Verdi theatre, Pordenone

There’s no time for slouching at Pordenone if you are serious about your film-watching. A few habitués of the Giornate del Cinema Muto seem to have come for the sun and conversation, taking up near permanent residence in the pavement cafés, but for the rest of us breakfast was swiftly followed by the first film of the day at 9.00am sharp and the final film of the day concluding around midnight. They do let you out for lunch and dinner, but in general it’s a tough regime we had to follow.

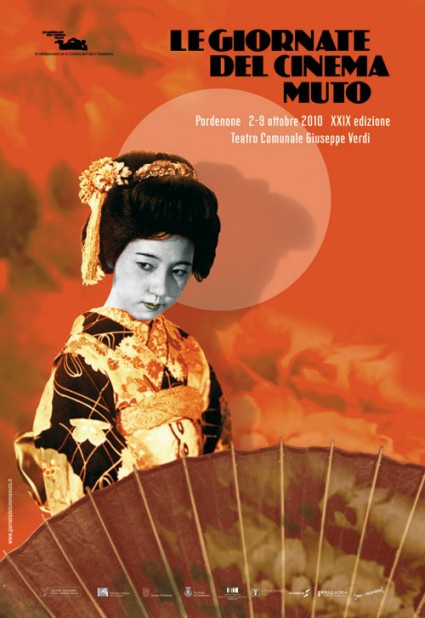

And so we move to day two, Sunday 3 October, and what was to become the daily routine of starting off with a long Japanese film, just to test our stamina. Our 9.00am offering was Nanatsu No Umi (Seven Seas) (Japan 1931-32), made in two parts and shown back-to-back over 150 minutes. The films were made by Hiroshi Shimizu, director of the previous day’s Japanese Girls at the Harbour, and there were clear similarities in preoccupations and style.

The film tells of Yumie (played by Hiroko Kawasaki) who is torn between two brothers. She is engaged to the first but seduced by the second, following which her father dies and her sister goes mad. She marries her seducer but takes her revenge by refusing to let him touch her and spending all his money on her sister’s care in a mental hospital. It was pure soap opera, with a somewhat discontinuous narrative (particularly in part 1) characterised by seemingly random elements (just who was it who committed suicide in part 1, and why?) and unclear connections between some of the characters. Then it all ended with a happy ending so rapidly organised that you suspected that a reel was missing. As with Saturday, Shimizu showed off plenty of directorial tricks but lacked the basic skill of connecting one shot with another to propel a narrative forward. But he also showed the same intriguing, codified cultural elements, dividing the action up into public lives that showed the influence of the West (clothing, occupations, the key location of a sports shop) and traditional Japanese dress and manners within the private sphere. You felt you had been given a privileged glimpse into early 1930s Japanese life in the kind of middle-brow film that doesn’t usually make it to retrospectives. Japan’s leading silent film pianist Mie Yanashita was an excellent accompanist for this and all the other Japanese films that featured in the festival.

Scenes from Rituaes e festas Borôro (1916), from http://www.scielo.br

Now these dramatic films are fine in themselves, and even the severest of film critics likes to see a story told well, but regulars will know that what really stirs the heart of the Bioscope is the non-fiction film. So I was looking forward greatly to what was next on the list – Brazilian documentaries – and was not disappointed. In particular the first film of three, Rituaes e festas Borôro (Rituals and Festivals of the Borôro) (Brazil 1916) was one of the highlights of the festival. The filmmaker was Luiz Thomas Reis, photographer and cinematographer with the Commission of Strategic Telegraph Lines from the Mato Grosso to the Amazon, more simply known as the Rondon Commission. The Commission was tasked with mapping the unknown regions of Brazil and making contact with remote tribes. Reis documented this work on film, in part with the hope that the exhibition of such films would raise further funding.

Rituaes e festas Borôro is an extraordinary work, simply by letting the extraordinary speak for itself. Its subject is the Borôro people of the Mato Grosso region, specifically the funeral ceremonies for an elder of the village. I am no expert in anthropology, but the film seemed to me notable for its observant, unpatronising, humane manner. The camera never intruded, only witnessed, and the Borôro were not looked upon as objects of curiosity but as people respected for their customary practices and milieu. This was somewhat charmingly exemplified by the dogs. Stray dogs in early films are something of a Bioscope fetish, and Reis’ film captured not just the dances of the Borôro but the dogs who casually wandered in and out of the frame, surveying the strange things that these humans do in whatever part of the globe that humans happen to gather. The only questionable note was the assurance made by the film’s titles that these rites were not permitted to be seen by whites or women – yet here was the camera filming them. Such are the paradoxes of the anthropological film, a subject to which the Giornate would find itself returning in subsequent days.

