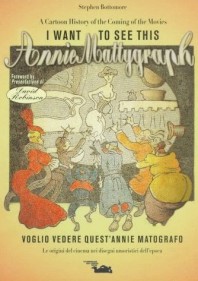

Just recently published in paperback, The Bioscope Man is a novel by Indrajit Hazra, which has its background the days of silent cinema in Calcutta. It tell of the rise and tragic fall of Abani Chatterjee in the 1920s Indian bioscope business, starting as projectionist’s assistant and ending up a star performer, only for ignominy and failure to follow. Other fiction and reality interestingly combine – among the characters in the book are Adela Quested (from E.M. Forster’s A Passage to India) and Fritz Lang, who comes to India to make a film starring Chatterjee but ends up producing Metropolis instead. As with many aspects of Hazra’s book, this has some some grounding in historical reality, as in 1921 Lang and wife Thea von Harbou scripted the two-part Das Indische Grabmal, directed by Joe May and set (but not filmed) in India, and Lang had a lifelong fascination with India. The word ‘bioscope’ was – and remains – a common term for cinema in India, and Hazra notes that the name came from Charles Urban, whose Bioscope cameras and projectors were used by the first Indian filmmakers and exhibitors.

I’ve not read the book yet, but reviews from the Indian press, though mixed, give an interesting flavour of its contents. The Hindustan Times points out the care taken over making the background film history convincing:

The Bioscope Man is set in the Calcutta of early 20th century However, echoes of what is happening on the other coast in Bombay keep intruding into the margins of the story of the rise and fall of his protagonist.

Two years after Dadasaheb Phalke made the first full length feature film in India, Raja Harishchandra, in 1917, a Bengali film, Bilwamangal, produced under the banner of Madan Theatres, was screened in Calcutta. Harishchandra S. Bharvadekhar, a still photographer and dealer in equipment in Bombay was the first to make a film (two, brief films, in fact) in India in the late 19th century. And not too long after, in 1901, Hiralal Sen set up Royal Bioscope in Calcutta to make films: he photographed dance sequences and scenes from plays being staged at Classic Theatres. (‘Bioscope’ is the name of an early film projector for splashing moving images on a screen. It became the generic name for cinema after the American Charles Urban – producer of the world’s first successful natural colour motion picture system, Kinemacolor, as Hazra mentions in his book – popularised it.)

Hazra, a journalist who happens to be a novelist (perhaps it is the other way round), uses his ferreting skills to take the reader behind the silent parde ke peeche, into the fairly cut-throat world of the early pioneers of silent movies in Calcutta.

He also situates his story against a vividly portrayed background of a city whose confidence is being undermined by the decision of the British to shift their capital to Delhi. In the background as well, but palpably present, are the repercussions of the first partition of Bengal – usually through the fringe characters who keep popping up in the novel and the stray remarks tossed occasionally.

While the author has woven many themes into the novel – a critique of Orientalism, a portrait of the Bengali bhadralok in Victorian India, self-deception, the birth and infancy of silent movies – it is the marvellously drawn portrait of the actor whose rapid rise and fall marks him. The actor’s reflections upon his life and work are riveting.

The review in The Newindpress on Sunday shows how the hero’s experiences in the Indian film industry resonate with wider concerns, while describing how Chatterjee meets his downfall:

He starts as a projectionist’s assistant at the Alochhaya Theatre, graduates into being a prompter, and by a lucky twist of fate ends up playing the title-character of Prahalad Parameshwar. He subsequently essays the roles of Othello, Ram, Parasuram and Shivaji, and his silent movies lead to resounding success. He starts getting recognised in street corners and quaint cafes, and is nothing short of being a star.

Hazra successfully experiments with technique, so we find three interludes interspersing the narrative like the titles of the silent films: the stylised stories of Prahalad, Anandhamath and the Black Hole of Calcutta. These bioscopes starring Abani are instant hits with the masses because of their daring portrayal of intimacy and undercurrents of nationalist chic. Yet, he views freedom fighters as “criminals with ambition” and maintains his nonchalance towards nationalism even as various upheavals rock the subcontinent.

