I’ve turned the Questions section of this site into an FAQs (frequently asked questions). You can still post questions at the bottom of the page, but I’ve now added a range of general questions on silent film and using the Bioscope, which I’ll add to (and correct) as needed. Hope it’s useful.

Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers

The latest set of motion picture-related documents to be added to the Internet Archive by the Prelinger Library is the Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers. The SMPE (later the SMPTE i.e. Television was added to the name) was founded in 1916, and continues to this day as the “leading technical society for the motion imaging industry”. The Society’s journal, known know as SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal, also goes back to 1916, and the Prelinger team have so far digitised the annual volumes 1930-1954, plus a volumes of synopses of papers published 1916-1930. They will carry on up to 1962 (also they won’t be digitising the pre-1930 volumes as they don’t have a complete set).

There are numerous classic papers relating to the silent cinema period, and not just those published before 1930. The various volumes come with indexes to aid searching, but here are some noteworthy papers:

- Merritt Crawford, ‘Pioneer Experiment of Eugene Lauste in Recording Sound’, October 1931, Volume 17

- Oscar B. Depue, ‘My First Fifty Years in Motion Pictures’, December 1947, Volume 49

- W.K. Laurie Dickson, ‘A Brief History of the Kinetograph, the Kinetoscope and the Kineto-phonograph’, December 1933, Volume 21

- Carl Gregory, ‘Early History of Motion Picture Cameras for Film Wider than 35-mm’, January 1930, Volume 14

- Louis Lumière, ‘The Lumière cinematograph’, December 1936, Volume 27

- Robert W. Paul, ‘Kinematographic Experiences’, November 1936, Volume 27

- E. Kilburn Scott, ‘Career of L.A.A. LePrince’, July 1931, Volume 17

As usual, the individual volumes can be downloaded in DjVu, PDF and TXT formats.

Focus on Film

The Learning Curve is a free online teaching and learning resource provided by the UK’s National Archives (formerly, and far better known as, the Public Record Office). It brings together a range of archive materials around key historical themes, and this includes film. Its Onfilm resource has recently been revamped and renamed Focus on Film.

This now comes with 150 film clips, all of them downloadable and re-usable, and the site now has its own online editing tools, in The Editor’s Room. The National Archives does not hold film itself (selected British government films are preserved by the BFI National Archive on its behalf), so it uses film from Screen Archive South East, the BFI, the Imperial War Museum, British Pathe and the BBC.

There are several silent film clips available. There is an absolutely delightful film of Folkestone in 1904, with people just being themselves, parading up and down the streets, having fun at the beach, fooling before the camera, dressed on their Sunday best. It’s long been one of my desert island films (it has no known producer or title, and goes by the supplied title of Edwardian Folkestone), and I strongly recommend it (how drearily the teaching notes on the site describe it: “The roller coaster ride reminds us of the primary aim of early film-makers, profit via entertainment”). Scarcely less delightful nor more absorbing in its social detail is a 1920 tour through the streets of Canterbury, taken from the back of a moving vehicle.

There are newsreel films of the suffragettes, including the infamous film of the 1913 Epsom Derby in which Emily Davison runs on to the race-course and is killed. There are several film clips for the First World War, including key sequences from the great documentary testament The Battle of the Somme (1916). Somewhat peculiarly, there are also clips of a modern actor telling us about the experience of the Somme, which together with clips elsewhere of actors giving us vox pops on life in the Tudor and Stuart periods may end up confusing a few schoolchildren. There’s also footage from Ireland in 1916 (The Easter Rising) and 1920s.

The quality of the downloads is good (QuickTime Pro is needed if you are going to retain a copy), and the suggested activities (for PC or interactive whiteboard) and editing facilities are fascinating. Note that the site states: Teachers and students are granted a limited, non-exclusive licence to use the film clips for non-commercial educational use only and may not re-publish materials without permission of the copyright holder.

Well worth a look.

Now Playing

Now Playing is the title of a book and an exhibition on the hand-painted movie poster. The book is by Anthony Slide, Jane Burman Powell and Lori Goldman Berthelsen, and its full title is Now Playing: Hand-Painted Poster Art from the 1910s through the 1950s. The beautifully illustrated book cover the history of posters which were commissioned by individual cinema theatres and theatre chains, and celebrates the work of artists most of us have never heard of, such as Batiste Madalena, Ike Checketts, O.M. Wise and R.J. Rogers. There’s a really interesting interview with Slide, one of the most prolific and knowledgeable of silent film historians, on the Alternative Film Guide. Some amazing research has clearly gone into recovering a lost history of promotion and extraordinary artistic vision.

The book is complemented by an exhibition of original hand-painted movie posters at the Linwood Dunn Theater, at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ Pickford Center for Motion Picture Study in Hollywood. The exhibition is entitled Now Playing at the Dunn, and it looks gorgeous.

