Asta Nielsen playing a suffragette undergoing forcefeeding in Die Suffragette (1913), from Stiftung Deutsche Kinemathek

Early film reflected the society in which it arose, and there is no clearer example of this than the campaign for women’s suffrage. The movement to gain women the vote in Britain reached its climax during the period when mass cinema-going was first underway in the early 1910s, and films reflected the popular understanding of the suffragettes. The militant woman became a standard figure in early ficition films, generally portrayed for comic or satiric effect. At the same time the suffragettes were regularly covered by the newsreels, a dynamic new medium for reporting what was happening in the world to a mass audience.

The relationship between women’s suffrage and early film is explored in Frühe Interventionen: Suffragetten – Extremistinnen der Sichtbarkeit (Early interventions / Suffragettes – extremists of visibility), a series of films and lectures being held at the Zeughauskino, Berlin, 23-27 September 2010. Behind the somewhat forbidding title is a tremendous programme of rare materials uncovered from archives across Europe and curated by Madeleine Bernstorff and Mariann Lewinsky. The films document not only the suffragettes as audiences saw them in fiction and non-fiction films, but also the role of women in early cinema generally, showing how trangressive, rebellious and sometimes just plain exuberant displays by women on screen echoed the drive for changes in society of which the campaign for the vote was but a part.

The Pickpocket (USA 1913), from EYE Film Institute Netherlands

Here is the programme:

Thursday 23. September 20:00 h

Radical maid(en)s

Cheerful young girls’ break-outs, class relations and radicalisations.

Sedgwick’ s Bioscope Showfront at Pendlebury Wakes, GB 1901, 30m 1’30“

La Grêve des bonnes, France 1907 184m, 10’

Tilly in a Boarding house GB 1911 D Alma Taylor, Chrissie White 7’

Pathé newsreel The Suffragette Derby, GB 1913, ca 5’

Miss Davison’s Funeral, GB 1913, 45m 2’

A Suffragette in Spite of Himself GB 1912 Edison R: Bannister Merwin D: Miriam Nesbitt, Ethel Browning, Marc McDermott 8’, 16mm

Break

Robinette presa per nihilista Italy 1912, D: Nilde Baracchi, 124m, 8’

Cunégonde reçoit sa famille France 1912 D: Cunegonde – name unknown, 116m, 6’

Les Ficelles de Leontine France 1910, D: Leontine – name unknown, 155m, 8’

Tilly and the fire engines GB 1911 2’ D: Alma Taylor, Chrissie White

[A Nervous Kitchenmaid] France c.1908, 74m, 4’

Introduction: Madeleine Bernstorff

Live piano accompaniment by Stephen Horne.

Friday 24. September 18:00 h

The Fanaticism of the Suffragettes

Lecture with images and filmclips by Madeleine Bernstorff

Following the lecture Mariann Lewinsky will present the DVDs Cento anni fa/A hundred Years ago: European Cinema of 1909 and Cento anni fa/A Hundred Years ago: Comic Actresses and Suffragettes 1910-1914 [for more information, see end of this post].

Friday 24. September 19:00 h

Militancies

Les Femmes députées France 1912 D: Madeleine Guitty 154m 8’

England. Scenes Outside The House Of Commons 28 January 1913 2’

Trafalgar Square Riot 10 August 1913 1913 2’

Milling The Militants: A Comical Absurdity GB 1913 7’

St. Leonards Outrage France 1913 21m 1’

Womens March Trough London: A Vast Procession Of Women Headed By Mrs Pankhurst. March Through London To Show The Minister Of Munitions Their Willingness To Help In Any War War Service GB 1915 23m 1’

Scottish Women’s Hospital Of The National Union Of Women’s Suffrage Societies France 1917 133m 6’30

Dans le sous-marin France 1908 Pathé 145m 5’

Introduction: Madeleine Bernstorff

Live piano accompaniment by Stephen Horne.

Friday 24. September 21:00 h

Women’s Life and Leisure in the Mitchell & Kenyon Collection

Presented by Vanessa Toulmin

The renowned Mitchell & Kenyon Collection provides an unparalled view of life at the turn of the twentieth century and this screening will allow us an opportunity to see women’s life and leisure in industrial England. The social and political background as well as working conditions will be shown on screen. The range and sheer diversity of women in the workplace will be revealed from the domestic to the industrial environment, women played an important role in the transition to modern society. From girls working in the coal mines to spinners and weavers leaving the factory this selection from the Collection will reveal previously unseen footage from the Archive, in a following workshop Vanessa Toulmin will speak about: Discovery and Investigation: The Research Process of the Mitchell & Kenyon Collection.

