Scene outside the court room at Rennes, probably showing chief prosecution witness General Mercier on the left, from the Société Française de Mutoscope et Biographe Dreyfus trial scene film, courtesy of Filmmuseum, Amsterdam.

Part one of this series covered the early films of the Dreyfus affair made by Georges Méliès; part two completed the picture with the early films made by Biograph and Pathé. This final post supplies a plain filmography, for reference purposes. It includes a film by Lubin which was overlooked for the first two posts. It is arranged by film company. It does not include post-silent era productions.

American Mutoscope and Biograph Company

Dreyfus Receiving His Sentence (USA 1899)

Cast: Lafayette [Sigmund Neuberger] (Alfred Dreyfus)

68mm bw st ??ft

Archive: none

Impersonation. “Lafayette, the mimic, showing Capt. Dreyfus reading the verdict of the court-martial in his prison, and meeting with Madame Dreyfus. This picture is very dramatic, and true to the details of the actual scene.” (American Mutoscope and Biograph Company, Picture Catalogue, 1902)

Trial of Captain Dreyfus (USA 1899)

Cast: Lafayette [Sigmund Neuberger] (Alfred Dreyfus)

68mm bw st ??ft

Archive: none

Impersonation. “An impressive character impersonation by Lafayette, the great mimetic comedian. The scene is from the famous court-martial at Rennes, ending with the prisoner’s dramatic declaration, ‘I am innocent’.” (American Mutoscope and Biograph Company, Picture Catalogue, 1902)

British Mutoscope and Biograph Company

The Zola-Rochefort Duel (UK 1898)

ph. W.K.-L. Dickson

68mm bw st 45″ (30fps)

Archive: Filmmuseum (Amsterdam)

Dramatic sketch. “This is a replica of the famous duel with rapiers between Emile Zola, the novelist, and Henri Rochefort, the statesman. The duel takes place on the identical ground where the original fighting occurred, seconds and doctors being present as in the original combat. The picture gives a good idea of how a French affair of honor is conducted.” (American Mutoscope and Biograph Company, Picture Catalogue, 1902)

Amann, the Great Impersonator (UK c.1899)

Cast: Ludwig Amann (Emile Zola/Alfred Dreyfus)

68mm bw st 30″ (30fps)

Archive: BFI National Archive (London)

Impersonation. Quick-change artist Amann impersonates first Emile Zola and then Alfred Dreyfus.

[American Biograph at the Palace] (UK 1899)

68mm bw st 35″ (30fps)

Archive: Filmmuseum (Amsterdam)

Comic sketch/advertisement. A tramp and a billsticker come to blows while the latter puts up a notice saying ‘Have You Seen the Mutoscope’. There are several posters advertising the Palace Theatre and the Biograph/Mutoscope, two of which mention the Dreyfus films.

Lubin

The Trial of Captain Dreyfuss at Rennes, France (USA 1899)

p. Siegmund Lubin

35mm st bw ??ft

Archive: none

Listed in Library of Congress Motion Pictures Catalog 1894-1912, copyrighted 28 September 1899

Pathé Frères

L’affaire Dreyfus (France 1899)

Jean Liezer (Dreyfus)

35mm bw st 155m

Catalogue nos. 516-523

Archive: BFI National Archive (one, possibly two, episodes only of eight, Entrée au conseil de guerre and maybe Dreyfus dans sa cellule à Rennes)

Description: French descriptions taken from Pathé Frères 1897-1899 catalogue; English versions taken from The Era, 21 September 1899.

No. 516/515: Arrestation, aveux du colonel Henry (20m)

“M. Cavaignac, ministre de la guerre, discute avec son chef de cabinet. Il mande un planton et lui ordonne de faire introduire le colonel. Le ministre interroge l’inculpé et lui présente le faux; le colonel se trouble et nie l’authenticité de la note. Mais, confronté avec le général accusateur, le colonel fait ses aveux. Le ministre le fait arrêter.”

