G.A. Smith (the filmmaker) and his wife Laura Bayley in A Kiss in the Tunnel (1899)

The huge growth in geneaology on the web in the past few years has also provided a wealth of resources for the film historian. This post is based on a talk I gave a couple of years ago at the British Silent Cinema festival, and provides a guide to the sorts of resources available (particularly but not exclusively British sources) and what the film historian may gain from them.

1901 census

There have been ten-yearly censuses in Britain since 1801, though until 1841 they did not record details of individuals. It was the launch of the 1901 census online in 2002 that helped generate the explosion of interest in family history, though the National Archives were not expecting the millions who tried to access the site on its publication, which led to its immediate crash and an awkward gap of several months before it was resilient enough to be published again.

The census is available at www.1901census.nationalarchives.gov.uk [update: the link is now www.1901censusonline.com]. The records will provide you with the name, age, place of birth, the county and parish where the census was taken, and the person’s occupation. Hence, type in ‘Cecil Hepworth’ and you will get two results:

Cecil Hepworth / 9 / Lancs Manchester / Chester / Macclesfield /

Cecil Hepworth / 27 / Lewisham / London / Streatham / Cinematographer

One is clearly a British film pioneer, the other a blameless child. You can then view the census record (image of the original form plus a transcription), which will give you all of those resident in Cecil Hepworth’s houshold on the day of the census. For this you need to pay, for which they have a credits system. 500 credits cost £5.00 and are valid for seven days. Viewing a single image takes up 75 credits.

If you are looking for an individual with an unusual name, locating them is easy. A more common name will require a bit more preparation – an idea of age, location etc. Typing in Alfred Hitchcock gets you 66 records (he’s the one aged 1, born in Leytonstone), while Charles Chaplin yields 151 records (he’s the one aged 12, living in Lambeth, occupation ‘Music Hall Artiste’). The full census record will tell you so much about who they lived with, their occupation, social status, and ultimately their ancestry.

Using the Advanced Search option is potentially very interesting, but also frustrating. It ought to be possible to search for everyone in 1901 who was working as a cinematographer, but to do so you have to enter at least two letters with wildcard (e.g. AB*) into the name field at the same time, so to trace everyone who might be a cinematographer in the 1901 census in theory would take 650 individual searches (in practice a lot of letter combinations could be rejected of course). Someone with the patience to do that is the film historian Stephen Bottomore, who conducted a search for profession beginning ‘cine*’, and found a remarkable list of names, most of whom are unknown to film history as yet. Here’s a selection (with transcription errors):

Name / Age / Where Born / Administrative County & Civil Parish / Occupation

Alvey, Harry / 19 / Notts Nottingham / Lancaster West Derby / Cinematograph Operater

Banford, George / 20 / London Hornsey / London Islington / Cinematic Image Maker

Barton, Benjamine / 40 / Warwick Birmingham / Birkenhead Birkenhead / Cinematographer Ethil

Bayliss, Thomas / 51 / Staffs Bradley / Leicestershire Measham / Cinematographic Artist

Brecksapp, Thomas / 27 / Brixton London / Sussex Hove / Cinematographer

Bromhead, Alfred / 24 / Hampshire Southsea / Surrey Kent / Penge London / Cinematograph Agent

Catlin, Edwin / 43 / London St Pancras / London Islington / Cinematograph Operator

Chadwick, Julia / 25 / Lanc Rochdale / Lancaster Rochdale / Cinematograph Operator

Clarke, Herbert / 27 / London St Pancras / London St Pancras / Cinematograph Proprietor

Cramer, Horace / 23 / Sussex Hastings / London Paddington / Cinematograph Operator

Croft, Emelina / 27 / Weybridge Surrey / Surrey Weybridge / Cinemelographer

Davey, Frederick / 20 / Surrey Croydon / Borough Of Oxford Cowley St John / Cinematsgraph Operator

Just the one well-known name there – Alfred Bromhead, who went on to run the Gaumont company in Britain. And astonishing to see two women cinematograph operators (which could be camera operators or projectionists or both). Stephen has kindly made his whole list available as a PDF. Do note that film people got described under a variety of terms – bioscope operator, photographer etc. – so Stephen’s list is just a start. The census gets released to the public one hundred years after it was made – 2011 is going to be quite a year for British film history research.

Update (January 2009): The 1911 census is now available online, published ahead of its centenary owing to an anomaly in the 1920 Census Act. Information on using it for film history research here.

http://www.ancestry.co.uk

Ancestry and FreeBMD

The 1901 census is a good place to start, but for a proper study of British, and international, records, you need FreeBMD and Ancestry. FreeBMD is one of those marvellous resources which the web has encouraged and pure human goodwill has sustained. It is a transcription of the Civil Registration index of births, marriages and deaths in the UK from 1837 to around 1900, and will eventually be complemented by free resources for census and parish register data. It’s all put together by volunteers, and though not quite finished yet it is an indispensible resource, which allows you to search across British births, marriages, deaths, or all three, assorted combinations of name, dates ranges, location etc. It won’t lead you to the documents themselves, and it helps to know a little about how civil registration data is organised to get the best out of it, but it is first-rate research tool.

And then there is Ancestry. Ancestry.co.uk and Ancestry.com are the big players in worldwide genealogy online. Here you will find births, marriages and deaths records for the UK 1837-c.1900, all UK census records 1841-1901 with digitised images of the census forms, local directories (including phone directories), US federal census data going back to 1820, some individual American states’ birth, marriage, divorce, death, military and census records, and much much more. Ancestry is continually adding new resources, and also links name searches to online family trees.