Women at Work: The ‘Hands’ Leaving Work at North-Street Mills, Chorley (1900), North Sea Fisheries, North Shields (1901), Employees Leaving Gilroy’s Jute Works, Dundee (1901), S.S. Skirmisher at Liverpool (1901), Birmingham University Procession on Degree Day (1901), Life in Wexford (1902), Black Diamonds – The Collier’s Daily Life (1904)

Women in the Social Environment: Liverpool Street Scenes (1901), Jamaica Street, Glasgow (1901), Manchester Street Scenes (1901), Manchester Band of Hope Procession (1901), Electric Tram Rides from Forster Square, Bradford (1902)

Leisure and Play: Sedgwick’s Bioscope Showfront at Pendlebury Wakes (1901), Spectators Promenading in Weston Park, Sheffield (1902), Trip to Sunny Vale Gardens at Hipperholme (1901), Bootle May Day Demonstration and Crowning of the May Queen (1903), Blackpool Victoria Pier (1904), Greens Racing Bantams at Preston Whit Fair (1906), Calisthenics (c. 1905).

Live piano accompaniment by Stephen Horne.

Saturday 25. September 18:00 h

La Neuropatologia

Lecture by Ute Holl+ screening of La Neuropatologia (I 1908)

La Neuropatologia is a medical instructional film by the Turin neurologist Camillo Negri. The film can be read – utilising medical-historical methology – as the presentation of an hysterical seizure, but it could also be called an expressionist drama, a love triangle. Medical fact cannot be visualized without the medical stage, the theatre, the mise-en-scène. End of the 19th century the visual turn in medical methodology and in neurological diagnosis gets introduced.

Saturday 25. September 19:00 h

Staging and Representation: A cinematographic studio

La Neuropatologia opens the view on representational relations. The Austrian company Saturn Film produced so-called ‘titillating’ films for a male audience, but the models also had her own ideas about erotic stagings. Normal work is part of an installation, and a re-enactment of four late-19th century photographies by Hannah Cullwick, who worked as a maid and produced numerous (self)portraits as part of a sado-masochist bond with her bourgeois boss Arthur Munby.

La Neuropatologia Italy 1908 Camillo Negro 107m 5’

La Ribalta (Fragment) Italy 1913 Mario Caserini D: Maria Gasparini 60 m 3’5’

Beim Photographen Austria 1907 Saturn 50m 3’

Das eitle Stubenmädchen Austria 1907 Saturn 50m 3’

Normal Work Germany 2007 Pauline Boudry, Renate Lorenz D: Werner Hirsch 13’ 16mm/DV

Concorso di bellezza fra bambini / Kindertentoonstellung Italy 1909 80m 4’

La nuova cameriera e troppo bella Italy 1912 D: Nilde Baracchi, 138m 7’

Rosalie et Léontine vont au théâtre France 1911, D: Sarah Duhamel + Leontine – name unknown 80m, 4’

L’intrigante France 1910 Albert Capellani 162m 8’

Introduction: Madeleine Bernstorff

Live piano accompaniment

Saturday 25. September 21:00h

Glittering stars, athletic women, first star personas

From 1910 on many female comedians had their own series. There was alsoa strong presence of female artistes and performers in the cinema before 1910.

Danse Serpentine / Annabella USA c.1902 Edison ca 2’ 16mm

La Confession France 1905 D: Name nicht bekannt 60m 3’

Femme jalouse France 1907 D: Name nicht bekannt 58m 3’

Lea e il gomitolo Italy 1913 D: Lea Giunchi 99m 5’

Danses Serpentines France / USA 1898-1902 D: U.a. Annabella 60m 3’

La Valse chaloupée France 1908 D: Mistinguett, Max Dearly 38m 2’

Sculpteur moderne France 1908 R: Segundo de Chomon D: Julienne Matthieu 8’

Les Soeurs Dainef France 1902 65m 3’

Introduction: Mariann Lewinsky

Live piano accompaniment Eunice Martins

+

Zigomar peau d’anguille France 1913 Eclair Victorin Jasset D: Alexandre Aquillere, Josette Andriot, 940m 45’

On the turntables: Julian Göthe

Sunday 26. September 18:00

Re-Reading Steinach

Lecture and video-presentation by Mareike Bernien

Re-Reading Steinach is a re-assembly of the popular-science film Steinachs Forschungen by Nicholas Kaufmann/UFA from 1922 – with the idea to analyze representations of normative and divergent body-and gender-constructions in the beginning of 20th century.

Sunday 26. September 19:00

Man/woman/norm/cinema

Cross-dressings of men and women: Elegant page-uniforms and pantskirts, men in nurse-dresses and the wonderful Lotion Magique which grows beards on breasts and breasts on bald heads.

