Albert Kahn, from http://www.ejumpcut.org © Albert Kahn Museum – Département of Hauts-de-Seine

A lot of people are coming to this blog in search of information on Albert Kahn, following the BBC4 series The Wonderful World of Albert Kahn. The Kahn collection is best known for its still photographs, which largely lie outside the concerns of The Bioscope, but he did employ motion picture cameramen too (as well as acquiring film from other collections), so here’s a short account of his Archives de la Planète, and some pointers on where to find out more.

Albert Kahn was a millionaire Parisian banker and philanthropist who decided to use his fortune to document the world in photographs. Between 1908 and 1931 he sent out still photographers and motion picture cameramen to create a photographic record of the globe. The project was supervised by geographer Jean Brunhes, who employed around eleven cameramen who visited forty-eight countries and brought back 72,000 Autochrome colour plates, 4,000 steroscopic views, and 600,000 feet of film. They also acquired film from commercial companies, including newsreels and scientific films. Kahn called the project the Archives de la Planète. Kahn lost his money in the Depression, bringing an end to the project, but the collection survived. It has remained remarkably little known, particularly the film component, but a steady trickle of academic interest in recent years has now been followed by the success of the BBC4 series, which has rightly startled people with the beauty of the images and the sheer extent of what they recorded.

Most of the film collection is in the form of unedited rushes of actuality subjects: everything from film taken in Mongolia in 1912-13, to the signing of the Briand-Kellogg Pact in 1928, A.J. Balfour visiting Zionist colonies in Palestine in 1925, fisheries in Newfoundland in 1922, and dancers in Cambodia in 1921. Kahn’s cameramen included Stephane Passet, Lucien Le Saint, Léon Busy, Frédéric Gadmer, Camille Sauvageot and Roger Dumas.

There is an informative and thoughtful article by Teresa Castro, ‘Les Archives de la Planète: A cinematographic atlas’, which is a good place to start, and has some beautiful Autochrome illustrations.

There is no Les Archives de la Planète or Albert Kahn website with a collection of the images on show (update: the BBC has now created www.albertkahn.co.uk). The Hauts-de-Seine.net site has some pages on the Musée Albert Kahn giving basic information and access details, in French. [Another update: the link is now www.albert-kahn.fr]

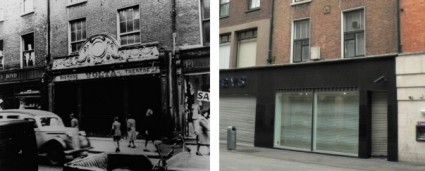

The Museum is located in the Paris suburb of Boulogne-Billancourt, and is renowned for its beautiful gardens. There is a plain official web page describing these, but you are better off reading the evocative New York Times article, ‘Philosophy in Bloom’, by Jacqueline McGrath, which describes a visit to the gardens (which are apparently not to easy to find).

Autochrome of French troops during First World War, from http://www.worldwaronecolorphotos.com

If you are entranced by Autochromes, there are several good sites to visit. This year (2007) sees the centenary of the Autochrome, recognised by www.autochrome.com [link now dead]. The highly recommended Luminous Lint photography site has an explanation of the ingenious Autochrome photographic process, involving the use of dyed potato starch grains acting as colour filters, which helped give them their particular ‘impressionist’ effect.

The site World War I Color Photos has some astonishing images from a conflict we generally only imagine in monochrome. Australian and French First World War Autochromes are reproduced on the Captured in Colour site (which also displays the Paget plate colour system). And there are more First World War Autochromes on the Heritage of the Great War site (though do note this site mixes these up with other coloured images, including artifically-coloured postcards).

The Library of Congress has a page on the restoration of Autochromes. There is an exhibition of the expressive Autochrome work of Gabriel Veyre at www.gabrielveyre-collection.org (Veyre did not work for Kahn but was previously a film cameraman with the Lumière brothers, inventors of the Autochrome). George Eastman House has an online exhibit of eighty Autochromes from the Charles Zoller collection, reproduced in high resolution. The Galerie-Photo site has an exhibition of Autochromes (originally stereoscopic i.e. 3D), with some interesting technical observations.

American academic Paula Amad has written “Cinema’s ‘sanctuary’: From pre-documentary to documentary film in Albert Kahn’s Archives de la Planète (1908-1931)” for the journal Film History, the best single source for information on Kahn’s project, and is writing a book on the collection.

The site www.autochrome.org [link now dead] doesn’t have that much information, but it does tell you in detail how to make your own Autochromes the original way (it’s not easy). If you don’t want to try the original potato starch method, why not use Photoshop? PhotoshopSupport.com will show you how.

Pioneering scientific filmmaker Dr Jean Comandon was one of those who worked for Kahn, late on in the project, as the Institut Pasteur explains (in French).

Definitely the book on Autochromes to buy is John Wood’s The Art of the Autochrome. There will be no more beautiful title on your bookshelves.

Lastly, look out for the National Media Museum’s forthcoming exhibition The Dawn of Colour: Celebrating the Centenary of the Autochrome, which opens on May 25th.

Update (April 2008): The BBC has now produced an Albert Kahn website, www.albertkahn.co.uk, which has information on Kahn, the autochromes and the Albert Kahn museum, as well as promoting the new BBC book The Wonderful World of Albert Kahn: Colour Photographs from a Lost Age. No plans have been announced for a DVD release of the BBC series, presumably owing to licensing issues. However, the Kahn museum section of the new BBC site refers to some DVDs, without going into further details. It has been rumoured that the museum was planning to produce some DVDs of its own, showcasing its Autochrome colour photographs (and its films?). This may be a reference to these, which do not seem to have been published as yet.

Another update (March 2009): There are faint rumours of a possible DVD release, in some form. However, the original The Wonderful World of Albert Kahn series is now available on DVD from the BBC, but only from its educational service, BBC Active, where it is priced at an eye-watering £1,125 for 9x50mins DVDs – the intended market is institutions only. This existence (and price) of this would suggest that any subsequent commercial release to the public will be highlights in some form.

And another update (September 2009): There is now a proper website for the Musée Albert Kahn, at www.albert-kahn.fr. It’s all in French, but includes several examples of the autochromes, photographs of the museum and gardens, a biography of Kahn, and news of exhibitions etc.

Final (?) update (September 2009)

Good news – the BBC has brought out the series on DVD. The Wonderful World of Albert Kahn is a 3-disc set (PAL, region 2), divided into nine parts, running 462mins. It’s released by 2 entertain, which is part-owned by BBC Worldwide.