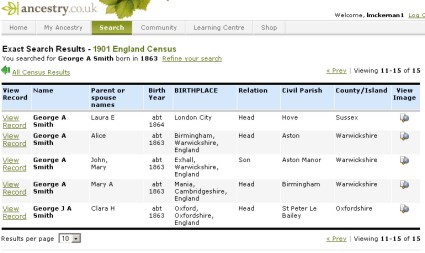

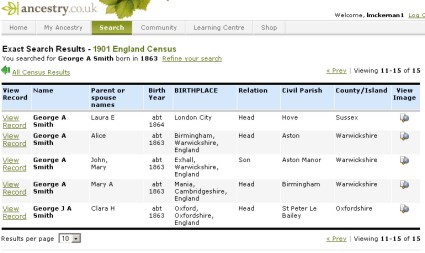

Most of this is not free. There is a variety of subscription options, on a pay-per-view basis, monthly, or annually, and either worldwide or restricted to your country. But for a few pounds a month (a monthly UK membership is £9.95) you can have access to every census record 1841-1901, and there are such marvellous things you can find. So, for example, I can trace Charles Urban – a particular interest of mine – aged 13, living in Cincinnati, in the 1880 US Federal census (freely available), through to the 1901 British census, where he is in London, aged 34, and described as ‘Manager Animated Pictures’. But beware! Ancestry’s transcriptions of census data are notoriously riddled with errors, and you have to be prepared to think laterally and to search under mispellings and the like. You won’t find Charles Urban in 1901 by searching on his name – it’s been mis-transcribed as Verban. As ever, it’s harder looking for common names. The frame grab from Ancestry above is the 1901 record for George Albert Smith, who I eventually found under George A. Smith, identifiable by his age, wife’s name (Laura) and location, Hove.

Other resources

Many people start out looking for family history information with the International Genealogical Index (IGI) or FamilySearch.org. This is the mind-boggling attempt by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (i.e. the Mormons) to create a register of all births, marriages and deaths, worldwide, as far as they possibly can, with the underlying intention of baptising anyone who might be their ancestors into their faith. The result is a directory of millions of names, taken from parish registers, census records, social sectority death records etc, plus information supplied by individual researchers. It is not primary source information, it is riddled with errors or dubious interpretations, and should only be used with caution, a pointer as to where to look next. For the film historian, it should not be the first point of call.

These are some other key genealogy resources not yet mentioned:

Genuki – a reference library of genealogical information for the UK and Ireland.

RootsWeb – a worldwide genealogical ‘community’ – a good place for posting questions about family names you may be researching.

Genes Reunited – family history based on the Friends Reunited principle, where the more people who join in and add data, the more comprehensive the resource.

ScotlandsPeople – the official source for Scottish genealogical information, including births/marriages/deaths, census records, parish registers and wills.

Findmypast.com – previously known as 1837online, this is a commercial site which as well census and civil registration records has migration and military records, and offers access to the index of birth, marriage and death records up to the 2002, including overseas records. This is less wonderful than it sounds, as they offer you page records, or groups of page records only, rather than individual name records, and searching for an individual takes ages, and becomes expensive.

General Register Office – from here you can order copies of birth, marriage and death certificates in the UK. There are national equivalents around the world, a growing number of which provide online ordering of certificates.

http://www.ellisislandrecords.org

Passenger lists

And there’s more. Passenger list records are a key source for tracing film people sailing to different countries. Findmypast.com has co-operated with the National Archives to provide ancestorsonboard.com. This is a database of outward passenger lists for long-distance voyages leaving the British Isles from 1890 onwards. Eventually the resource will go up to 1960, and data up to the end of the 1930s has just been added. Name searching is free, but there is a charge for looking at the ships’ transcripts. As ever, it helps to be looking for a unusual name.

But the champion in this area is Ellis Island Records. This is a free resource free offering records of all those arriving at New York’s Ellis Island 1892-1924. This will give you the passenger details, where they came from and when they arrived in New York, plus the ship’s manifest (i.e. the full record of everyone travelling on that ship) as image or transcribed text. So you can not only get someone’s personal details, but who they were travelling with (family, friends, business associates), in what style (first class? steerage?), plus of course how often they travelled between Britain and America.

There is a whole lot more out there, and it can be a bit bewildering for the newcomer. As a guide through the maze of internet genealogy sources, the essential starting point is Cyndi’s List, which is the widely recognised leading sources of family history links, which is helpfully categorised by theme and country.

For reading, I recommend Peter Christian’s The Geneaologist’s Internet as a thorough and helpful guide through the thicket of online resources, what to expect from each one, their particular advantages and pitfalls.

There is a great deal that can be found in family history sources to benefit the film historian. Obviously if you are looking into the personal history of someone you are interested, these will be essential resources. But you can also learn about the social position of people in the film industry, their locality, mobility, business links, associates and self-image (Charles Urban calls himself ‘manager’ on some sources, on others he describes himself as ‘scientist’). Information from the records of one person will send you off researching other names that you hadn’t considered, and lateral use of the resources will open up new ways in which to examine film history. Who was Julia Chadwick, cinematograph operator from Rochdale, and Emelina Croft, cinematographer in Weybridge, Surrey? How did they get into the business? Who did they work with? What happened to them? The clues are there.