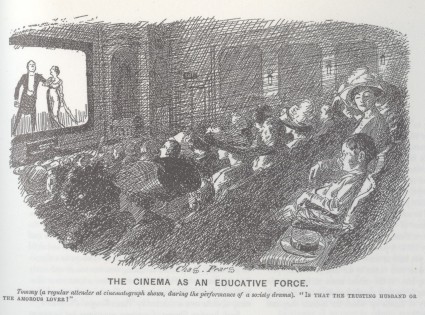

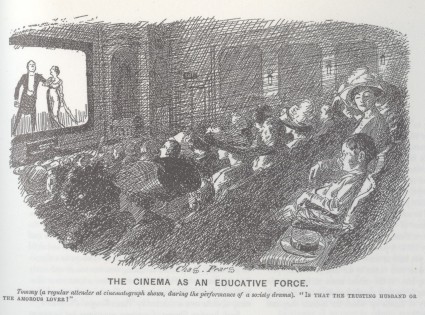

‘The Cinema as an Educative Force. Tommy (a regular attender at cinematograph shows, during the performance of a society drama). “Is that the trusting husband or the amorous lover?”‘ Charles Pears cartoon in Punch, 7 August 1912, from I Want to See This Annie Mattygraph

One of the most interesting ways to examine contemporary perceptions of the silent cinema is through cartoons – newspaper cartoons, that is, rather than animated cartoons. Cartoons in the popular newspapers, comics and magazines of the day provide a marvellous measure of how the new phenomenon of cinema was commonly understood, since cartoons had to tap into a general feeling about the subject. Everyone had to be in on the joke for it to work. And more than simply recording popular sensibility, cartoons of the era pick up on changes in such aspects as technology and film-going habits, providing a valuable documentary record as well as a social history one.

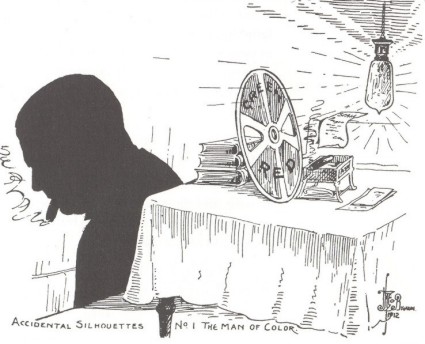

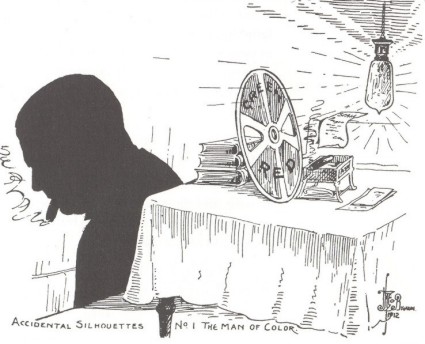

‘Accidental Silhouettes no. 1: The Man of Color’, a cartoon of Charles Urban by Theodore Brown, from The Bioscope 22 February 1912

The film trade papers of the day are another source of cartoons and caricatures, not always so polished or so funny, but often picking up on minutiae of film business concerns which are of value to the specialists, or simply providing the only portraits we have of some of the film personalities (i.e. those behind the camera) that we have. Theodore Brown, editor of the British journal The Kinematograph and Lantern Weekly, unusually was also an occasional cartoonist (and a filmmaker, and an inventor), and provided the above cartoon of film producer Charles Urban, shown silhouetted via a Kinemacolor filter, which regulars will recognise provides my avatar in the comments to posts on this blog.

Cartoons on silent cinema are scattered all over the place, and tracking them down can be a laborious business – more often than not the research stumbles across them by chance, or else works their way through the well-thumbed pages of Punch, which never fails to come up with the goods of some sort. There is, however, one book – and a very good book – on the subject, Stephen Bottomore’s I Want to See This Annie Mattygraph: A Cartoon History of the Coming of the Movies (1995). It must be said that the mixture of ungainly title and bi-lingual text (English/Italian) has not helped the book’s acceptance outside the hardy band of early film buffs. (The phrase that gives the book its title comes from a cartoon where a man asks at a box office if he can see what he assumes is an actress but of course the Animatograph projector – how they laughed in 1897). But within lies a rich selection of contemporary cartoons from across Europe and America, arranged around such themes as ‘Going to the Pictures’, ‘Opposition and Rgulation’ and ‘Film Genres’, providing a history of the cinema to 1915 through the pictures that made people at the time laugh about it. It is scholarly, observant and great to look at. I particularly value it for the cartoons of cinema-going, where you find evidence of exhibition practice and audience habits that really aren’t recorded elsewhere. Its opening essay also provides a valuable history of the cartoon over and above its relationship to film history.

But what can you find online? Not a lot, unfortunately, but one worthwhile source to direct you to is the British Cartoon Archive. This is based at the University of Kent at Canterbury, and is effectively the national collection of cartoons. Navigation on the site is a little unclear, but persevere and you’ll eventually find its database, which provides access to 120,000 cartoons, each illustrated with thumbnail image (click on the image for a larger view) and accompanied by exemplary cataloguing information, including an exhaustive array of thesaurus terms, the names of all real people featured in the cartoon, and transcriptions of the text.

Sample database search result with cartoons by W.K. Haselden, Sidney ‘George’ Strube and David Low

The Archive is rightly particular about protecting copyright images, so no reproductions here bar the web page picture grab above. But type in terms like ‘film’, ‘cinema’ etc and you’ll find such telling cartoons as W.K. Haselden’s ‘The all-conquering cinema’s advance’ (1924), where cinema screens crop up everywhere you look (even at Stonehenge), or David Low’s ‘Continuous show now on’ (1926) which comments on the beleaguered state of the mediocre British film industry, unable to compete against the block-booking Americans, while the overpowering attractions of an American vamp obscure those of the ‘pure but dull British film heroine’.

There are only so many cartoons there on the silent era, but more than enough to pick up on the social perceptions of the time. Look out too for David Low’s ‘Topical Budget’, a cartoon news commentary series which took its name from a popular newsreel of the silent era. There’s a lot more to explore on the British Cartoon Archive site, in particular a collection of biographies of the cartoonists.

There are other, far smaller sites out there marketing mostly Punch cartoons, but nothing that I can see that provides the opportunity to look at early cinema subjects. The various newspapers that have been digitised tend to be of the broadsheet variety, which did not stoop to such things at this time. The British Library provides a useful overview of comics from the era, such as Ally Sloper’s Half-Holiday and Comic Cuts, as well as titles like Film Fun, which began in 1920 and was entirely given over to comic strips featuring popular film stars. Other sites and databases offer just an image or two, provide descriptive lists of what they have but no images, or else a subscription is required. Or they don’t cover early cinema, of course. For a good listing of sites worldwide, go to the Intute: Art and Humanities site (an excellent UK academic service describing online scholarly resources) and type in ‘cartoons’.

Finally, it’s worth noting that a number of cartoonists of the era went on to become filmmakers. Among the best-known are Emile Cohl, Winsor McCay (‘Little Nemo’) and Harry Furniss. Cartoonists were filmed by the early filmmakers, often doing ‘lightning sketches’ (speedy drawings over a preparatory sketch), such as Tom Merry, J. Stuart Blackton and several British artists who contributed political sketches to proto-cartoon films during the First World War. The Library of Congress’ American Memory site includes Origins of American Animation, which demonstrates the interrelationship between paper and screen cartoons 1900-1921.

If anyone knows of other online sources for newspaper and comic journal cartoons which cover our period, do say.