Two other Reis films made for the Rondon Commission followed, Parima, fronteiras do Brasil (Brazil 1927) and Viagem ao Roroima (Brazil 1927). Each just under 30mins in length, these were more conventionally ‘travelogue’ in style. The first documented an inspection of the Brazilian-French Guiana border, following the river, with some thrilling shots taken from the front of a travelling canoe (the Brazilian version of the phantom ride), but with plenty of signs of encroaching colonisation in the builings that littered the banks of the river. The second explored the borderland between Brazil, Venezuela and British Guiana and concluded with breathtaking views of 1,000-foot high rock faces. In both films there were sequences where they came upon tribes, so positioned in the film as to be the big pay-off shots, the exotic conclusions which would capture the interest and wallets of likely funders. Rituaes e festas Borôro was in every sense the better film.

Mutter Krausens Fahrt ins Glück, with a band in the understage area playing the Internationale

So that was the morning session. A foul snack lunch and earnest conversations about budget cuts (again) and we were back at 14:30 for Mutter Krausens Fahrt ins Glück (Mother Krause’s Journey to Happiness) (Germany 1929). This was being shown as pat of the Giornate’s ‘The Canon Revisited’ strand. There is an occasional air of pompousness about the festival, and this idea of re-assessing canonical films exemplifies it. It’s a good idea to revisit classics, especially for the new audiences the festival is attracting, but a number of these films were titles that many of us had not had any chance to see the first time round; indeed I suspect most of us had not even heard of them. Mutter Krausens Fahrt ins Glück was a case in point; a film I’d vaguely heard of, but never seen, though I will admit it’s a classic of sorts and certainly merits being brought back to the screen once more.

Mutter Krausens Fahrt ins Glück is as agit-prop a film as you could expect to see. Directed by Piel Jutzi, it combines melodrama with documentary realism in its depiction of the ground-down lives of the Berlin proletariat. It tells of the family and tenants of an apartment managed by the aged Mother Krause (Alexandra Schmidt), pitting the apathy and resignation of the individualised poor (generally the elderly) against the positive binding together of those who follow the Communist party (generally the young). Its highpoint is where the harassed daughter (Ilse Trautschold) joins her boyfriend in a protest march to the sounds of the Internationale – literally so in our case, because at this point a marching band of red-suited musicians entered the Verdi theatre and played the marching song to much applause. It was a wonderful thearical coup – typical of the imagination that goes into the Giornate.

However, despite such rousing gestures, the film’s message was an unsettling one. We were supposed to reject Mother Krause’s miserablist view of her fate, but only after the film had done all it could to make us feel sorry for her, so that the ending – where she gasses herself and a sleeping child, because life simply isn’t worth it for either of them – was distasteful and the conclusion ambiguous. It was a stylish and imaginatively experimental film, but what it expounded was more posture than principle.

Next up came a selection of Pathé short comedies with surprisingly sophisticated live musical accompaniment from pupils of the Scuola Media “Balliana-Nievo” from nearby Sacile, music that was a good deal richer in colour and instrumentation than other schools’ work with silent films that I have heard. They were followed by pupils of Pordenone’s Scuola Media Centro Storico, who took on the truly bizarre Charley Bowers, an American comedian whose gimmick was to combine comedy with stop-frame animation. In There it is (USA 1928) he plays a Scottish detective from Scotland Yard who tackles the case of a haunted house with the aid of his cockroach sidekick, MacGregor. It wasn’t strictly funny, but it left this viewer – whose first Bowers film it was – opened-mouthed at its unabashed weirdness. If Salvador Dali had been employed by Leo McCarey, he might have made There it is.