Mes filles portent la jupes-culotte France 1911 120m 6’

Monsieur et Madame sont pressés France 1901 20m 1’

Le Poulet de Mme Pipelard France 1910 84m 5’

Cendrillon ou La Pantoufle merveilleuse France 1907 R: Albert Capellani 293 m 15’

Il duello al shrapnell Italy 1908 100m 5’

La Lotion magique France 1906 Pathé 80m 5’

La Grève des nourrices France 1907 190 m 10’

Schutzmann-Lied from Metropol-Revue 1908, Donnerwetter! – Tadellos! Germany 1909 D: Henry Bender Beta 2’ (digital sound image reconstruction by Christian Zwarg)

Introduction: Mariann Lewinsky and Madeleine Bernstorff

Introduction to Schutzmannlied: Dirk Foerstner

Live piano accompaniment

Sunday 26. September 21:00

The Woman of Tomorrow

Cinema before 1910 was abundant in non-fiction films about daily work. La Doctoresse is part of a comedy-serial by Mistinguett and her partner Prince. The Russian film The Woman of Tomorrow is about a successful feminist female doctor.

Recolte du sarasin France 1908

L’Industria di carta a Isola del Liri Italy 1909 147m 7’30“

La Doctoresse France 1910, D: Mistinguett, Charles Prince 140m 7’

Zhenshchina Zavtrashnego Dnya / The woman of tomorrow Russia 1914, D: Vera Yurevena, Ivan Mosjoukine, 795m 40’

Live piano accompaniment

Monday 27. September 18:00

Political Stagings of the Suffragettes in England

Lecture by Jana Günther on strategic image politics of the militant English suffragette movement: between permanent spectacle and crusade. The Suffragettes appropriated activist strategies of the workers’ movement and tried out acts of civil inobedience like chaining themselves to railings, hunger strikes and other distruptive acts.

+ presentation of the film A Busy Day aka A Militant Suffragette D:Charlie Chaplin, USA 1914 16mm 6’

Monday 27. September 19:00h

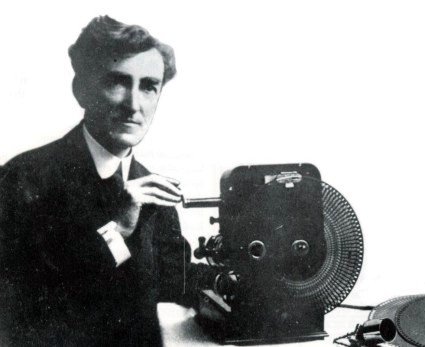

Die Suffragette

The restored version (by Stiftung Deutsche Kinemathek) of the Asta Nielsen melodrama Die Suffragette with some rediscovered scenes – including the force-feeding-scene which had been cut because of strict censorship regulations.

Bobby und die Frauenrechtlerinnen/Mijnher Baas + de vrije Vrouwen Germany 1911 Oskar Messter 112m 6’

Pickpocket USA 1913 260 m 13’

Les Résultats du féminisme France 1906 Alice Guy 5’

Die Suffragette Germany 1913 D: Asta Nielsen (Nelly Panburne) 60‘

Introduction: Karola Gramann + Heide Schlüpmann

Live piano accompaniment Eunice Martins

Monday 27. September 21:00h

The Year of the bodyguard

The film essay by Noël Burch deals with the subject of suffragettes in 1912 training under the first English female jiu-jitsu expert Edith Garrud to fight the police and protect their leaders.

Wife, The Weaker Vessel GB 1915 D: Ruby Belasco, Chrissie White, 190m 9’

Le Sorelle Bartels Italy 1910 74m 4’

The Year of the Bodyguard Noel Burch 1981 54’ ZDF

Works and Workers at Denton Holme GB 1910, 90m 5’

In the foyer of Zeughauskino there will be a video installation ‘I would be delighted to talk Suffrage’ by Austrian artist Fiona Rukschcio and a lightbox and bulletin board by Madeleine Bernstorff with materials from the National Archives, London on police spy photographs depicting the suffragettes.

Suffragette Demonstration at Newcastle, from BFI National Archive

Madeleine Bernstorff writes these words about women’s suffrage and film in the notes to the programme:

In the early twentieth century, the cause of women’s suffrage and the suffragette movement became a cinematic topic. Something seemingly untameable had appeared on the city streets, provoking a good deal of anxiety: women, often sheltered ladies of the bourgeoisie, were organising and even demanding participation in democratic processes! By 1913 more than 1,000 suffragettes had already gone to prison for their political actions. In addition to cartoons in the print media, newsreels and melodramas were produced along with countless comedies that referred – in all their ambivalence of subversion and affirmation – to the movement. They told the audience that women belonged at home and not at the ballot box, that these unleashed furies who now appeared in the streets en masse were growing mannish, neglecting their families and even setting public buildings ablaze. In the anti-suffragette films, women’s rights activists were often misguided souls who needed to be brought back to their proper calling. They also left plenty of room for nod-and-wink voyeurism on all sides. Men, too, masqueraded as suffragettes – to illustrate how inappropriate and grotesque it was for women to overstep their roles – or to act out against the prevailing order even more wildly?