No. 517/516: Au mont Valérien: suicide du Colonel Henry (20m)

“Aspect de la cellule. On aperçoit le colonel très agité. Le prisonnier envoie son gardien porter un message. Pendant ce temps, un général lui rend visite, le prie d’espérer et se retire. Mais le colonel, découragé, saisit son rasoir et, d’un élan énergique, il se coupe la gorge et tombe inanimé sur le sol.”

No. 518/517: Dreyfus dans sa cellule à Rennes / Dreyfus in the Military Prison at Rennes (20m)

“Assis à côté de sa femme, il veut la convaincre de son innocence et la prie d’espérer. Embrassades et pleurs. Un capitaine de gendarmerie entre et prévient Mme Dreyfus que l’heure de sa visite est écoulée.Les époux s’embrassent et Dreyfus reconduit sa femme jusqu’à la porte. Entrent les deux défenseurs: Mes Demange et Labori. Dreyfus les fait asseoir; ils se mettent ensemble à compulser le dossier.” / “Showing the cell in the prison in which Dreyfus, the accused, is confined during the time of his wife’s daily visit. Embraces and tears. A sergeant enters to tell Madame Dreyfus her visiting time is up. The parting of husband and wife is most pathetic and emotional. Dreyfus conducts his wife to the door. The two counsels for the defence, Maîtres Demange and Labori, then enter. The latter with his usual smile on his face full of good nature. Dreyfus asks them to be seated, and the three examine some documents together connected with the case.”

No. 519/518: Entrée au conseil de guerre / Entering the Lycee, 6.0 am (20m)

“Dreyfus traverse la rue et entre au Conseil. Mes Demange et Labori suivent en causant avec animation. Viennent ensuite les officiers témoins: général Mercier et autres, puis le colonel Jouaust, président du Conseil.” / “Streets lined with soldiers with fixed bayonets. Dreyfus with the Captain of Gendarmerie, crosses the street and enters the Lycee. Maître Demange and Labori, who appear very excited, then enter, followed by Officer-witnesses, General Mercier and other well-known personages are easily recognisable. Then comes Colonel Jouaust, the President of the Court.”

No. 520/519: Audience au conseil de guerre / Court Martial at Rennes (20m)

“Les avocats se concertent. Le colonel Jouaust les avertit que la séance va commencer: la cour entre, on introduit l’accusé. Le président donne la parole au général Mercier qui dépose.” / “A scene at the Lycee at Rennes, showing the military Court Matial of Captain Dreyfus. The only occupants of the room at this time are maîtres Demange and Labori, who are holding an animated conversation. The judges begin to arrive, and take their seats, Colonel Jouaust declares the court open, and orders the Sergeant to bring in the accused. Dreyfus enters, saluting the court, followed by the Captain of Gendarmerie, who is constantly with him. They take their appointed seats in front of the judges. Colonel Jouaust asks Adjutant Coupols to call the first witness, and General Mercier arives, and proceeds with his deposition. The scene which is a most faithful portrayal of the Court-Martial at Rennes, shows the absolute portraits of the principal personaes in the famous trial.”

No. 521/520: Sortie du conseil de guerre / Leaving the Lycee (20m)

“Officiers témoins, général Mercier en tête. Puis Dreyfus, accompagné d’un capitaine de gendarmerie. Viennent ensuite Mes Demange et Labori.” / “After the sitting witnesses go out, General Mercier first, followed by a number of others. Then Dreyfus, accompanied by Captain of Gendarmerie. Then Counsels for the Defence, Maîtres Demange and Labori, who seem pleased with their morning’s labours, and glad of the fresh air.”

No. 522: Prison militaire de Rennes, rue Duhamel (20m)

“Arrivée de l’officier d’infanterie assistant à l’entrevue dans la cellule. Arrivée de Mme Havet, tante de Mme Dreyfus et de M, son père. Sortie de Mme Dreyfus; Mme Havet et M l’accompagnent. Sortie de l’officier.”

