All frames from Zepped in this post come from http://www.independent.co.uk

Last week there was much publicity about the discovery of an apparently lost Charlie Chaplin film. Morace Park, of Henham in Essex, purchased a nitrate film from eBay for the princely sum of £3.20 ($5), though he was more interested in the can. When he opened the can he found a reel of nitrate film bearing the title Charlie Chaplin in Zepped. Park could find no record of the film in any Chaplin filmography or biography. The film was a mixture of live action film of Chaplin and animation. Park’s neighbour just happened to be John Dyer, a former member of the British Board of Film Classification, and together they began investigating the history of the film.

They have been thorough in their studies so far, and have determined that the film features unused footage from the Chaplin films The Tramp, His New Profession and A Jitney Elopement. The Independent newspaper, which carries the fullest account of the discovery (including several frame illustrations), describes the film thus:

The unearthed film, called Charlie Chaplin in Zepped, features footage of Zeppelins flying over England during the First World War, as well as some very early stop-motion animation, and unknown outtakes of Chaplin films from three Essanay pictures including The Tramp. These have all been cut together into a six-minute movie that Mr Park describes as “in support of the British First World War effort”. It begins with a logo from Keystone studios, which first signed Chaplin, and there follows a certification from the Egyptian censors dating the projection as being in December 1916. There are outtakes, longer shots and new angles from the films The Tramp, His New Profession and A Jitney Elopement.

The main, animated sequence of the film starts with Chaplin wishing that he could return to England from America and fight with the boys. He is taken on a flight through clouds before landing on a spire in England. The sequence also features a German sausage, from which pops the Kaiser. During the First World War there was some consternation that the actor did not join the war effort.

At first it seemed to those who thought they knew their Chaplin history, and the habits of film collectors, that this was some cobbled-together item by someone who had edited together Chaplin clips with a separate animation film of the 1914-18 period, Chaplin being a regular subject for animators at this time. But then evidence turned up that there had indeed been a film called Zepped, exhibited in Britain in 1916. In 2006 British film historian Mike Hammond had uncovered a reference to the film in a Manchester journal (probably Film Renter), as an article in a Russian online journal reveals (scroll down to note 43 and get an English translation through Babelfish).

So what is this peculiar hybrid? The six-minute film is a mixture of Keystone and Essanay titles, plus the animation. Chaplin left Keystone in 1914 to join Essanay, leaving the latter to join Mutual in 1916. Essanay is known to have tried to make the best out of its loss by issuing Triple Trouble (1918), a mish-mash of Chaplin outtakes, but Zepped contains Keystone and Essanay titles, suggesting a still more irregular arrangement. The existence of an Egyptian censors’ certificate only adds to the peculiarity of the whole affair. There seems to be a connection with the accusations made at the time that Chaplin was avoiding his military duty by residing in the United States, though clearly this was an unofficial film and Chaplin had nothing to do with its production.

Chaplin biographer Simon Louvish speculates (in the Independent article) that the film was compiled in Egypt, which was under British occupation at the time. However, no one was making animated films in Egypt in 1916. The access to the outtakes suggests an American source, yet the theme and reference to ‘Blighty’ in the title cards hints at a British source. The frames showing some of the animation (below) look like the crude semi-animated films that British artists such as Lancelot Speed or Dudley Buxton were making at this time. The reference to ‘Made in Germany’ is a British allusion (there were protests at the import of German goods into Britain long before the War), and America was scarcely indulging in anti-German propaganda at this time. I’d point the finger at a British film distributor.

The film has been transferred to DVD, and Park and Dwyer have been showing it to assorted Chaplin experts. They have also started making a documentary film in America about their voyage of discovery, and you can follow their ‘Lost Film Project’ through Twitter and through a project blog. They seem to be making a good job not only of exploiting the discovery but of seeking to understand it. If it’s not quite ‘THE cinematic find of the last 100 years’ that the blog claims, it’s a real coup – not least for how it has left the experts baffled. We now await anxiously for the results of their researches.

Update (20 November 2009):

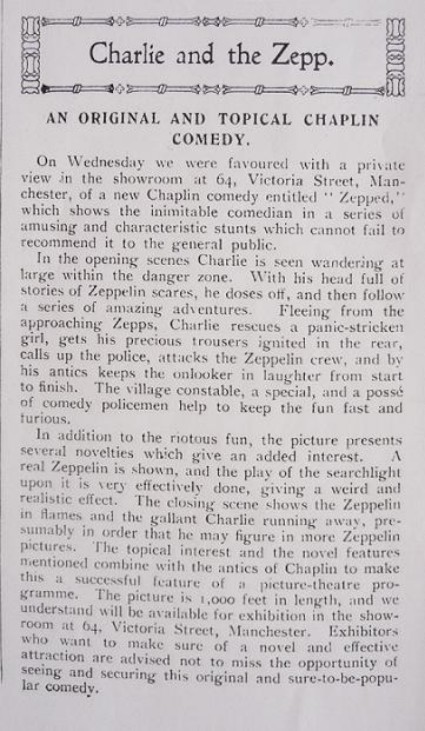

The people behind the Zepped discovery have kindly sent me two advertisements for the film plus a press notice, all from the journal Film Renter. Now we learn that the film was made by Screen Plays Co. of Manchester, that it was 1,000 feet long, and that there was some sensitivity over its relationship with Chaplin because the first version of the advert pointedly neglects to mention his name. He is mentioned in the second, however:

Original advertisment from Film Renter, 23 December 1916

Revised advertisement from Film Renter 30 December 1916

Press notice from Film Renter (date not given)

You can see the documents on the website for the company producing the documentary about Zepped, Clear Champion Ltd.

Another update (11 July 2011):

The latest extraordinary twist in the Zepped saga is that another print of the film has turned up, this time in a second-hand shop in South Shields, UK. This second Zepped is slightly incomplete (opening shots of a Zeppelin are missing, apparently) but otherwise looks to be the same film. It was discovered by one Brian Hann. More information (though with a muddled idea of the film’s history and value) is given in The Shields Gazette and in the comments below.

Brian Hann with the second Zepped, discovered in a South Shields second-hand shop