A fool there was and he made his prayer

(Even as you or I!)

To a rag and a bone and a hank of hair,

(We called her the woman who did not care),

But the fool he called her his lady fair –

(Even as you or I!)

Rudyard Kipling’s 1897 poem The Vampire (said to have been inspired by a painting of the same name by Philip Burne-Jones) has been hugely influential. It took a piece of Eastern European folklore which had had been popularised in Victorian literature and applied it to a new kind of woman whose sexual adventurous caused alarm and thrill in equal measure. The vampire came to films in 1913 with Robert Vignola’s The Vampire, starring Alice Hollister, but it was A Fool There Was (1915), which took its name from the first line of Kipling’s poem (by way of a play by Porter Emerson Browne), that stamped the idea of the vamp (and then the verb to vamp) on the consciousness of a generation.

The star of A Fool There Was was Theda Bara, and in her wake followed a number of screen vamps, each driving men mad and giving not a damn. Among them were Valeska Suratt, Olga Petrova, Musidora, Pola Negri, Helen Gardner, Louise Glaum, Dagmar Godowsky and Virginia Pearson. Lesser known than some of these, yet with perhaps a greater cult, is Nita Naldi, now the subject of a new website, Nita Naldi, Silent Vamp.

She was born Mary Dooley in Harlem, New York in 1894, into a “solidly blue collar, devoutly Catholic, and upwardly mobile” family. The family hit hard times, and Mary took to the stage, developing an exotic persona (Spanish or Italian according to whim). She took her name name from actress Maria Rosa Naldi, who she described as her sister for many years thereafter. She developed her vamp persona in assorted variety shows, including working for Florenz Ziegfeld. She got her first named screen role in 1920 in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, worked hard for a time for both screen and stage as she built up her name, then got her big break playing opposite Rudolph Valentino in Blood and Sand (1922). As the Nita Naldi site says, in its characteristically keen style:

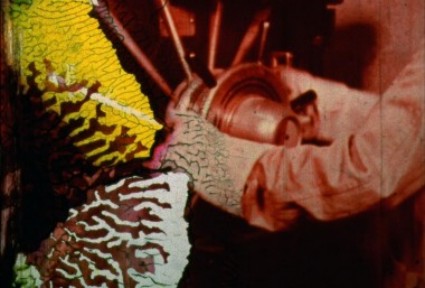

Nita, cast as fire-breathing man-eater Doña Sol, executes her signature role with a gleam in her eye and all the gusto she can muster. She swans about in outré ensembles, ogles Valentino and every other male in the film suggestively, wears a series of harebrained hats (one, a favorite here at Naldi HQ, is festooned with grapes), yawns as her victim dramatically perishes in front of her, and generally refuses to behave. It was not a role for Lillian Gish – but it suited Nita down to the ground.

Paramount awarded her a five-year contract and several nondescript titles followed (Anna Ascends, You Can’t Fool Your Wife, Lawful Larceny, Glimpses of the Moon, Don’t Call it Love, and The Breaking Point). She starred opposite Valentino again in A Sainted Devil and Cobra, but her star was on the wane, chiefly it seems because of a weight problem, though stories of heavy drinking and unclear sexuality probably didn’t help matters. As with many American stars on the way down, she sought work in Europe, and one of her last film roles was to play a non-vampish schoolteacher in Alfred Hitchcock’s lost film The Mountain Eagle (1925). She returned to the stage, married a wealthy man who promptly lost all his money in the Depression, soldiered on after his death maintaining the social life of a one-time film star, and died in straitened circumstances in 1961.

Nita Naldi, from ‘The Viewpoints of a Vamp’, Picture Show, December 1, 1923

It’s a not untypical tale of a screen performer’s rise and fall, but what makes Nita Naldi such an interesting, and now cultish figure is her intelligence, wit, style and devil-may-care attitude to life. She vamped on-screen and she vamped off-screen. Two of her fervent acolytes, Donna L. Hill and Joan Myers, members of the splendidly named ‘Daughters of Naldi’, plus auxiliary ‘daughter’ Christopher S. Connelly, have produced this excellent tribute site. It comprises a full biography, photo-gallery (divided up by film), ephemera section (photoplay books, articles etc.), filmography, stageography, a handy guide to vamping (Lesson 1: Lure the victim; Lesson 2: Assume the position; Lesson 3: Bite! Truly, Madly, Deeply!; Lesson 4: Celebrate!) and a Nita Naldi Cocktail.

Some of the exceptional material here is quite well hidden. The Daughters of Naldi have taken particular care over researching biographical material, including lengthy trawls through censuses, shipping records, naturalisation records and the like, and wherever US public domain laws allow, they have made available copies of the original documents in their notes and references section, with hyperlinks to PDFs. Similarly the articles, filmography and stageography sections have a number of valuable documents available in PDF format. Just look out for the hyperlinks.

Nita Naldi, Silent Vamp demonstrates that film history research can and should be fun. The research has been rigorous but the style is knowingly playful. More material is promised, including essays, more photographs and more biographical information – because many questions remain and the search must go on.

Well done to all concerned.