No. 523: Avenue de la Gare à Rennes (15m)

“Sortie de Dreyfus du lycée. Aussitôt le barrage fermé, deux gendarmes sortent du lycée en traversant l’avenue pour aller ouvrir la porte de la manutention. Vient ensuite Dreyfus, suivi du capitaine de gendarmerie préposé à sa garde.”

L’affaire Dreyfus (France 1908)

d. Lucien Nonguet

p. Ferdinand Zecca

35mm bw st 370m

Catalogue no. 2237

Archive: Archives du Film (?)

Description: “L’Affaire Dreyfus – Cette intéressante vue nous donne une vivante idée des principaux incidents de l’affaire Dreyfus qui troubla si violemment les milieux militaires français en 1894. Alfred-Henri Dreyfus, officier au Ministère de la Guerre, était accusé d’avoir vendu des secrets militaires à une puissance étrangère. Il fut jugé et reconnu coupable, d’après des preuves insuffisantes, puis condamné à la détention à l’île du Diable où il resta huit ans. Jusqu’au moment où l’influence de ses partisans démontra qu’il était victime d’un complot . Finalement, il fut gracié par le président Loubet et reprit sa place dans l’armée. Dans la première scène, on voit Estherazy s’emparer d’un papier sur le bureau d’Henry pour l’envoyer à Swartzkoppen. Henry le voit le prendre, mais n’en laisse rien savoir, parce que c’est lui qui a forgé le document et l’a mis juste à l’endroit où on pouvait s’en emparer. Un garçon du baron découvrit le document sur son bureau et le fit tenir au Ministre de la Guerre – qui soupçonne Dreyfus. Il fait venir ce dernier et le prie de signer son nom. Cela fait, il compare l’écriture avec celle du document et accuse Dreyfus de trahison. Il appelle des agents de la sûreté et Dreyfus est arrêté. Nous le voyons ensuite dans sa cellule où vient le voir sa fidèle femme convaincue de son innocence. Il est traîné devant le conseil de guerre et, après un rapide procès, condamné à une terrible sentence. Alors, il est dégradé en place publique et voit son sabre brisé sur le genou d’un officier, son supérieur. On l’emmène en prison, marqué comme un traître, et c’est une pathétique scène que celle de son départ pour l’île du Diable. On le voit dans sa solitude, alors qu’il passe son temps à regarder l’horizon, rêvant de sa famille dans la patrie lointaine. Enfin, après des années de souffrance, pendant lesquelles ses amis luttèrent pour sa justification, Henry avoue son faux et se suicide. L’heureuse nouvelle de la grâce arrive au prisonnier dans sa case et nous le voyons rentrer en France où il est replacé dans le grade qu’il avait précédemment dans l’armée” Et voilà justement comme on écrit l’histoire au cinématographe-monopole ! Ne croirait-on pas voir quelque vieille image d’Épinal dont se réjouissait notre enfance ? Un tel document au lieu de relever la faveur du cinéma est de nature à l’abaisser … mais quoi ? tout le monde n’est pas Michelet !” [This is a French translation of part of a review in Moving Picture World, 4 July 1908, reproduced at http://filmographie.fondation-jeromeseydoux-pathe.com]

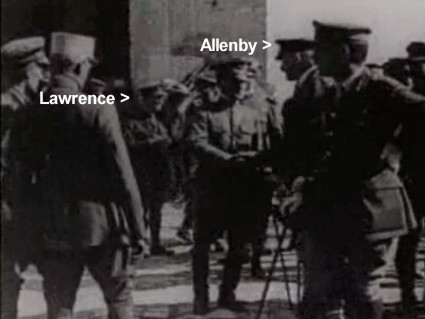

Société Française de Mutoscope et Biographe

[Dreyfus Trial Scenes] (France 1899)

68mm bw st c.4mins (30fps)

Archive: Filmmuseum (Amsterdam)

Actuality. Several scenes filmed at Rennes during the time of the Dreyfus re-trial, including fleeting views of Dreyfus himself and several of the major participants in the drama.

[Trial scene 1]

Scenes at Rennes in front of Lycée court building. Carrying out evidence in a basket? Various presumably notable figures exit the main gates.