The figure of the suffragette in early fiction (usually comedy- the seriousness of Asta Nielsen’s Die Suffragette is a notable exception) film is one that has been written about in several places, though never before has such an extensive collection of relevant films been seen in one place, to my knowledge. However, I would encourage those attending the event to look twice at the newsreels as well. There are many surviving newsreels showing the suffragettes – for the simple reason that they made it their business to be filmed.

The suffragettes showed themselves to be particularly media savvy by staging events that would attract the media. The simplest strategy was to organise marches with banners with bold slogans that could be easily picked up by the cameras. Then there was the obvious tactic of letting the newspapers and newsreels know beforehand of when a march or such like was going to take place. Just occasionally there was active co-operation with the newsreel companies. Rachael Low, in The History of the British Film 1906-1908, reproduces this report from the Kinematograph and Lantern Weekly 25 June 1908, p. 127, which shows how far this could go:

From certain sources whispers had reached us anent Mr. Harrison Ward’s secret conclaves with Mrs. Drummond and Miss Christabel Pankhurst, and as we surmised the plottings of the trio within the suffragette’s fortress have taken definite shape in the form of a picture history of recent performances of the ‘great shouters’ during their campaign … With exclusive right for kinematographing from the suffragists’ conning tower Mr. W. Jeapes obtained some exceptionally interesting pictures, those showing Mr. R.G. Knowles discussing the burning question with some of the leaders at the base of the tower being particularly good, the same remark applying to the life-size portraits of Mrs. ‘General’ Drummond, Miss Pankhurst and others. Mr. Jeapes and Mr. Ward probably never played to a bigger house than they did on Sunday, and the sight of the surging mass of humanity following the pantechnicon ‘conning tower’ as it emerged from Hyde Park, what time the energetic pair on top recorded the scene was something to arouse the envy of any kinematographer with an eye for picture effects.

The film, made by the Graphic Cinematograph Company, was a bit more than the average newsreel (it showed the major demonstration organised by the Women’s Social and Political Union that took place 21 June 1908 in Hyde Park). But the degree of pre-planning, co-operation and indeed the purchase of exclusive rights for a key camera position demonstrates that both news companies and suffragettes recognised the great value of one another, and that we should look on the newsreels of suffragettes as composed works rather than accidental actuality. We see what they wanted us to see.

Even when there wasn’t active co-operation with the newsreels, the suffragettes knew where cameras (still and motion picture) would be positioned, so that their protest acts would gain the greatest publicity. The best known example is that of the 1913 Derby, at which Emily Wilding Davison was killed after running onto the race-course and being knocked down by the King’s horse. The act was captured by a number of newsreels (the Pathé version is to be featured in Berlin) because they were all trained on the final bend before the end of the race, Tattenham Corner, and that is exactly where Davison chose to run out. Again, we see what they wanted us to see.

- The Gaumont Graphic version of the 1913 Derby is here

- The Pathé’s Animated Gazette version is here

- The Topical Budget version is here (accessible to UK schools and libraries only)

- (The Warwick Bioscope Chronicle version is here but I can’t make it play, and in any case Warwick either missed the incident or it has been cut from the extant film)

- There are British Pathe compilations of suffragette newsreel footage here and especially here

There isn’t any information online about the Berlin screenings as yet (apart from this post, obviously), but information will appear on the Zeughauskino site once it gets round to publishing its September programme. (Now published)

Update (4 September): The full programme is now available (in German) from www.madeleinebernstorff.de (full marks for the striking design).

Finally, the DVD from this year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato mentioned above is now available for sale. Curated by Mariann Lewinsky, Cento anni fa: Attrici comiche e suffragette 1910-1914 / Comic Actresses and Suffragettes 1910-1914 is a DVD and booklet on nineteen films (Italian, French, English, American), featuring such female comedy stars as Tilly and Sally (Alma Taylor and Chrissie White), Cunégonde, Mistinguett, Rosalie, Lea and Gigetta, plus newsreel films (including two compilations) of suffragette action from the UK and USA. The DVD is priced 19.90 € and is available from the Cineteca Bologna site. For those not able to be in Berlin it’s going to be the next best thing.

My thanks to Madeleine Bernstorff for providing the programme information and stills.