http://beta.bfi.org.uk

If someone offered you £25M to save the nation’s moving image heritage, what would you say, and how would you spend it?

Both questions are worth considering, because the first answer is that you couldn’t save the nation’s moving image heritage with ten times that amount, so you need more. In fact, when the UK’s public sector moving archives (excluding Scotland and Wales) were offered round about this sum four years ago from the Department of Culture, Media and Sport, it was less than they had originally asked for. The pitch had been for twice that amount, but funders love to give you just that little bit less than you asked for and see how well you do with that.

So you’ve got less than you hoped, and now you have to spend it. Of course you have to spend it against an argument presented to your funder, the argument here being a strategy in support of the UK’s screen heritage, which would help stabilise an unsteady and certainly underfunded sector. There were four ‘investment’ aims” to the strategy:

- Securing the National Collection

Capital works to extend and improve BFI storage facilities with appropriate conditions to safeguard the collection.

- Revitalising the Regions

Nomination of key collections in the English Regions, leading to improved plans for their preservation and access.

- Delivering Digital Access

Extending online access to the Nation’s screen heritage, through collection cross-searching and digitisation.

- Demonstrating Educational Value

Identifying, developing and evaluating effective use of screen heritage material within learning environments.

Four years on, and ‘demonstrating educational value’ rather got lost in the mix, but significant achievements have been made under the main three categories, and yesterday at the BFI Southbank they were announced to an invited audience. The Bioscope (naturally) was there.

It was a curious evening, which began with a clip shown from David Lean’s own 70mm print of Lawrence of Arabia, inelegantly cut off just as it was getting interesting, then effusive words in praise of film as a medium to inspire, move, inform, entertain, engage and so on. The main business, however, said little about the feature film and focussed chiefly on amateur and documentary film, stressing their special capacity for capturing human experience and strongly suggesting that the film history we have is a greatly inadequate one. We know a lot about a few films, said speaker Frank Gray of Screen Archive South East, and know next to nothing about a huge number of other films that lie in archives, demanding discovery, interpretation and sharing.

We heard from the people at the BFI who have steered the strategy, with head of collection and information Ruth Kelly doing a fine turn explaining the necessities of film preservation and even managing to make database management sound interesting. A panel session stressed the great value of archive film for an understanding of history and society, and the notable achievement of the strategy in getting so many film archives to work together for a common aim (how many other sectors could boast such co-operation?). The convenor, Francine Stock, suggested that what was being argued for archive film went a good way beyond nostalgia, but unfortunately we were then shown clips from the shamelessly nostalgic BBC series Reel History of Britain, first broadcast yesterday, which shows archive films being taken around the UK and projected to weeping audiences. Though it is always moving to see someone old see themselves when young, or a parent or grandparent when young, there is so much more to the medium than this. The series bombards you with the same emotional manipulation again and again. A wasted opportunity.

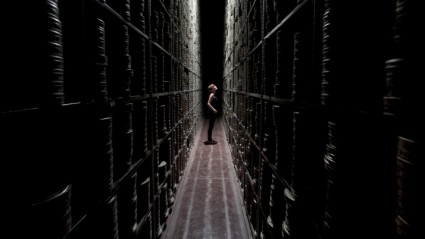

The BFI Master Film Store

But how did they spend the £25M (or £22.8M as it has boiled down to)? The greater proportion of it (£12M) went on building a new master film store for the BFI, though its facilities will be available for other archives as well. This is going to take the nation’s moving image heritage and keep it cold and dry (minus 5 degrees and 35% relative humidity, to be precise). As Ruth Kelly explained, a few years ago the BFI discovered that the traditional preservation model of copying from one film onto new stock was no longer sustainable, because the amount of films on the verge of deterioration was outstripping the resources available to manage it. The solution was to keep the films at a cold enough temperature to ensure that the process of decay was halted. You don’t copy, you freeze. It seems an obvious, economical solution now, but when first proposed it caused huge controversy, with the BFI attacked on all sides, and a secret online group formed to try and save the BFI from itself. How foolish that all seems now.

