Neil Brand is a silent film pianist. That much is known by most enthusiasts for silent film in the UK, and by a good many around the world as well. It may not always be realised that Neil is also a writer, composer, actor and scholar, one whose prodigious energies and superabundant talent make him not far short of a national treasure. Hmm, why that note of qualification? – he is a national treasure. And now, as if accompanying silents live and on DVD, writing radio scripts and musical comedies, acting on film and TV, writing books and educating students were not enough, now he has turned online archivist with his latest venture, The Originals.

The Originals is a new section of Neil’s personal site which brings together original materials relating to the performance of music to film in the silent era. For some while now Neil has been collecting articles, scores, interviews, memoirs and eye-witness accounts which document the experience of seeing or performing to films in the 1910s and 1920s. He has now started to put some of this material online.

http://originals.neilbrand.com

The site is in three sections: Interviews, Archive and Memories. Interviews features a small collection (so far) of interviews and articles which give the point of view of musicians who were employed in cinemas during the silent era. These include a transcription of a 1988 interview with the 94–year-old Ella Mallett, former silent movie musician (carried out as part of the BECTU History Project which records interviews with veterans of the British film and television industries); an extract from Maurice Lindsay’s memoir of Glasgow life, As I Remember; an extract from New Zealander Henry Shirley’s memoir Just a Bloody Piano Player; and a highly evocative piece from novelist Ursula Bloom about her experiences as a teenage silent film pianist in St Albans (contributed by yours truly).

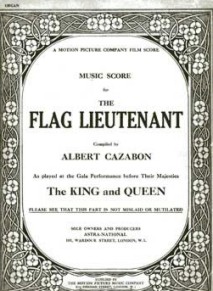

Archive is the section that is going to attract the most interest. This offers PDF copies of various original documents relating to silent film music, including extracts from original music that would have been performed with various films. The jewel here is selected pages from the score for The Flag Lieutenant, compiled by Albert Cazabon, and the only surviving full score for a British silent fiction film in existence. You’ll also find music for the Douglas Fairbanks picture The Black Pirate, an eyebrow-raisingly dismissive article on the profession of silent film pianist, cue sheets for Hell’s Heroes and The Hound of the Baskervilles, and more.

The third section, Memories, presents extracts from the 1927-1930 diaries of Gwen Berry, who played ‘cello in the orchestra pit of the Grand Cinema, Alum Rock Road, Saltley. The extracts, from 1929, show Gwen’s apprehension at the arrival of the “terrible talkie pictures” which were going to throw so many musicians such as her out of work. The diary is presented in a elegant turn-the-pages digital form, which does require that you install a plug-in for DNL ebook software.

All in all, The Originals is an excellent idea, and one that The Bioscope hopes will grow and grow, not least if those interested are able to send relevant materials to Neil so that they might be shared by all.

Meanwhile, here’s a handy survey of other things NeilBrandian…

- The Neil Brand website has biographical details, audio extracts from some of his live scores, an events calendar, news, reviews, a 2000 radio interview, and information on his score, publications and shows, including The Silent Pianist Speaks and his radio play Stan (on Laurel and Hardy).

- DVDs on which Neil’s playing and scores can be heard include The Gold Rush, South, The Life Story of David Lloyd George, Early Cinema – Primitives And Pioneers, Piccadilly, The Cat and the Canary, The Wrecker, The Open Road, Lobster Film’s Retour de Flamme series, Der Var Engang, Den flyvende Cirkus, Det hemmelighedsfulde X, Dickens before Sound and Ich möchte kein mann sein. Original scores not yet on DVD include Shooting Stars and Blackmail (full orchestral score premiered at Il Cinema Ritrovato, Bologna in 2009).

- Neil’s book Dramatic Notes: Foregrounding Music in the Dramatic Experience is a guide to how composers create music to support drama, whether in the form of film, theatre, opera, radio or TV, organised around interviews with such figures as Judith Weir, Barrington Pheloung and George Fenton.

- Neil is a visiting professor of the Royal College of Music.

- Neil is the accompanist for the Paul Merton’s Silent Clowns touring show, in which the TV comedian introduces silent comedy films to new audiences.

- Neil’s TV work is too extensive to list, but silent-related stuff includes Paul Merton’s Silent Clowns and Silent Britain.

- Neil is doing more and more on radio. He is a regular on Radio 4’s The Film Programme (where he analyses famous film scores), his radio play Stan (which was transferred to TV) tells of Oliver Hardy’s last days, while other work includes the plays Seeing it Through, Headliner and most recently the excellent comedy series about a surveillance team, Sneakiepeeks.

- And then there’s the musical theatre work – Neil has written music and lyrics for numerous shows. His current project is Talking with Mr Warner (as in Jack Warner, who gets captured by a disaffected musician on the opening night of The Jazz Singer…).

- Plus there’s regular appreances at the Giornate del Cinema Muto, British Silent Film Festival, Il Cinema Ritrovato, other festivals around the world, and many shows up and down the UK.

- Finally, Neil can be seen as an actor in Ken Loach’s The Wind that Shakes the Barley (he plays a silent film pianist) and he served time as the villainous Ted in the BBC TV series Switch, a soap opera for the deaf community, from which let me share with you this glorious image:

Bravo, Neil.