[Trial scene 2]

Carriage arrives outside the Lycée for woman, presumably Lucie Dreyfus. Large gathering of military officers.

[Trial scene 3]

Guards on foot and on horseback lined up outside Lycée with their backs to a figure who comes out of the building (presumably Dreyfus) and passes by (view obscured) to left, with rapid panning shot.

[Trial scene 4]

Possibly General Mercier standing by the main gate to the Elysée. Dreyfus’ lawyer Fernand Labori may be in this scene as there are reports of British audiences cheering Labori and booing Mercier.

[Trial scene 5]

Large crowd (probably journalists) coming out of a doorway during the trial, some of whom recognise the camera.

Dreyfus in Prison

View from above of the prison courtyard showing Dreyfus and an accompanying officer walking out of one door and in through another. Sequence repeated. Title from London Palace Theatre of Varieties programme, 21 August 1899.

Madam Dreyfus Leaving the Prison

Lucie Dreyfus and her brother-in-law Mathieu Dreyfus walking along street, with panning shot. Title from London Palace Theatre of Varieties programme, 21 August 1899.

Dreyfus Walking from the Lycée to the Prison

Figures leave court room including Dreyfus (only half-visible) past the guards on foot and on horseback all with their backs turned. Dreyfus followed as he passes to the left by panning shot. Guards then disperse. Title from Manchester Palace Theatre of Varieties programme, 4 December 1899.

Star-Film

L’affaire Dreyfus (France 1899)

d. Georges Méliès

Cast: Georges Méliès (Fernand Labori)

35mm bw st 240m c.15mins

Catalogue nos. 206-217

Archive: BFI National Archive (London) [nine episodes from original eleven; nos. 216 and 217 are missing]

Descriptions taken from the Warwick Trading Company catalogue (November 1899):

No. 206: La dictée du bordereau / Arrest of Dreyfus, 1894 (20m)

“Du Paty de Clam requests Captain Dreyfus to write as he dictates for the purpose of ascertaining whether his handwriting conforms to that of the Bordereau. He notices the nervousness of Dreyfus, and accuses him of being the author of the Bordereau. Paty du Clam offers Dreyfus a revolver, with advice to commit suicide. The revolver is scornfully rejected, Dreyfus stating that he had no need for such cowardly methods, proclaiming his innocence.”

No. 216: La dégradation / The Degredation of Dreyfus in 1894 (20m)

[note that the catalogue number is not correct in terms of historical chronology]

“Shows the troops ranging in a quadrant inside the yard of the Military School in Paris. The Adjutant, who conducts the degredation, reads the sentence and proceeds to tear off in succession all of the buttons, laces, and ornaments from the uniform of Captain Dreyfus, who is compelled to pass in disgrace before the troops. A most visual representation of this first act of injustice to Dreyfus.”

No. 207: L’Ile du diable / Dreyfus at Devil’s Island – Within the Palisade (20m)

“The scene opens within the Palisades, showing Dreyfus seated on a block meditating. The guard enters bearing a letter from his wife, which he hands to Captain Dreyfus. The latter reads it and endeavours to talk to the Guard, who, however, refuses to reply, according to strict orders from his Government, causing Dreyfus to become very despondent.”

No. 208: Mise aux fers de Dreyfus / Dreyfus Put in Irons – Inside Cell at Devil’s Island (20m)

“Showing the interior view of the hut in which Dreyfus is confined. Two guards stealthily approach the cot upon which Dreyfus is sleeping. They awake him and read to him the order from the French minister – M. Lebon – to put him into irons, which they proceed at once to accomplish. Dreyfus vigorously protests against this treatment, which protests, however, fall on deaf ears. The chief sergeant and guards before leaving the hut, inspect the four corners of same by means of a lantern.”