The master film store is being built at Gaydon in Warwickshire, and there’s a video guide to it on the BBC news site, with Ruth Kelly telling us the difference between nitrate, acetate and polyester, and showing us round.

Officially launched yesterday was another key output of the Screen Heritage Strategy, a union search facility enabling you to search across the databases of eleven film archives in one go. Entitled Search Your Film Archives, it has already been reported on by the Bioscope, and favourably. The idea is that the search mechanism will appear on the websites of each of the participating archives, so their users can find what’s held locally and nationally in the same place. It also links you to some 3,000 online videos on their websites of the respective archives. Search Your Film Archives is a good first step, and will get better in time. It is actually of huge significance as the potential platform for a new kind of national archive, one that is shared by partner institutions, who will eventually enjoy common preservation, digitisation, discovery and distribution services. This is what is interesting about Screen Heritage UK – it has seen that the answer to stablising film archives is to change the way they work, to change what an archive means. We are not there yet, certainly, but the desirable model is becoming clearer.

The Search Your Film Archives search facility on the London Screen Archives website, showing how users can either search across the LSA database or all databases

There will be more from the BFI on the database front soon. Their filmographic database is available online, but there is a separate technical database (known to its friends as TecRec) which tells you what materials they hold on each title. After years of trying, they have finally managed to marry up the two databases, which will be published as one under the name CID (Collections Information Database) very soon. It boasts an “innovative hierarchical data structure” based on the new European metadata standard for cinematographic works, CEN EN 15907. More on that when it appears.

And there there the regions. The UK has a number of film archives operating in the public sector. As well as the nationals (BFI, Scotland, Wales, Imperial War Museum) then are a number of archives representing the English regions, and having them work alongside the BFI through something like Search Your Film Archives or the Reel History of Britain TV series is wonderful to see. The regionals have each been pursuing their own Screen Heritage-funded projects, the outcomes of which will be announced in due course. As an example on the innovative approach to archive film being taken by such institutions, consider the Yorkshire Film Archive’s Memory Bank project, which is developing therapeutic uses for archive film footage in dementia, residential and domiciliary care settings. We’ll report on what has been achieved by these other archives with the Screen Heritage funds in another post.

Reel History of Britain is itself an outcome of the Screen Heritage project, though whether it is ‘revitalising the regions’ or ‘delivering digital access’ is not very clear. It’s putting films from the 1900s onwards onto the screen (that’s your token mention of silents in this post), under themes such as Evacuation, Teenagers, Slums, and Package Holidays. It features presenter Melvyn Bragg going about the UK in a mobile cinema and showing people films of themselves or their locality from the past. It revels in the coup of uncovering the descendants of people in archive films, delighting in the thrill of recognition, that tingle up the spine we get when we see that what the film depicts really happened and has its living connection with us today. It runs daily for 20 episodes, and some of the films featured just as clips will be shown in their entirety on the BFI’s Reel History site, which is a welcome innovation. If only a little more imagination and innovation had gone into the programmes themselves…

And, finally, there’s the BFI’s new digital delivery platform still in test mode, so it’s called BFI Beta, which is serving as the online to a lot of this activity. My, they have been busy.

So there’s an exciting future for film archives, but it’s really only a part of the picture for archives overall. Roly Keating, Director of Archive Content at the BBC, was on the panel last night. He pointed out that there had been a lot of talk about ‘film’, but that a screen heritage meant TV content too, and TV archives need to consider how they can likewise work together to enable greater care, discovery and sharing. But then he pointed out that moving images are just one digital object among many, and the real prize will be establishing shared systems in which films, books, images, manuscripts, sounds, websites, and anything else that contains knowledge can be found together. Some are already thinking along these lines (see Europeana or Trove, both covered by the Bioscope). The BBC is too, in most interesting ways. That’s where film belongs. The new film history is just history, with film in it.