Journal of a Disappointed Man

Another diarist who died young. ‘W.N.P. Barbellion’ (1889-1919), whose real name was Bruce Frederick Cummings, published his diary under the title The Journal of a Disappointed Man in 1919, a few months before his death arising out of multiple sclerosis. The diary – philosophical, observant, raw – is considered a minor classic.

There is a Barbellionblog which reproduces Barbellion’s text in blog format. The diaries covers the period 1903-1917 and have a few references to cinema. On 15 March 1915 he makes the intriguing observation: “I felt the same sardonic humour as a cinema film provokes, showing you, say, the Houses of Parliament with a ‘fade-through’ of Guy Fawkes in the cellars underneath.”

But the most notable reference is that for 18 August 1907, when he was eighteen:

When I feel ill, cinema pictures of the circumstances of my death flit across my mind’s eye. I cannot prevent them. I consider the nature of the disease and all I said before I died — something heroic, of course!

This may be adolescent morbidity, but it is a haunting transference of the fear of death to the screen, suggesting how the idea of cinema played upon the imagination of the audience. It may also be an intriguing variation on the idea of life passing before your eyes at the point of death.

Neil Brand at Edinburgh

You can catch the indefatigable Neil Brand – pianist, composer, writer, actor, passionate advocate of the silent film – at the Edinburgh Festival this month, in two separate fringe shows.

Firstly, there’s The Silent Pianist Speaks, where Neil reveals the secrets of the profession of silent film pianist, acompanied by film clips. The show is running at the Pleasance Dome, Edinburgh daily until Monday August 27th.

If that wasn’t enough, there’s a staging of Neil’s original radio play, Joanna, performed the Invisible Theatre company, at the Jazz Bar. The blurb reads: “One grand piano. One secret. Joanna tells her tale of being encased in wood for a century, revealing more than just a few notes …”. There are tickets still available for the 17th, 18th and 19th.

Both shows have enthusiatic online reviews from audiences.

Diaries of a working man

As regular readers will know, I’m very interested in testimony of the film-going experience in the silent era. I’ve done a lot of research into the experience of cinema audiences in London before the First World War, using memoirs and oral history recordings, but what is really precious is original testimony from the time. For this, we have to turn to letters and diaries.

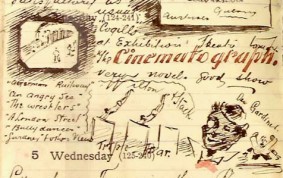

Needless to say, references to film and the cinema-going experience in these is hard to track down. But not impossible, and there are some precious examples to be found online. I’ll be posting assorted examples of these, as I find them, and I’ll start off with the diaries of Alexander Goodall (1874-1901). Goodall was a post office clerk in Western Australia, who died sadly young of tuberculosis. He kept up a diary from the age of seventeen, which he illustrated with delightful drawings as well as observant comments on the passing scene. The diaries are held by the State Library of Victoria, and have been published in facsimile form online by Pandora, Australia’s web archive.

Goodall took a sharp interest in the scientific developments of his day, and the diaries record his encounter with the Edison Kinetoscope (1 July 1895), the Edison Kinetophone – a combination of Kinetoscope peepshow and Phonograph music – which he calls the Phonoscope (2 July 1896) and the Cinematograph (3 May 1897).

To transcribe the short texts would be to spoil the visual effect. The picture above gives you some idea of the diaries, but you should follow the links to see them in their full glory.

More diaries in the near future.

A new claim

Another item from the Origins of Cinema in Asia conference, which took place in New Delhi last month. Stephen Bottomore wrote a short piece for the festival news letter, with a claim for what may well be the first exhibition of film to have taken place in India. Here’s his report:

Over the past twenty years I have been researching aspects of early cinema in libraries and archives in the UK and elsewhere. In preparation for the ‘Origins of Cinema in Asia’ conference, which took place over the past two days, I had a rummage through my unsorted material, and rediscovered an especially interesting article from the Journal of the Photographic Society of India of July 1896. In this article the editor tells us that, while projected cinema shows were by then an established fact, he had seen moving pictures of a different kind in India some months earlier:

‘I had an opportunity last cold weather of viewing Edison’s kinetescope [sic] in Calcutta. It was certainly extraordinary… But the pictures were too small, and the duration of the scene too short, to altogether satisfy me. Looking down through an object glass into a breast-high box one was first conscious of a whirring sound, then a sparking light, and presently a picture about 2” square appeared […] The scene was stirring enough in all conscience, and I gathered that it took a continuous chain or band of 1,400 celluloid positives to represent it. This band ran under an illuminated screen below which was an electric lamp – and to bring out the scene required a special camera invented by Edison.’ [He describes the film that he saw: a staged incident of a rescue of people from a fire.]