Here, brown men (teeming with Bengali pride) share a love-hate relationship with mems: Abani chooses corrosive satire to attack the shape-shifting Annie Besant, though he initially finds her “American” and desirable; Shombu Mama is infatuated with bioscope diva Faith Cooper; and Abani labours under the weight of his undeclared, one-sided love for his onscreen sweetheart Felicia Miller.

On hearing the news of Felicia being shipped to Australia by her disapproving father, Abani enters a trajectory towards ruin when he mistakenly enters a ladies’ restroom. The man with the “bioscope in his bones” falls from grace and spends a decade playing minor roles.

A tart review from The Hindu also focusses on the wider historical background, indicating how the novel may end up being viewed quite differently by audiences within and outside India:

What is it with Indrajit Hazra? Why is he so hung up on the English? A good deal of the novel is a diatribe about the partition of Bengal in 1905 and the shifting of the capital from Calcutta to Delhi in 1911. He tells us about how disastrous it all was for the cultural life of the city and how everything went to seed after that. Curzon, Minto and Hardinge come in for a lot of stick, which is bad enough, but then he goes after old Winston. During a discussion about whether Charlie Chaplin should be called English or American, one of the animated Bengalis inhabiting this novel comes up with this argument: “No, no Shombhu-babu. That doesn’t make him American. Does the British Minister of Munitions become an American just because his mother is American? No, Lahiri babu, Churchill is English.”

There are references galore to period socio-economic gloom, period costume, period food, period politics. Which is all very well but the fact of the matter is that all this does not push the plot forward at all. The author has done huge research, pushed the story into the canopy , then tucked in the ends.

The Bioscope Man is a well-written book in the sense that there is no doubt about Hazra’s command over the language. It is the content one is worried about. Sometimes one wonders which nation he is writing for. In the beginning of the novel he talks about the eating of shingaras and jilipis. Shingaras are, of course, the samosas of Calcutta but take a look at his description of jilipis — “bearing a resemblance to miniature French horns fit for an orchestra of midgets.” No doubt Hazra’s European translators will have a lot of fun with that.

They will also have a lot of fun with the last quarter of the book in which Fritz Lang, German expressionist film maker, turns up in Calcutta to make a film starring Abani Chatterjee. The film is titled: “The Pandit and the Englishman” and is about Pandit Ramlochan Sharma, the Sanskrit tutor of the Orientatlist Sir William Jones. The film is made with great fanfare, but in 1927 the film that is released by the UFA Studio in Berlin is not Abani Chatterjee’s film, but Lang’s Metropolis.

The Bioscope Man is published in India, the UK and the USA. It is Indrajit Hazra’s third novel. Curiously, it is not the only novel set in the early Indian film business to be out at the moment. Tabish Khair’s much-praised Filming: A Love Story, just out in the UK in paperback, centres on 1940s Bombay cinema at the time of partition, but looks back to earlier modes of filmmaking (while echoing these in the novel’s style and framework).

Silent cinema in India has attracted increated critical interest in recent years. There was a major retrospective at the Pordenone Silent Film Festival in 1994, out of which came Suresh Chabria’s book, Light of Asia: Indian Silent Cinema 1912-1934, which includes a lenghty filmography. The major reference source in English is Ashish Rajadhyaksha and Paul Willemen’s monumental Encyclopedia of Indian Cinema. A leading Indian authority is historian P.K. Nair, who writes about the origins of Indian cinema on the Phalke Factory wiki (D.G. Phalke being the creator of India’s first feature film, as noted in The Bioscope Man).

Indian silent films on DVD remain a rarity, but the BFI has issued Franz Osten’s A Throw of Dice (1929), with music by Nitin Sawhney, which strictly speaking is an Anglo-German production, but was filmed in India and has been understandably claimed as an Indian film.

Finally, there was an article recently in The Hindustan Times on preserving India’s film heritage which sadly notes that only twenty-four of the many hundreds of films made in India during the silent era are known to have survived (three of them being films made by Franz Osten).