In need of a break, I missed the new documentary Palace of Silents (USA 2010) on the story of Los Angeles’ Silent Movie Theater, returning for the evening’s screenings. The Giornate was celebrating the 75th anniversary of two of the world’s leading film archives, MOMA and the BFI National Archive. To mark its 75th year, the BFI took the interesting decision to try and recreate part of a programme of the Film Society. The Film Society was formed in London in 1925 by a bunch of radicals led by the Hon. Ivor Montagu, which eventually included such notables as Anthony Asquith, Iris Barry, Sidney Bernstein, Roger Fry, Julian Huxley, Augustus John, Bernard Shaw and H.G. Wells. The Society (the first of its kind in the world) put on films of artistic, historic or political interest at the New Gallery Kinema in Regent Street, often showing films from the USSR which had been refused a licence by the British Board of Film Censorship (they could do so because the films were shown to members of a private club). The Film Society had a huge influence on British film culture, and after it ceased operating in 1939 its collection went to the BFI.

On 10 November 1929 the members of the Society witnessed perhaps the most remarkable film programming coup ever – the world premiere of John Grierson’s Drifters, the cornerstone of the British documentary movement, and the UK premiere of Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, plus James Sibley Watson’s avant garde classic The Fall of the House of Usher (USA 1928) and Walt Disney’s Barn Dance (USA 1929). Now that’s programming.

Drifters (1929)

Audiences were made of sterner stuff in 1929, because we were only shown the first two. Drifters (UK 1929) is one of those classics more cited than seen and those who have seen it generally did years ago. Looking at it again after twenty years in my case, it is a work that easily merits its high reputation. It documents the work herring fishermen, and by its Soviet-inspired use of montage combined with a very British tatse for understated realism it immediately stands out from any other film of actuality produced in the UK (or anywhere else) to that date. One understands why its effect on audiences at the time was so electric, and why it did indeed inspire a whole school of documentary filmmaking.

However, it is also an odd film. It falls into three parts. The first, where the fishermen go out to sea, is in classic documentary style, showing man pitted against the elements, elevated (but not excessively ennobled) by toil. Part two, the night-time sequence, is strange. The fishermen sleep, but in the seas beneath we see the herring shoals swimming to and fro, menaced by dogfish. What has this to do with documentary? It tells us nothing of the people involved. Are we mean to gain insight into the lives of the fish? What is going on? It’s a sequence that dosn’t seem to get discussed much in studies of Drifters, yet here is the archetypal Griersonian documentary, and at its heart it slips into a strange, blue-tinted reverie, a fisherman’s dream. Part three is where the catch is taken to harbour, with often exhilaratingly scenes of commerce, industrialisation and human interaction. As Russell Merritt notes in the Giornate catalogue, “Grierson claimed the sequence was pointed social critique, exposing capital’s exploitation of the workers”. It is no such thing. It is unabashed championing of the power of the marketplace. Grierson the instinctive filmmaker was not the political filmmaker that he thought that he should be – he was too good for that.

Do you really need my thoughts on Bronenosets Potemkin (Battleship Potemkin) (USSR 1925)? As probably the most discussed film in history outside of Citizen Kane, I guess not. It was an odd way of celebrating the anniversary of the BFI National Archive, especially as the print came from the Deutsche Kinemathek, but it was enriching to compare and contrast with Drifters. It’s a film that disappointed me greatly when I first saw it (with the original Edmund Meisel score), probably because I was so expecting to be impressed and because of the absence of conventional narrative. As a story, it hasn’t got much going for it. As cinematic posturing, particularly as one of a planned series of films celebrating the 1905 revolution, it makes absolute sense. Every scene is overplayed, but it is always compelling to watch. There is not a dull composition in it.

And that was enough for a Sunday. I did see the first twenty minutes or so of Dmitri Buchowetski’s Karusellen (Sweden 1923), which looked fabulous. but I was sceptical of any story where a circus sharpshooter somehow is able to afford a vast country house and where the happily married wife instantly falls for a stranger because that’s what always happens with strangers. Enough of such artificiality – give me the kine-truth of documentary, and better still the unvarnished simplicity of actuality. For all of the canonical classics on show, the film of the day was a plain record of tribal dances from the Amazonian forest in 1916. So often the simplest is best.

Pordenone diary 2010 – day one

Pordenone diary 2010 – day three

Pordenone diary 2010 – day four

Pordenone diary 2010 – day five

Pordenone diary 2010 – day six

Pordenone diary 2010 – day seven

Pordenone diary 2010 – day eight