Although the writer does not mention the date when he saw this film in the peepshow Kinetoscope, he does state that it was, ‘last cold weather’, which would suggest the months at the turn of 1895 to 1896. Let us recall that the first film projection took place in India on 7 July 1896 at Watson’s Hotel in Bombay – indeed, this was the first film projection in Asia we believe. So this writer’s viewing of the Kinetoscope pre-dates India’s first film projection by several months, and therefore this is apparently the first appearance of moving pictures in India, and perhaps in Asia as a whole. (Although the Kinetoscope was seen in America, Europe and Australia in 1895, in Asia, apart from India, it was only introduced from later in 1896 – in Japan and Singapore).

Perhaps my historian colleagues in India – tireless researchers such as P.K. Nair – might already know about this appearance of the Kinetoscope in India in the winter of 1895/96. All I can say is that I have never seen this ‘first’ appearance mentioned in print histories of Indian cinema. And this suggests to me that many other important facts about early cinema in this region might remain undiscovered.

There is still much terra incognita when it comes to early film history, and still much to be learned about the dissemination of films and the means to exhibit them across the globe in the 1890s. The first film entrepreneurs saw the reach of their product in global terms – we as scholars should do so too. Certainly it would seem more work needs to be done to track the worldwide spread of the Edison Kinetoscope, to understand it as an international business phenomenon, and to pursue its many paths of influence.

The Silent Treatment

The Silent Treatment is an online newsletter isued in PDF format with news on silent cinema. Vol. 1 issue 3 is out now, for the August/September period, and includes news on screenings, festivals and discoveries, as well as reviews and other small items. Some stories you’ll have read in The Bioscope, many others are new, and each helpfully has its source cited. There’s no website for the four-page newsletter, which is a two-person operation, though one is planned. If you are interested in subscribing (it’s free), e-mail the editors at: tstnews – at – yahoo.com.

Update (March 2008):

There is now a website for The Silent Treatment, though to obtain the PDFs you still have to email them to join the subscription list.

Robin Hood and Der Rosenkavalier

News of two UK screenings coming which are worth nothing.

Firstly, 7 October 2007 sees a screening of the Douglas Fairbanks classic Robin Hood (1922) at the Royal Centre, Nottingham. The score is by John Scott, who also conducts the Nottingham Philharmonic Orchestra. Here’s some of the blurb from the Royal Centre site:

If you’ve never seen a Silver Screen Silent Classic before then now’s your chance to sit back and enjoy this home-grown tale played to a new original orchestral score by the legendary John Scott. If you have then you’ll know just what a treat you are in for with this exciting evening out.

Robin Hood (1922) was the first motion picture ever to make a Hollywood premiere, and starred a swashbuckling Douglas Fairbanks in the title role. This epic adventure was based on the legendary tale of Nottingham’s greatest Medieval hero, and was the first production to present many of the elements of the legend that have become familiar to movie audiences in later versions. One of the most expensive movies of the 1920s, an entire 12th century village of Nottingham was constructed. Telling the classic story of Robin and his band of Outlaws, Fairbanks is an acrobatic champion of the oppressed, setting things right through swashbuckling feats and makes life miserable for Prince John and his cohorts, Sir Guy Gisbourne and the Sheriff of Nottingham and good ultimately triumphs over evil.

For over 30 years John Scott has established himself as one of the finest composers for film having scored over 60 films winning three Emmy Awards and numerous industry recognitions of his work. His major film credits include Greystoke, The Legend of Tarzan, Charlton Heston’s Antony and Cleopatra, The Deceivers with Pierce Brosnan, King Kong 2,The Long Duel with Yul Brynner, Shoot To Kill with Sidney Poitier and the Jacques Cousteau Re-Discovery Of The World TV series.

Next, a little further away, but already being advertised and something of a hot ticket, there’s Der Rosenkavalier (1926), at the Royal Philharmonic Hall, Liverpool, with Richard Strauss’ music, performed by the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, conducted by Frank Stroebel. The screening takes place 14 June 2008. The film, directed by Robert Weine is something quite unusual among silent films, as the blurb explains:

However well you know Richard Strauss’s opera Der Rosenkavalier, or even if you don’t know it at all, this will surprise and delight you. It’s not a film of the opera but music with pictures, an independent silent cinematic version made in 1926 by the pioneering director Robert Wiene (best-known for the ground-breaking The Cabinet of Dr Caligari). The scenario of Der Rosenkavalier (The Knight of the Rose) was written by Hofmannsthal, the opera’s librettist, and includes new scenes and flashbacks, with a major role for the Marschallin’s husband, unseen in the opera. The music, played by a live orchestra, was arranged by Strauss with additional material, some newly composed. Masterminded by Frank Strobel, artistic director of European Film Philharmonic Berlin and a specialist in arranging and conducting music for silent films, this newly restored print with reconstructed final reel comes to Liverpool for the British premiere of this entertaining and fascinating rediscovery, a unique event in the history of film and opera.

More details from the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic site.