SAN FRANCISCO Stati Uniti, 1921 Regia: Frank Capra

FULTA FISHER’S BOARDING HOUSE Stati Uniti, 1922 Regia: Frank Capra

THE STRONG MAN (La grande sparata) Stati Uniti, 1926 Regia: Frank Capra

LONG PANTS (Le sue ultime mutandine) Stati Uniti, 1927 Regia: Frank Capra

THAT CERTAIN THING (Quella certa cosa) Stati Uniti, 1928 Regia: Frank Capra

SO THIS IS LOVE? (Dunque è questo l’amore?) Stati Uniti, 1928 Regia: Frank Capra

THE MATINEE IDOL (Il teatro di Minnie) Stati Uniti, 1928 Regia: Frank Capra.

THE WAY OF THE STRONG (La maniera del forte) Stati Uniti,1928 Regia: Frank Capra

SUBMARINE (Femmine del mare) Stati Uniti,1928 Regia: Frank Capra

THE YOUNGER GENERATION (La nuova generazione) Stati Uniti, 1929 Regia: Frank Capra

THE DONOVAN AFFAIR (L’affare Donovan) Stati Uniti, 1929 Regia: Frank Capra

Kinojudaica, l’immagine degli ebrei nel cinema russo e sovietico

OÙ EST LA VÉRITÉ? (Vu iz emes?) URSS, 1913 Regia: Semion Mintus

LE MALHEUR DE SARAH (Gorrié Sarry) URSS, 1915 Regia: Alexandre Arkatov

LÉON DREY URSS, 1915 Regia: Evgueni Bauer

VÉRA TCHЕBЕRIAK URSS, 1917 Regia: Nikolaï Brechko-Brechklovski

CONTRE LA VOLONTÉ DES PÈRES (Protiv voli otsov) URSS, 1926-27 Regia: Evgueni Ivanov-Barkov

LES CINQ FIANCÉES (Piat nevest) URSS, 1929-30 Regia: Alexandre Soloviev

RETENEZ LEURS VISAGES (Zapomnite ikh litsa) URSS, 1929-30 Regia: Ivan Mutanov

Tutto Maciste

MACISTE (IL TERRORE DEI BANDITI) Italia, 1915 Regia: Luigi Romano Borgnetto,V. Denizot

MACISTE ALPINO Italia, 1916 Regia: Luigi Romano Borgnetto

MACISTE INNAMORATO Italia, 1919 Regia: Luigi Romano Borgnetto

MACISTE IN VACANZA Italia, 1920 Regia: Luigi Romano Borgnetto

MACISTE ALL’INFERNO Italia, 1925 Regia: Guido Brignone

MACISTE NELLA GABBIA DEI LEONI Italia, 1926 Regia: Guido Brignone

MACISTE CONTRO LO SCEICCO Italia, 1926 Regia: Mario Camerini

Jean Epstein, il mare come definizione del cinema

FINIS TERRAE Francia, 1929 Regia: Jean Epstein

MOR VRAN Francia, 1931 Regia: Jean Epstein

Dossier Chaplin e Napoleone

Omaggio a Harry d’Abbadie Arrast

Dossier Metropolis

Dossier Blasetti

La crisi economica ai tempi del muto