No. 209: Suicide du Colonel Henry / Suicide of Colonel Henry (20m)

“Shows the interior of the cell of the Prison Militaire du Cherche-Midi, Paris, where Colonel Henry is confined. He is seated at a table writing a letter on completion of which he rises and takes a razor out he had concealed in his porte-manteau, with which he cuts his throat. The suicide is discovered by the sergeant of the guard and officers.”

No. 210: Débarquement à Quiberon / Landing of Dreyfus from Devil’s Island (20m)

“A section of the port Quiberon, Bretagne, at night where Dreyfus was landed by French marines, and officers after his transport from Devil’s Island. He is received by the French authorities, officers, and gendarmes, and conducted to the station for his departure to Rennes. This little scene was enacted on a dark rainy night, which is clearly shown in the film. The effects are further heightened by vivid flashes of lightning which are certainly new in cinematography.”

No. 211: Entrevue de Dreyfus et de sa femme à Rennes / Dreyfus in Prison of Rennes (20m)

“Showing room at the military prison at Rennes in which Dreyfus the accused is confined. He is visited by his counsel, Maître Labori and Demange, with whom he is seen in animated conversation. A visit from his wife is announced, who enters. The meeting of the husband and wife is most pathetic and emotional.”

No. 212: Attentat contre Me Labori / The Attempt Against Maître Labori (20m)

“Maître Labori is seen approaching the bridge of Rennes in company with Colonel Picquart and M. Gast, Mayor of Rennes. They notice that they are followed by another man to whom Colonel Picquart calls Labori’s attention. They, however, consider his proximity of no importance, and continue to speak together. As soon as their backs are turned, the man draws a revolver and fires twice at Maître Labori, who is seen to fall to the ground. The culprit makes his escape, pursued by Colonel Picquart and M. Gast.”

No. 213: Bagarre entre journalistes / The Fight of the Journalists at the Lycée (20m)

“During an interval in the proceedings of the court martial, the journalists enter into an animated discussion, resulting in a dispute between Arthur Myer of the `Gaulois’, and Mme Severine of the `Fonde’, resulting in a fight between Dreyfusards and Anti-Dreyfusards, in which canes and chairs are brought down upon the heads of many. The room is finally cleared by the gendarmes.”

Nos: 214-15: Le conseil de guerre en séance à Rennes / The Court Martial at Rennes (40m)

“A scene in the Lycée at Rennes, showing the military court-martial of Captain Dreyfus. The only occupants of the room at this time are Maître Demange and secretary. Other advocates and the stenographers now begin to arrive and the sergeant is seen announcing the arrival of Colonel Jouaust and other officers comprising the seven judges of the court-martial. The five duty judges are also seen in the background. On the left of the picture are seen Commander Cordier and Adjutant Coupois, with their stenographers and gendarmes. On the right are seen Maître Demange, Labori, and their secretaries. Colonel Jouaust orders the Sergeant of the Police to bring in Dreyfus. Dreyfus enters, saluting the court, followed by the Captain of the Gendarmerie, who is constantly with him. They take their appointed seats in front of the judges. Colonel Jouaust puts several questions to Dreyfus, to which he replies in a standing position. He then asks Adjutant Coupois to call the first witness, and General Mercier arrives. He states that his deposition is a lengthy one, and requests a chair, which is passed to him by a gendarme. In a sitting position he proceeds with his deposition. Animated discussion and cross-questioning is exchanged between Colonel Jouaust, General Mercier, and Maître Demange. Captain Dreyfus much excited gets up and vigorously protests against these proceedings. This scene, which is a most faithful portrayal of this proceeding, shows the absolute portraits of over thirty of the principal personages in this famous trial.”

No. 217: Dreyfus allant du lycée à la prison / Officers and Dreyfus Leaving the Lycee (20m)

“The exterior of the Lycee de Rennes, where the famous Dreyfus Court-Martial was conducted, showing hte French staff leaving the building after the sitting, and crossing the yard between the French soldiers forming a double line. Maîtres Demange and Labori also make their appearance, walking towards the foreground of the picture, and at length Captain Dreyfus is seen approaching, being accompanied by the Captain of Gendarmes, who is conducting him back to prison.”